Body cavity

A body cavity is any space or compartment, or potential space in the animal body. Cavities accommodate organs and other structures; cavities as potential spaces contain fluid.

| Body cavity | |

|---|---|

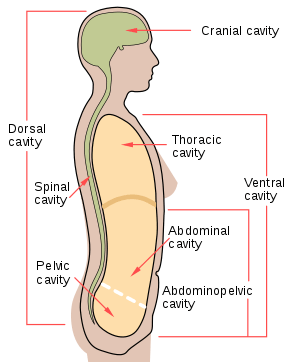

Cross-section showing cavities in the human body, the dorsal and ventral body cavities labelled. | |

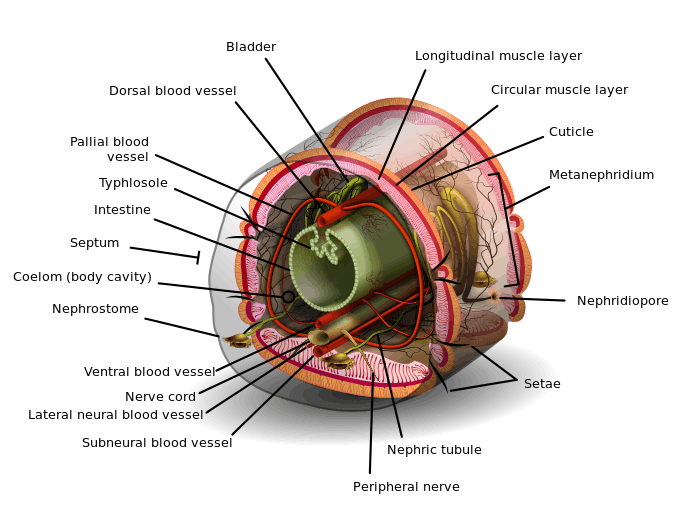

Cross-section of an oligochaete worm. The worm's body cavity surrounds the central typhlosole. | |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 85006 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The two largest human body cavities are the ventral body cavity, and the dorsal body cavity. In the dorsal body cavity the brain and spinal cord are located.

The membranes that surround the central nervous system organs (the brain and the spinal cord, in the cranial and spinal cavities are the three meninges. The differently lined spaces contain different types of fluid. In the meninges for example the fluid is cerebrospinal fluid; in the abdominal cavity the fluid contained in the peritoneum is a serous fluid.

In amniotes and some invertebrates the peritoneum lines their largest body cavity called the coelom.

Mammals

Mammalian embryos develop two cavities: the intraembryonic coelom and the extraembryonic coelom (or chorionic cavity). The intraembryonic coelom is lined by somatic and splanchnic lateral plate mesoderm, while the extraembryonic coelom is lined by extraembryonic mesoderm. The intraembryonic coelom is the only cavity that persists in the mammal at term, which is why its name is often contracted to simply coelomic cavity. Subdividing the coelomic cavity into compartments, for example, the pericardial cavity / pericardium, where the heart develops, simplifies discussion of the anatomies of complex animals.

Human body cavities

The dorsal (posterior) cavity and the ventral (anterior) cavity are the largest body compartments.

The dorsal body cavity includes the cranial cavity, enclosed by the skull and contains the brain, and the spinal cavity, enclosed by the spine and contains the spinal cord[1] The ventral body cavity includes the thoracic cavity, enclosed by the ribcage and contains the lungs and heart; and the abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity can be divided into the abdominal cavity, enclosed by the ribcage and pelvis and contains the kidneys, ureters, stomach, intestines, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas; and the pelvic cavity, enclosed by the pelvis and contains bladder, anus and reproductive system.[1]

| Human body cavities and membranes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of cavity | Principal contents | Membranous lining | ||

| Dorsal body cavity | Cranial cavity | Brain | Meninges | |

| Vertebral canal | Spinal cord | Meninges | ||

| Ventral body cavity | Thoracic cavity | Heart, Lungs | Pericardium Pleural cavity | |

| Abdominopelvic cavity | Abdominal cavity | Digestive organs, spleen, kidneys | Peritoneum | |

| Pelvic cavity | Bladder, reproductive organs | Peritoneum | ||

Ventral body cavity

The thoracic cavity consists of three cavities that fill the interior area of the chest.

- The two pleural cavities are situated on both sides of the body, anterior to the spine and lateral to the breastbone.

- The superior mediastinum is a wedge-shaped cavity located between the superior regions of the two thoracic cavities.

- The pericardial cavity within the mediastinum is located at the center of the chest below the superior mediastinum. The pericardial cavity roughly outlines the shape of the heart.

