Abraham Peyrenc de Moras

Abraham Peyrenc de Moras (1684 – 20 November 1732) was a French banker. Though descended from commoners and often described as the son of a barber, his family began its ascent in the 17th century since his grandfather was a hat merchant and his father a licensed surgeon, tax collector and a bourgeois of the city. Abraham surpassed them and experienced a meteoric social ascent in 18th century Paris, cemented by his being made noble in 1720.

Abraham Peyrenc de Moras | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Abraham Peyrenc, marquis de Moras | |

| Born | Abraham Peyrenc 1684 Le Vigan, Gard, France |

| Died | November 20, 1732 (aged 47–48) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Banker |

| Years active | 1720-1732 |

| Known for | Constructing Hôtel Biron, which now houses the Musée Rodin |

His beginnings in Paris

Decisive encounters

Abraham, the fourth of the Peyrenc children, was born in 1684 and baptized as a Protestant in the church at Aulas, a few miles northwest of Le Vigan. His father was a licensed surgeon. A country surgeon, whose profession dealt with the body, could at times serve as barber.[1] He was able to purchase the post of secretary to the king and lands at Saint-Cyr. Some of his children left France for England in order to continue to exercise their faith.[2] Abraham left le Vigan around 1703. According to some, he fled to Geneva.[3] where he met with members of the Bégon family, who were also from le Vigan, and like himself had left for religious reasons. The Bégons were in banking and following them, he took a liking to the business world. According to others, he went to Lyon, where he began his career as assigned and then began to associate with Simon Le Clerc, a clothing merchant. In either case, he followed a path to Paris where he gained wealth and converted to Catholicism.

His biographer, the marquis de Lordat, writes: “the strict huguenot that he believed himself to be yielded at first contact with the larger world. It gave way in contact with an environment where one dreams only of material gain, of the accumulation of riches, and ceded to the golden calf.”

Others prefer to have fun and tell a good story:[4]

One pleasant morning, a new Cadet of Gascogne, the young Abraham set out for the capital; but in place of a sword, he carried a comb: because for starters, his hand was forced, and he couldn’t hope to live by his father’s occupation alone. The situation of a young hairdresser opened but modest horizons for an ordinary man, but this one was well made, spiritual, and coming with the endorsement of his precursor Gil Blas, he succeeded in making himself appreciated by a rich bourgeois who took him into his service. Thus Abraham Perrin becomes valet to the house barber of François-Marie Fargès. He was an important master, ex-soldier, then purveyor… entitled to 500,000 pounds in interest. This last quality seems to have hypnotized Perrin. Fargès had a daughter 16 years of age… The valet became son-in-law to his master.

With this man who came from nothing to become the purveyor general of the king’s armies, Abraham is at the right school. He served as secretary, then right hand man, and eventually son-in law. He married Anne-Marie-Josèphe de Fargès who gave him three children, one of whom was François Marie Peyrenc de Moras, who became contrôleur général des finances to Louis XV.

Doing so he followed the example of his father-in-law who was in his youth noticed by Lord Lagrange, a contractor in fodder and fortifications, hired by him, and in the end brought into the business. His marriage to the daughter of his employer was the springboard of his success, insomuch as he became a purveyor, one of the fastest methods to enrich oneself.

Fargès Company as a springboard into the world of Finance

Under the reign of Louis XIV, wars followed one upon another, and the Secretary of State at war finished each years’ contracts with groups of several contractors called “purveyors” (“munitionnaires”) which undertook to furnish bread rations at a suitable price, fodder, horses, food and clothes necessary for garrisons or troops in combat for the duration of each campagne.[5] These contracts could reach values in the millions of Pounds. The munitionnaires would see only a quarter of this sum. The account was calculated with of bills of exchange guaranteed by the War Treasury. The purveyor interested in keeping payments low would sed the price of goods with food vendors, by means of bills of exchange payable at a specified time with the banker with whom they were drawn.

If the Fargès business was founded in 1710, it had its lucrative beginning well beforehand. Its role was not limited to purchases. It acted as banker by loaning out considerable sums. In 1707 it called its debts with the Comptroller General of Finance, being four million Pounds. The success of Fargès was linked to its collaboration with an international network of subcontractors and bankers wielding control over currency exchange and credit. Due to late payments of advances promised by the Secretary of State (Daniel Voysin de la Noiraye), Fargès was at prey to problems in the treasury in 1712 and 1715, and he had to suspend payments. He was however considerably enriched by dealing in bills of the War Treasury, just like Abraham. Abraham was apprehensive in 1715, after the death of Louis XIV, because the Regent decided to prosecute bankers guilty of embezzlement. Taxed at more than 2 million Pounds, he preferred to exile himself for several months in England. Having returned to France, he launched a new endeavor with Fargès.

