Aftermath (2012 film)

Aftermath (Polish: Pokłosie) is a 2012 Polish film written and directed by Władysław Pasikowski. The fictional Holocaust-related thriller and drama is inspired by the July 1941 Jedwabne pogrom in occupied north-eastern Poland during Operation Barbarossa, in which 340 Polish Jews of Jedwabne were locked in a barn later set on fire by a group of Polish males who were motivated by antisemitism.[1][2]

| Aftermath | |

|---|---|

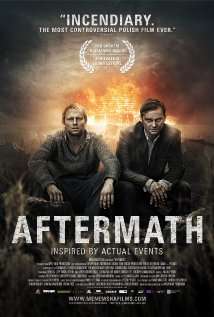

English-language film poster for U.S. theatrical release | |

| Directed by | Wladyslaw Pasikowski |

| Distributed by | Menemsha Films and Monolith Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

Plot

The film is a contemporary drama.[3] It takes place in the fictional village of Gurówka in 2001. The story begins with the return of Franciszek Kalina (Ireneusz Czop) to his hometown in rural Poland after having lived in Chicago for two decades. He learns that his brother Józef (Maciej Stuhr) is shunned by the community for acquiring and displaying on his farmland dozens of Jewish tombstones which he discovered had been used by German occupying forces as paving stones in a now abandoned road.[4] Józef is gathering the tombstones everywhere in the settlement and moves them into his own field to survive from oblivion. Against the growing opposition of the town residents, the Kalina brothers attempt to learn more about what happened to the Jews of the village. Their personal relationship, harsh after the brothers met, warms and becomes more cooperative after they both find themselves opposed by the whole village. The older priest blesses the brother and urges him to continue gathering the tombstones while the new one, to head the parish soon, displays no sympathy for Jews. Franciszek discovers in a local archive that his father along with other men of the village got the land that had been owned by Jews before the war. He is eager to study the truth.

After speaking to some of the oldest residents in the village, the brothers subsequently realize that half the residents of the village murdered the other half [5] (led by a neighbor and their father Stanisław Kalina). This discovery results in a terrible fight and split between the brothers after a dispute about the bones of the Jews they found the night before. After learning that their own father was directly involved in the murder of the Jews who were burned to death in the family's former house, the brothers' roles are reversed. Now it is Józef who wants to keep the truth from coming out to the world, while Franciszek wants the world to know the truth and for the bones of the murdered Jews to be taken to their wheat field and buried with their headstones, so as to not compound the terrible sins of their father and neighbors. In a fight, Franciszek comes close to killing his brother Józef but Franciszek stops himself, puts the ax down and leaves the village by bus to go back to America. But he is returned to the village by a hospital nurse/doctor—the daughter of one of the oldest surviving neighbors who had known the truth but kept it secret—only to see his brother Józef beaten, stabbed, and then nailed high on the inside of the barn door, his arms outstretched. His wrists and feet held by wooden cleats.

The movie ends with a scene of a group of young and older Israeli Jews being led by an Orthodox Rabbi reciting the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer in memory of the dead, in front of a formal memorial stone, at the now restored cemetery in the area of the stones that Józef had placed in his fields, while Franciszek watches with respect, lights a candle, leaves it on one of the tombstones and nodding slightly to the scene, turns and walks away.

Cast

- Ireneusz Czop as Franciszek Kalina

- Maciej Stuhr as Józef Kalina, brother of Franciszek

- Jerzy Radziwiłowicz as the rector

- Zuzana Fialová as Justyna, granddaughter of Sudecki

- Andrzej Mastalerz as Janusz Pawlak

- Zbigniew Zamachowski as police sgt. Włodzimierz Nowak

- Danuta Szaflarska as the elderly herbalist

Production notes

The inspiration for Pasikowski to write and direct the film, which was originally titled Kaddish (the Jewish prayer read by those in mourning),[6][7] was the controversy in Poland surrounding the 2000 publication of Neighbors by Polish-American historian Jan T. Gross. According to Gross's historical research into the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom, Polish gentiles had murdered the hundreds of Jewish residents of Jedwabne, contrary to the official history which held the Nazi occupying force accountable. Gross's account of the Jedwabne massacre was a jarring development for Poles, "accustomed to seeing themselves as victims during World War II", rather than the victimizers.[8]