The diaphragm divides the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. The abdominal cavity occupies the entire lower half of the trunk, anterior to the spine. Just under the abdominal cavity, anterior to the buttocks, is the pelvic cavity. The pelvic cavity is funnel shaped and is located inferior and anterior to the abdominal cavity. Together the abdominal and pelvic cavity can be referred to as the abdominopelvic cavity while the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic cavities together can be referred to as the ventral body cavity.[2] Subdivisions of the Posterior (Dorsal) and Anterior (Ventral) Cavities The anterior (ventral) cavity has two main subdivisions: the thoracic cavity and the abdominopelvic cavity. The thoracic cavity is the more superior subdivision of the anterior cavity, and it is enclosed by the rib cage. The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum. The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest cavity in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, the division that houses the digestive organs, and the pelvic cavity, the division that houses the organs of reproduction.[2]

Dorsal body cavity

- The cranial cavity is a large, bean-shaped cavity filling most of the upper skull where the brain is located.

- The spinal cavity is a very narrow, thread-like cavity running from the cranial cavity down the entire length of the spinal cord.

Together the cranial cavity and spinal (or vertebral) cavity can be referred to as the dorsal body cavity. In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain, and the spinal cavity encloses the spinal cord. Just as the brain and spinal cord make up a continuous, uninterrupted structure, the cranial and spinal cavities that house them are also continuous. The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and vertebral column and by cerebrospinal fluid, a colorless fluid produced by the brain, which cushions the brain and spinal cord within the posterior (dorsal) cavity.[2]

Development

At the end of the third week, the neural tube, which is a fold of one of the layers of the trilaminar germ disc, called the ectoderm, appears. This layer elevates and closes dorsally, while the gut tube rolls up and closes ventrally to create a “tube on top of a tube.” The mesoderm, which is another layer of the trilaminar germ disc, holds the tubes together and the lateral plate mesoderm, the middle layer of the germ disc, splits to form a visceral layer associated with the gut and a parietal layer, which along with the overlying ectoderm, forms the lateral body wall. The space between the visceral and parietal layers of lateral plate mesoderm is the primitive body cavity. When the lateral body wall folds, it moves ventrally and fuses at the midline. The body cavity closes, except in the region of the connecting stalk. Here, the gut tube maintains an attachment to the yolk sac. The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to the embryo, which provides nutrients and functions as the circulatory system of the very early embryo.[3]

The lateral body wall folds, pulling the amnion in with it so that the amnion surrounds the embryo and extends over the connecting stalk, which becomes the umbilical cord, which connects the fetus with the placenta. If the ventral body wall fails to close, ventral body wall defects can result, such as ectopia cordis, a congenital malformation in which the heart is abnormally located outside the thorax. Another defect is gastroschisis, a congenital defect in the anterior abdominal wall through which the abdominal contents freely protrude. Another possibility is bladder exstrophy, in which part of the urinary bladder is present outside the body. In normal circumstances, the parietal mesoderm will form the parietal layer of serous membranes lining the outside (walls) of the peritoneal, pleural, and pericardial cavities. The visceral layer will form the visceral layer of the serous membranes covering the lungs, heart, and abdominal organs. These layers are continuous at the root of each organ as the organs lie in their respective cavities. The peritoneum, a serum membrane that forms the lining of the abdominal cavity, forms in the gut layers and in places mesenteries extend from the gut as double layers of peritoneum. Mesenteries provide a pathway for vessels, nerves, and lymphatics to the organs. Initially, the gut tube from the caudal end of the foregut to the end of the hindgut is suspended from the dorsal body wall by dorsal mesentery. Ventral mesentery, derived from the septum transversum, exists only in the region of the terminal part of the esophagus, the stomach, and the upper portion of the duodenum.[4]

Function

These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions.

Anatomical structures are often described in terms of the cavity in which they reside. The body maintains its internal organization by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments.

The lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, for example, can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.[2] The ventral cavity includes the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities and their subdivisions. The dorsal cavity includes the cranial and spinal cavities.[2]

Other animals

Organisms can be also classified according to the type of body cavity they possess, such as pseudocoelomates and protostome coelomates.[5]

Coelom

In amniotes and some invertebrates the coelom is the large cavity lined by mesothelium, an epithelium derived from mesoderm. Organs formed inside the coelom can freely move, grow, and develop independently of the body wall while fluid in the peritoneum cushions and protects them from shocks.

Arthropods and most molluscs have a reduced (but still true) coelom, usually the pericardial cavity and the gonocoel. Their principal body cavity is the hemocoel or haeomocoel of an open circulatory system, often derived from the blastocoel.

See also

References

This Wikipedia entry incorporates text from the freely licensed Connexions edition of Anatomy & Physiology text-book by OpenStax College

- Ehrlich, A.; Schroeder, C.L. (2009), "The Human Body in Health and Disease", Introduction to Medical Terminology (Second ed.), Independence, KY: Delmar Cengage Learning, pp. 21–36

- "Anatomy & Physiology". Openstax college at Connexions. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- Sadler (2012). LANGMAN Embriología médica. I (12 ed.). Philadelphia, PA: The Point.

- Tortora, Gerard; Derrickson, Bryan (2008). Principios de anatomía y fisiología. I (11 ed.). Buenos Aires: Panamericana.

- "Animals III — Pseudocoelomates and Protostome Coelomates". Archived from the original on 2009-04-06.