Since the revival of business was indispensable to the restoration of the Royal Treasury, the Regent gave his agreement to the Scotsman John Law, who founded in Paris, in the rue Quicampoix, a joint stock private bank. The financial system included in 1717 the creation of the French East India Company which rested on the development of Louisiana. Shares were traded for gold but they could also be paid through government notes. Prices rose, shares for 150 were bought for up to 10,000 pounds. The bank which became Royal was given a monopoly on minting coins.

Enrichment through the ‘Système de Law’

Fargès underwrote the French East India Company for a million Pounds and was counted among the great men of Mississippi. He sold his shares before the system collapsed in 1720. He gave 27 million in Letters of Exchange during the Opération du visa for which he received 20 Million in new bonds. Having become extremely rich, he purchased two offices of secretary to the King, one for himself and the other for his father, the Royal Notary to the Monts du Lyonnais.

With so good a master, Abraham Peyrenc as well made his way. He became one of the most driven bankers of the capital. As early as 1719, his fortune was made and he could retire from business and enter into government. In 1720 he purchased the post of secretary to the King and was given Nobility. He purchased lands. But his landed nobility was not enough, he wanted to have the status of noblesse de robe, for which he had to learn both Latin and the Law. He surrounded himself with masters who taught these to him and made him a lawyer, which was necessary for him to purchase the post on the council of State, which cost a fortune, over 200,000 pounds. Between 1720 and 1722 he was an advisor at the Parlement de Metz then maître des requêtes. Being brought into the confidences of Louise Françoise de Bourbon, Duchess of Bourbon, the legitimate daughter of Louis XIV, he was named her chief of council in 1723. In Mars of the same year, he became a member of the office of the Prime Minister to the Indes, and in August he was made chief Inspector.[6] The crowning moment was in 1731 when he became Kings Commissioner for the company. A commissioner reports only to the Controller General of Finances, thus he was the true master of the company.

His portrait (now at the Musée cévenol) is the proof of his social climb, and his entrance into the nobility. It expresses the desire to create a new nobility which attempts to follow the aristocratic model. The aesthetics of the portrait are attributed at times to Nicolas de Largillière, at others to Hyacinthe Rigaud, hesitating between an official portrait, pompous and uptight, and a psychological portrait. Abraham Peyrenc, who acquired the marquisat of Moras, was eternalized in a slight three-quarters pose, smiling amicably, his look without insolence, in a curly wig without stiffness, dressed in silk velvet suit, adorned with lace. The human qualities of his personality are placed in the foreground, much more than his occupation or his wealth. The arms he chose reflect his path from le Vigan: from the opening, sewn with gold nuggets, to the brocaded gold band.

Purchase of lands and real estate

As a prudent Cévenol, Peyrenc retired from business, his fortune made, and used his money in the purchase of various lordships. Between 1719 and 1720, he acquired estates (worth 1,089,400 Pounds), and in the decade following invested 1,662,767 pounds into real estate. He seems to have acquired his lands whenever the occasion presented itself.[7]

On 5 August 1719, he purchased from the duchess of Brancas the lordship of Moras (near La Ferté-sous-Jouarre in Brie), which was valued at 118,400 pounds and brought him both his noble title and his family name “Peyrenc de Moras.” On October 3 of the same year, he purchased from the Viscount of Polignac’s creditors both lands, titles, and dependencies at d’Ozon, Rioux, Saint-Amant, Roche-Savine, Boutonargues, Saint-Pal, Châteauneuf-de-Randon which were valued at 546,000 pounds. On January 4, he purchased a large house at Montfermeil four leagues from Paris, and on October 11 of the same year, the Barony of Peyrat, and on February 21 two building sites at place Louis-le-Grand (now Place Vendôme). He became lord of the city of Saint-Etienne en Forez, one of the largest manufacturing cities in the kingdom, with the purchase of his second Lordship title (at Saint-Priest-en-Jarez from the Saint-Priest/Durgel/Jarez Family, valued at 400,000 pounds). In 1725 he paid off the gambling debts of Léonard Hélie de Pompadour, grand sénéchal of Périgord and marquis of Laurière, in exchange for his titles (his third marquisat).[8] In May of 1728, he acquired the title of Count (comté) of Clinchamp in Perche, valued at 450,000 pounds, then in June, lands at Champrose, Menillet, Villemigeon near Tournan-en-Brie. Though already impressive, this list is not exhaustive and excludes several fiefs and Parisian homes rented out or purchased for resale.

