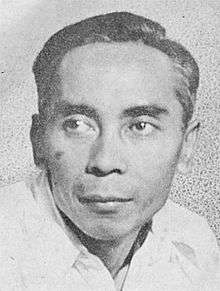

Achdiat Karta Mihardja

Achdiat Karta Mihardja (March 6, 1911 – July 8, 2010) was an Indonesian author, novelist and playwright. He is best known for his novel, Atheis, which was published in 1949. Atheis is considered one of Indonesia's most important literary works following World War II.[1]

Biography

Mihardja was born on March 6, 1911, in Garut, West Java. His father, a bank manager, had a collection of books which Mihardja credited with sparking his interest in literature.[1] He worked as a journalist early in his career. In 1949, he published his most important work, Atheist, which centered on a Muslim man from West Java, Hasan, and his relationship with his friends, who had been influenced by foreign ideas, such as Marxism.[2] The book is considered as one of Indonesia's most important modern literary works.[3] Atheist was later adapted into a 1974 film, which was directed by Sjumandjaja and co-starred Christine Hakim and Deddy Sutomo. Mihardja was a recipient on Indonesia's national literary award in 1956 for his work.[1]

In 1950, he helped to found Lekra, an Indonesian writers' organization tied to the Communist Party of Indonesia. He was also a major figure in PEN Club Indonesia during the mid-1950s, seeking international connections with such figures as English poet Stephen Spender and helping to host African American novelist Richard Wright during his visit to Indonesia for the 1955 Bandung Conference.[4] Though rumors persisted, he denied that he, himself, was an atheist. He was a member of the Socialist Party of Indonesia, which was banned in 1960 by his friend, President Sukarno. He would later speak about his relationship with Sukarno: "We were best friends but not in terms of ideology...Worse, out of the blue he banned my party."[1]

In 1961, he became a professor of Indonesian literature and language at Australian National University, on invitation from the university. He ultimately chose to settle in Canberra in Australia in the 1960s where he lived for more than 40 years. However, he continued to receive recognitions for his work in Indonesia. He was presented with Indonesia's arts award in 1971.[1]

His last visit to Indonesia was in June 2005. The visit was to promote the release of Manifesto Khalifatullah, a follow-up novel to Atheist which went on sale on June 7, 2005. He described the novel as his answer to issues raised in Atheist and its main message to be that "God made man to be His representative on earth, not that of Satan." In 2009 he expressed an interest in writing his autobiography, but he was unable to complete this work.[1]

He suffered a stroke in July 2010 and died of complications in Canberra on July 8, 2010 at the age of 99. He was survived by his wife, Tati Suprapti Noor, and four children. He was buried in Canberra on the same day.[1]

The actor and singer, Jamie Aditya, is his grandson.

References

- "Obituary: 'Atheist' writer laid to rest in Canberra". Jakarta Post. 2010-07-09. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- The manuscript can be found in the H.B. Jassin Library of Indonesian literature at Taman Ismail Marzuki cultural centre in central Jakarta. See Desi Anwar, 'Desi Anwar: Lost for Words', The Jakarta Globe, 1 September 2012.

- The story of the book, and some details of the film that was based on it, are at Olin Monteiro, 'Rethinking Atheism Through an Indonesian Filmmaker's Lens', The Jakarta Globe, 27 March 2012.

- Roberts and Foulcher (2016). Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference. Duke University Press. p. 18.