Acetabularia acetabulum

Acetabularia acetabulum is a species of green alga in the family Polyphysaceae. It is found in the Mediterranean Sea at a depth of one to two metres.[2]

| Acetabularia acetabulum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Top view of caps of Acetabularia acetabulum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Phylum: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Ulvophyceae |

| Order: | Dasycladales |

| Family: | Polyphysaceae |

| Genus: | Acetabularia |

| Species: | A. acetabulum |

| Binomial name | |

| Acetabularia acetabulum (Linnaeus) P. C. Silva, 1952 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Acetabularia integra J. V. Lamouroux | |

Description

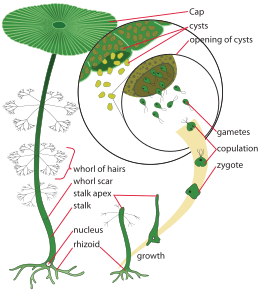

This alga adheres to the substrate with rhizoids (root-like processes), and these are the only part of the alga present in the winter. The thallus consists of a single cell, and in the spring a slender stem develops from the holdfast, growing vertically to a length of about 5 cm (2 in). Growth is interrupted at intervals while a whorl of hairs develop which encircle the stem, branching dichotomously. As the stem lengthens and more whorls grow, the lower hairs drop off leaving behind a circular scar. When the stem is fully developed, a disc-shaped cap up to 1.2 cm (0.5 in) wide grows at the tip, the whole frond resembling a pale green parasol; further whorls of hairs grow from the upper surface of the cap.[3][4]

Biology

Before cap expansion, the organism consists of a single cell with a single nucleus, located at the base of the stem.[3] As the cap expands, the nucleus divides once by meiosis after which it divides multiple times by mitosis, producing thousands of haploid "secondary" nuclei. These migrate up the stem into the cap, each becoming enclosed in a gametangium containing the nucleus and a small amount of cytoplasm. Inside the gametangium, the nucleus undergoes further repeated mitotic division, so that by the end of summer, when the cap disintegrates, thousands of "tertiary" nuclei are released into the sea as gametes from each gametangial ray. Fertilisation occurs in the open water, and the zygotes settle on the seabed.[3]

This alga is unicellular, each frond being formed from a single large cell containing several million chloroplasts.[5] These are in constant motion: in the daytime, they move to expose to themselves to the maximum degree possible to the light and the stems appear uniformly dark green, while at night they aggregate into clusters and the stem becomes pale green. This effect can be demonstrated by shining a ray of blue light on a stem in the dark and extinguishing it some time later, forming a transient green band.[5]

This alga has been used as a model organism in developmental biology, being useful for this purpose because of the enormous size of its single cell with its single nucleus, and its complex cytoarchitecture and development.[3]

The main storage polysaccharide of Acetabularia acetabulum is starch as granules within the chloroplast's stroma.[2]

Predators of Acetabularia acetabulum include the sea slug Elysia timida.[2]

References

- Guiry, Michael D. (2015). Acetabularia acetabulum (Linnaeus) P.C.Silva, 1952. In: Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. (2017). AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway (taxonomic information republished from AlgaeBase with permission of M.D. Guiry). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=494795 on 2017-05-06

- Laetz, E.M.J.; Moris, V.C.; Moritz L.; Haubrich, A.N.; Wägele, H. (2017). "Photosynthate accumulation in solar-powered sea slugs - starving slugs survive due to accumulated starch reserves". Frontiers in Zoology 14: 4. doi:10.1186/s12983-016-0186-5.

- International Review of Cytology: A Survey of Cell Biology. Academic Press. 1998. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-08-085721-3.

- "Acétabulaire: Acetabularia acetabulum (Linnaeus) Silva" (in French). DORIS. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Sybesma, C. (2013). Advances in Photosynthesis Research: Proceedings of the VIth International Congress on Photosynthesis, Brussels, Belgium, August 1–6, 1983. Springer. p. 884. ISBN 978-94-017-4971-8.

External links