Adelperga

Adelperga (born c. 740 – died after 787) was a Lombard noblewoman. She was the third of four daughters of Desiderius, King of the Lombards, and his wife Ansa.[1][2] Her elder sister Desiderata was a wife of Charlemagne.

Adelperga | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 740 |

| Died | after 787 |

| Spouse(s) | Arechis II of Benevento |

| Children | Grimoald III of Benevento |

| Parent(s) | Desiderius Ansa, Queen of the Lombards |

Family

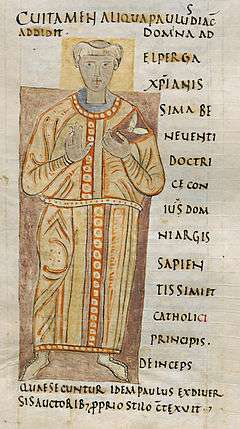

Adelperga was tutored by Paul the Deacon. In c. 757, she married Arechis II, Duke of Benevento. She remained in contact with Paulus, who at her request wrote his continuation of Eutropius in c. 775.[3] Paul dedicated to her his Versus de Annis, an acrostic spelling Adelperga pia.[4]

Adelperga and Arechis had five children,[5] Romuald (761/2–787), Grimoald (before 773 – April 806), Gisulf (d. before 806), Theoderada (d. after 787) and Adelchisa (b. after 773, d. after 817), abbess of San Salvatore d'Alife.

Charlemagne

After the fall of the Kingdom of the Lombards to Charlemagne, Adelperga's parents and sister were exiled to Francia, where they were imprisoned in religious houses.

Adelperga and her sister Liutperga embarked upon a struggle to regain their patrimony and take revenge upon Charlemagne. Liutperga ultimately brought ruin upon herself and her family by encouraging her husband Tassilo to rebel against his cousin Charlemagne. Charlemagne discovered Tassilo's plots and confiscated his goods. Tassilo, Liutperga and their children were banished to monasteries.

Adelperga was more successful; her husband resisted Charlemagne for some time, until in 787 he agreed to make peace. At the encouragement of his wife and the Byzantines, he refused the peace treaty, which would have entailed surrendering part of his duchy to the Papacy.[6]

Adelperga and Arechis sponsored the church of Santa Sofia in Benevento.

When Arechis died on 26 August 787, Adelperga acted as regent, because Charlemagne hesitated to release Adeleperga's son Grimoald, whom he kept as a hostage. Grimoald was released and acceded as duke in February 787. Grimoald swore fealty to Charlemagne and defeated a Byzantine invasion commanded by Adelchis. After this, Adelperga is not again mentioned.[7]

References

- Reardon, Wendy J. The Deaths of the Popes. Comprehensive Accounts Including Funerals, Burial Places and Epitaphs. McFarland. p. 59.

- Ghisalberti, Alberto M. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani: III Ammirato – Arcoleo. Rome, 1961.

- Paulus had sent Adelperga his copy of Eutropius in 774, but she complained the absence of any treatment of the history of Christianity, so Paulus wrote his continuation, writing additions of the kind she requested as well as extending the account from the time of Valens to that of Justitianus. Max Manitius, Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur des Mittelalters, C.H.Beck, 1974, p. 257.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Poetae Latini aevi Carolini 1 (1881), 35f.

- Italy, Emperors & Kings

- Noble, T. F. X. (1984). The Republic of St. Peter: the Birth of the Papal State, 680–825. Philadelphia.

- King, P. D. (1987): Charlemagne: Translated Sources