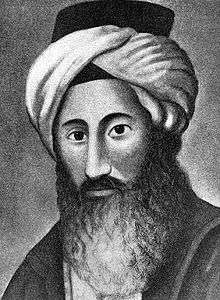

Abraham Khalfon

Abraham Khalfon (Hebrew: אברהם כלפון, Avraham Khalfon, 1741–1819)[1][2] was a Sephardi Jewish community leader, historian, scholar, and paytan in Tripoli, Libya. He researched an extensive history of the Jews of Tripoli that served as a resource for later historians such as Abraham Hayyim Adadi, Mordechai Ha-Cohen, and Nahum Slouschz, and also composed piyyutim (liturgical poems) and kinnot (elegies).

Abraham Khalfon | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | Abraham Khalfon 1741 Livorno, Italy |

| Died | September 25, 1819 (aged 77–78) Safed, Palestine |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Children | Rahamim David Nehorai |

| Parents | Raphael Khalfon |

| Position | Community leader |

| Organisation | Jewish community of Tripoli |

| Began | 1778 |

| Ended | 1795 |

| Yahrtzeit | 6 Tishrei 5580 |

| Buried | Safed |

Biography

Abraham Khalfon was born in Livorno, Italy, to Raphael Khalfon, a wealthy Jewish philanthropist whose family were community leaders in Tripoli.[1] His brit milah was performed by Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar, the Ohr HaHayyim, who was visiting Livorno that year with 100 other rabbis.[1] He was raised in Tripoli.[1]

Khalfon became active in communal affairs at the age of 25.[1] He served two three-year terms as Jewish community leader, from 1778 to 1781 and from 1792 to 1795.[3] As part of his duties, he represented the community before the Ottoman Sultan, who wielded overall control of Tripoli.[1] Khalfon also served as an advisor to Ali Pasha of the Karamanli dynasty, which directly ruled Tripoli, regarding taxation of the Jewish community.[1]

In his later years, Khalfon became less involved in his communal and business interests and devoted his time to Torah study.[1] He had a close relationship with the Chida, who lived in Livorno. Khalfon helped disseminate the Chida's works in Libya and also traveled to Livorno to study in the Chida's beit medrash for a year and a half, from 1804 to 1805.[1][3]

In 1806, Khalfon emigrated to Safed, Palestine,[3] where he engaged in Torah study for the rest of his life.[1] He died in Safed on Shabbat Shuvah 1819 (6 Tishrei 5580).[1]

Works

Halakha

Khalfon authored Hayyei Avraham (Hebrew: חיי אברהם, "Life of Abraham"), a commentary on the mitzvot in the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim and Yoreh Deah) based on the Talmud, Zohar, and commentaries on the Zohar. While he wrote this work in 1780,[1] it was printed posthumously in 1826 by his son Rahamim.[4] It was reprinted in 1844, 1857, and 1861.[4]

Khalfon's responsa, Leket HaKatzir (Hebrew: לקט הקציר, "Gathering the Harvest"), was printed for the first time in Israel in 1992.[1]

History

Khalfon produced a history of the Jews of Tripoli from ancient times until his own day, culling government archives, rabbinical court documents, and genizah records.[1][2][5] His Hebrew-language work, called by others Seder HaDorot (Hebrew: סדר הדורות, "Book of Generations"), was an important source for Abraham Hayyim Adadi's historical writings about Tripoli minhagim (customs) in the mid-nineteenth century.[6][7] Tripoli historian Mordechai Ha-Cohen (1856–1929) liberally quotes from Khalfon's work in his chronicle of Jewish and Muslim life in nineteenth-century Tripoli.[2][8] Nahum Slouschz also quotes Khalfon in his 1927 history of the Jews of North Africa, such as Khalfon's description of the origins of the Tripoli Jewish community:

"Among the older people I found a tradition, handed down to them by their ancestors, that at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem, one of the generals of Titus, Phanagorus, King of the Arabs, led a number of captive Jews into the mountains, two days distant from Tripoli, and there handed them over to the Arabs. From these mountains they came to Tripoli".[9][10]

Although a copy of Khalfon's manuscript was kept in the rabbinical court of Tripoli, it was not brought to Israel with the Libyan Jewish emigration after 1948 and was lost.[6]

Other works by Khalfon include a summary of ancient regulations and a collection of piyyutim.[11] In 1800 Khalfon traveled to Tunis and recorded the piyyutim of the great paytanim of that country, including Rabbi Faraji Shawat and Rabbi Eliyahu Sedbon.[1]