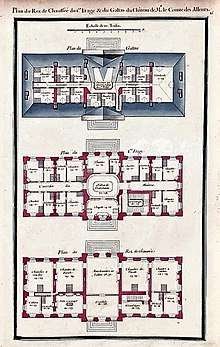

Having acquired through law two building sites on place Louis-le-Grand, M. de Moras asked the architect Jacques Gabriel to purchase a third lot on which to build two beautiful homes. The largest was sold to Jean de Boullonges, chief commissioner of Finance, the other to the marquis of Alleurs to enjoy during his life as well as to his brother le chevalier des Alleurs, for part of the price of the lands at Clinchamp.

In the country, the Moras family had a number of beautiful mansions among which were the house at Montfermeil, four leagues from Paris, and the château de Champrose, nine leagues distance from the city, also in Brie, Cherperine (Chèreperrine), Perche, and Origny-le-Roux. The château de Moras seems to have been lived in. The inventory after death describes a chateau whose interior was without lustre, of which the tapestries were old, the flooring and furniture used, and the mirrors and trumeaux coming unglued. There are portraits of the late Louis XIV and other kings or lords. M. de Moras liked paintings inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphosis, or motifs of flowers, fruits, and hunting, in the mansions in which he lived. The panel above the door at Montfermeil and in the hôtel de Varennes are examples of such. The chandeliers were of german cristal, the marble from Italy, the commodes of rosewood. The château de Cherperine served as vacation house in the pleasant months.

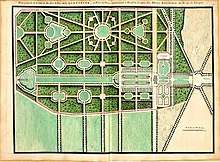

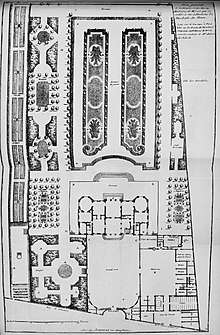

In 1727 the Moras family lived in Paris in an hôtel particulier built by Jacques Gabriel which stands today in the Place Vendôme. Judging the habitation unworthy of himself, M. de Moras decided to have built another. He wanted to show off his magnificence in front of the old Nobility and to dazzle them with his Luxury, a revenge of the upstart. He therefore purchased large tracts of land at the end of the rue de Varennes, in a new practically empty neighborhood far from the noise of Paris, near the hôtel des Invalides. It was an uneven terrain filled in from old sandpits.[9] The choice of this place for the construction of his Mansion was not insignificant.[10] Besides its proximity to the Palais Bourbon, where the duchess dowager Louise Françoise de Bourbon for whom he served as Chief of Council, no other area had as much land available for construction. The building of Les Invalides resulted in the urbanization of this area still outside the city. Additionally, its streets parallel to the Seine offered land of sufficient length to erect habitations between courtyards and gardens. M. Peyrenc de Moras first purchased a parcel of 5 hectares and then exchanged other lands with the marquis de Saissac in order to have an area a bit larger than 1 sq. km.

_(4528252634).jpg)

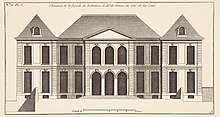

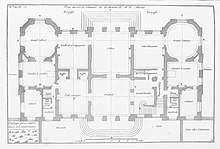

Once in possession of the lands, he wrote to Jacques V Gabriel, the king’s inspecter general of buildings, who entrusted the design and construction of the building to Jean Aubert, one of the king’s architects. This building would later become known as the Hôtel Biron which houses the Musée Rodin today. Jean Aubert designed the hôtel in 1727, with a courtyard in front and garden behind, set off on both sides and erected in a real park, like a château.[11][12] It was simultaneously a townhouse and a vacation home. The parcel of such large size allowed him to frame the building in greenery which completely surrounded it, except for a part to the right of the courtyard. The gardens are visible from each room, even the ones on each side. A central corridor, an innovation from the 18th century which was only possible because a lack of central walls, distributed the rooms along both sides, with light coming in part from side windows at each end. Isolated on a platform a few steps up, the building has three levels: a mezzanine broken by windows capped in lowered arcs, a first floor, and a second level separated by a band of moulding. The main building covers a surface of 354 sq. meters, the main courtyard is 32 meters wide by 48 deep. The very large stables held 32 horses. The plans followed by Jean Aubert are in the purist spirit of rococo, in fashion at the time. The ground plans, cross section, and elevations as well as the garden blueprint were featured in Jacques-François Blondel's Architecture française (1752).[13]