Nationalists opposed to these findings accused Gross of anti-Polish slander and misrepresenting the historical truth. At the same time though, it inspired among Poles "a new curiosity in Polish Jewish history", including for Pasikowski.[6] Pasikowski stated, "The film isn't an adaptation of the book, which is documented and factual, but the film did grow out of it, since it was the source of my knowledge and shame."[8]

Over the course of about a decade, Pasikowski struggled to have the film produced. He encountered difficulties "securing financing for his controversial script" and "struggling with how to best approach what is, for many Poles, still a largely taboo subject".[6] Ultimately, it took seven years for producer Dariusz Jabłoński to receive backing from the state film fund for Aftermath.[8]

Aftermath was the first feature film produced by Pasikowski in a decade.[3]

Reception

Poland

In Poland, the film reignited the controversy about the nature of the Jedwabne massacre, which began with the publication of Gross's Neighbors. The film was praised by government officials and leading cultural figures, including culture minister Bogdan Zdrojewski, filmmaker Andrzej Wajda, and Polish film historian Malgorzata Pakier.[8]

Conversely, many of typical spectators were infuriated. The movie was condemned by "nationalist politicians, banned in some towns and excoriated on the Internet". The right-wing newspaper Gazeta Polska described the film as "mendacious and harmful for Poles". Wprost, one of Poland's largest weekly, ran a cover with Stuhr's image framed in a Jewish star, accompanied by the headline, "Maciej Stuhr—Was He Lynched at His Own Request?"[8][9]

Worldwide

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported a 79% approval rating with an average rating of 7.2/10 based on 29 reviews.[10] As of April 2, 2014, Metacritic gives the film a weighted average score of 62/100, based on 12 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews", with no user reviews at this time.[11]

Accolades

Aftermath has won a few awards, including the Yad Vashem Chairman's Award at the Jerusalem Film Festival in 2013,[12] Jan Karski Eagle Award in 2013,[13] and Winner — Critics Prize, Gdynia Film Festival 2012. It won two Polish Film Awards, Best Actor — Maciej Stuhr and Best Production Design — Allan Starski in 2013.[14]

See also

References

- P.A.I.C., The Jedwabne Tragedy. Polish Academic Information Center, University of Buffalo, 2000, via Internet Archive.

- Public Prosecutor Radosław J. Ignatiew (July 9th , 2002), Jedwabne: Final Findings of Poland's Institute of National Memory. Communiqué. Polish Academic Information Center, University of Buffalo. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- czapi (27 September 2012). "'Pokłosie': zobacz zwiastun tylko u nas" ['Aftermath': see the trailer only with us] (in Polish). Onet.pl. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Fine, Marshall (2013-10-28). "Movie Review: Aftermath". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- Abramovitch, Seth (October 28, 2013). "'Aftermath' Dares to Unearth Terrible Secrets of Poland's Lost Jews". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- Grollmus, Denise (17 April 2013). "In the Polish Aftermath". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- A.H. (5 January 2013). "Poland's past: A difficult film". The Economist. Eastern Approaches (blog). Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Hoberman, J. (25 October 2013). "The Past Can Hold a Horrible Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Rigamonti, Magdalena (2012-11-19). "Czy Maciej Stuhr został zlinczowany na własną prośbę?". Wprost (in Polish). Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- "Aftermath (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- "Aftermath". Metacritic. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- Jones Jeromski, Mai (2013-07-15). "Jewish Award for Film on Polish Secrets". Culture.pl. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- "Aftermath". San Francisco Jewish Film Festival. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- Grynienko, Katarzyna (25 November 2013). "Aftermath scores international sales". FilmNewEurope.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2014.