Poetry

Khalfon composed both piyyutim (liturgical poems) and kinnot (elegies), most of which are still in manuscript form. His elegy for his murdered son, David, and his piyyut, Mi Kamokha (Hebrew: מי כמוך, "Who is like You"), both stemmed from the reign of terror perpetrated by Ali Burghul against the Jews of Tripoli from July 30, 1793, to January 20, 1795.[12] Before that time, Tripoli's Jews had been benignly ruled by Ali Pasha of the Karamanli dynasty for some three decades. However, a fratricidal war between two sons of Ali Pasha and an attempt by the victorious son, Yusuf Karamanli, to seize the throne plunged the city into chaos. Ali Burghul, an Algerian corsair, took advantage of the situation and usurped control.[13][14] Ali Burghul imposed heavy taxes and engaged in many acts of robbery and blackmail against the population, and gave his soldiers free rein to terrorize the residents, particularly Jews.[15][16] Khalfon's son David, who had joined a plot to overthrow Ali Burghul, was burned at the stake along with other Jewish conspirators.[1][17][18]

On January 20, 1795, Ali Burghul was ousted by Yusuf Karamanli with the aid of the bey of Tunis.[19] To celebrate their rescue from a modern-day Haman, the Tripoli Jewish community established a Second Purim called Purim Burghul on 29 Tevet.[lower-alpha 1][14][16][20] Khalfon's piyyut describing Ali Burghul's rise and fall became part of the annual liturgy in Tripoli on the Shabbat before 29 Tevet.[1][15]

Personal

Two of Khalfon's sons died in his lifetime – David, who was executed by Ali Burghul, and Nehorai, who died in a plague that ravaged Tripoli in 1785.[1]

Notes

- January 20, 1795, corresponded to 29 Tevet on the Hebrew calendar.

References

- Pedatzor, Benetiya (26 January 2004). "ר' אברהם כלפון" [Rabbi Abraham Khalfon]. Or-Shalom (in Hebrew). Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- Meddeb & Stora 2013, p. 237.

- "Khalfon, Abraham". Brill Online. 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- Skolnik & Berenbaum 2007b, p. 273.

- Goldberg 1993, p. 3.

- Hirschberg 1981, p. 150f.

- Skolnik & Berenbaum 2007a, p. 370.

- Goldberg 1993, p. 4.

- Slouschz 1927, p. 154.

- Williams 1999, p. 199.

- Hirschberg 1981, p. 180.

- Stewart 2006, p. 225.

- Hirschberg 1981, pp. 153–154.

- Goldberg, Harvey E. (Fall 2010). "Purim and its Relatives in Tripoli: A Comparative Perspective on the Social Uses of Biblical Stories". Sephardic Horizons. 1 (1). ISSN 2158-1800.

- Hirschberg 1981, p. 154.

- Stillman & Zucker 2012, p. 85.

- Singer & Adler 1964, p. 262.

- Mendelssohn 1920, p. 62.

- Hirschberg 1981, p. 156.

- Hirschberg 1981, pp. 153–156.

Sources

- Goldberg, Harvey E., ed. (1993). The Book of Mordechai: A Study of the Jews of Libya. Darf Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirschberg, H. Z. (1981). A History of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time. II. Brill. ISBN 9004062955.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meddeb, Abdelwahab; Stora, Benjamin, eds. (2013). A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the origins to the present day. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-15127-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mendelssohn, Sidney (1920). The Jews of Africa: Especially in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited.

halfon.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus, eds. (1964). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 12 (reprint ed.). Ktav Pub. House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael, eds. (2007a). Encyclopaedia Judaica. 1. Granite Hill Publishers. ISBN 0-02-865929-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael, eds. (2007b). Encyclopaedia Judaica. 9. Granite Hill Publishers. ISBN 0-02-865936-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slouschz, Nahum (1927). Travels in North Africa. Jewish Publication Society of America.

halfon.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Stewart, John (2006). African States and Rulers (3rd ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2562-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stillman, Yedida K.; Zucker, George K., eds. (2012). New Horizons in Sephardic Studies. SUNY Press. ISBN 1-4384-2131-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Joseph J. (1999). Hebrewisms of West Africa: From the Nile to Niger with the Jews. Black Classic Press. ISBN 1-58073-003-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Hayyei Avraham at HebrewBooks.org