_1727.jpg)

In 1729, M. Peyrenc de Moras commissioned from François Lemoyne 18 decorative paintings, inspired by the Metamorphoses, most of which were to go above the doors.[15] The great room was adorned with “the four times of day”: Aurore and Céphale to illustrate morning, Venus Showing Eros the Passion of his Arrows for noon, Diana Returning from the Hunt for evening, and Diana and Endymion for night. The theme of the series was Amor vincit omnia (‘love conquers all’).

The Legacy left by Abraham Peyrenc de Moras

In 1731, the family of Peyrenc de Moras moved in. But the father of the house did not profit long from the magnificence of his mansion, as he died before the completion of the second level. His widow rented the house to the duchesse du Maine in 1736. At the death of whom, the heirs of Moras sold the building, valued at 500,000 pounds, to the duc du Biron.

A figure for posterity

The banker’s renown grew in his posterity, so steep had been his social ascension. It left none indifferent to him, earning the scorn of some, and the admiration of others. At the announcement of his death, the songwriter Charles Collé said: “We lost yesterday one of our Croesus, M. de Moras, who “left between 8-900,000 pounds in interest, palaces, chateaux, great lands, and all this acquired in a short time. He wasn’t even 50.” Edmond Jean François Barbier wrote similar things about Moras in his newspaper.

November 1732

The 20th day of this month, we will bury one named Peirenc de Moras, 46 years old, chief solicitor and chief counselor to Mme la Duchess Dowager. This man was son of a barber in a small town in Saintonge (sic), and he himself shaved. He came thence to paris which is the refuge of all kinds of people. He bartered, negotiated in the square before the famous 1720 système de Law. He had more bad than good deals, but having nothing to risk, he put his all into the system. He had the good fortune to achieve his goals. He had a sense for knowing which paths to follow in this land. In the end, he died rich to the tune of 12-15 million, as much in funds as in lands and goods, jewels and shares in the East India Company. He had constructed in the faubourg Saint-Germain the most beautiful house that has existed in Paris. This alone suffices for a picture of our government. See here a man nothing who in two years time became more rich than princes, and this fortune, produced by this unhappy system, is composed of the losses of two hundred individuals that they had acquired or inherited, over thirty years of work in all manner of professions. Even so, this man was left alone because he was in a position to distribute a thousand to lords and people of the court, and he was placed in an honorable judiciary office. He leaves behind a widow and three children. His widow is the daughter of Fargès, former purveyor of rations, trained as a soldier, who enjoyed 500,000 pounds interest, and who has the secret of not having paid one of his creditors. There is already more than one lord who dreams of marrying this widow.

Contradictory commentaries very often fall into gossip. Many remember only the old valet or the barber, others imagine he purchased silence about his origin by the generous loans he gives. The Vicount de Reiset is the most generous, who said of M. de Moras that was is respected and honored by all Paris society, adding that his widow received the most sought after men in town and at court. This was contested by those who imagine that she received needy gentlemen, obliged them in every way, and gave them good food and lodging. Hadn’t she as much as thrown her daughter into the arms of a provincial gentleman out of money who hastened to marry her once she fled her convent to join him? The death of Mme de Moras, on January 11, 1738, is supposed to have been caused by this scandal. Often illusions were made to her foolish spirit, sassy and stubborn. She is supposed to have lived a libertine and debauched life, especially after the death of her husband.

It is clear that if the story of the marquis de Moras still makes it into the publications of the 19th and early 20th century, it is that of his “hôtel particulier,” sold first to the duke de Biron, and then converted to the Sacré-Cœur convent, before becoming the Musée Rodin, each time an occasion for journalists to bring up the story of its first owner, one so romantic it resembles a serial novel.

The Legacy left to his Family

.jpg)

In his lifetime, Abraham Peyrenc de Moras did not neglect his family.[16] Thanks to his protection, his younger brother Louis became lord of Saint-Cyr and, in 1735, his daughter married François-Jean-Baptiste de Barral de Clermont, a councilor in Parlement to the dauphin and subsequently Président à mortier. The other brother who had no political ambition became the abbé Moras of the congrégation de Saint-Antoine, in Metz. At his death, M. de Moras left his wife and his three children a colossal fortune which would be of most use to the oldest, François Marie Peyrenc de Moras, in establishing himself and becoming first steward and then minister. His youngest son, commissioner of petitions for the palais, died relatively young. His daughter Anne-Marie, whose incredible engagement to Louis de Courbon was broken off, ended up remarrying the Count Merle de Beauchamp, ambassador to Portugal.

L' inventaire après décès a été déposé auprès du notaire de famille parisien, Thomas-Simon Perret[17]

He employed various notaries between november 1732 and February 1733. It includes an impressive number of pages. It is true that the fortune of M.de Moras is estimated at 5,849,702 pounds of which 2,337017 is in real estate.[18] Therein leases of innumerable farms in various regions are recorded: Vivarais, Forez, Auvergne, Limousin, Perche, Brie, Bas-Poitou. The leases of the farms due at Christmas 1732 alone, including those of mills, forests, ponds and tuileries, reach a value of 83,706 pounds. M. de Moras received in Paris the rents of 18 tenants at Croix-Rouge, rue Cassette, Place Maubert, rue de Vendôme and rue de Saint-Jacques. Many people owed him arrears on the annuities they contracted from him, among these the Duke de NeversM. de Caumartin, M. and Mme de la Rochefoucault (marquis de Bissy). His monthly salary is a drop in the bucket, compared to the previous sums: 4620 pounds. Among his châteaux and Mansions, only the château de Moras, de Champrose, de Cherperine, la maison de Monfermeil and l'hôtel de la rue de Varenne (which was later sold for 450000 pounds) are counted by his heirs on May 7, 1758. Excluded from this inventory are the house on rue des Capucines, acquired in 1729, the château de Livry, and above all the stock in the East India Company (125 shares), which represents a sum of 2,250,000 pounds.

References

- "Histoire des chirurgiens, barbiers et barbiers chirurgiens"..

- Christian Sigel (December 2012). Histoire et mémoire Le temps des Peyrenc. Bulletin du Vieux Saint-Etienne. pp. 5–14, 48..

- Club cévenol (Alès, Gard). Auteur du (1970). "Causses et Cévennes : revue du Club cévenol : trimestrielle, illustrée / dir. Paul Arnal ; réd. Louis Balsan". Gallica (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-24..

- "Untitled-Société historique de Compiègne" (PDF)..

- Thèse intitulée : de la dentelle à la finance: Parcours d'une femme d'affaires au début du XVIIIe siècle (Université de Louvain)

- Philippe Haudrère (1980). "L'origine du personnel de la direction générale de la compagnie française des Indes". Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer (in French). 67 (248–249). pp. 339–371.

- Christian Sigel (2012). Histoire et mémoire, le temps des Peyrenc (in French). Histoire et Patrimoine de Saint-Etienne. pp. 11–12.

- Archives nationales, MC/ET/XCV/83 (12 July 1725)

- Jean-Charles-Marie Roger, marquis de Lordat (1785). Les Peyrenc de Moras (1685-1785) une famille cévenole au service de la France (in French).

- "Ateliers et domiciles de Rodin, Etude des cadastres" (PDF) (in French).

- "L'hôtel Peyrenc de Moras, ensuite Biron".

- https://www.nytimes.com/1986/05/18/travel/a-paris-house-of-rodin-and-royalty.html

- "Illustrations de l'architecture française ou recueil des plans" (in French).

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b2100070r

- "Alain. R. Truong ( tableau de François Le Moyne)" (in French).

- "Rodin à l'hôtel de Biron et à Meudon par Gustave Coquiot".

- Archives nationales, MC/ET/XCV/119 inventaire des biens après décès (25 novembre 1732)

- Thierry Claeys. Dictionnaire biographique des financiers en France au XVIIIe siècle. SPM Kronos. pp. Tome 2.

See also

- Le Vigan.

- Museum of the Cevennes (Musée Cévenol). Portrait of Abraham Peyrenc de Moras.