Abgar Legend

The Abgar legend, according to Christian tradition, posits an alleged correspondence and exchange of letters between Jesus Christ and King Abgar V Ukkāmā of Osroene.[1][2][3][4] In the fourth century Eusebius of Caesarea published two letters which were allegedly discovered in the archives of Edessa.[5][6] They claim to be an exchange of correspondence between Jesus Christ and King Abgar V which were written during the last years of Jesus' life.[7]

Abgar V was king of Osroene with his capital city at Edessa, a Syrian city in upper Mesopotamia. According to the legend, King Abgar V was stricken with leprosy and had heard of Jesus’ miracles. Acknowledging Jesus' divine mission, Abgar wrote a letter of correspondence to Jesus Christ asking to be cured of his ailment. He then invited Jesus to seek refuge in Edessa as a safe haven from persecution. In his alleged reply, Jesus applauded the king for his faith but turned down the request. He expressed regret that his mission in life precluded him from visiting the city. Jesus blessed Abgar and promised that after he ascended into heaven, one of his disciples would heal all of the illnesses of the king and his subjects in Edessa.[8]

Development of the Abgar Legend

The story of how King Abgar and Jesus had corresponded was first recounted in the 4th century by the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea in his Ecclesiastical History (i.13 and iii.1) and it was retold in elaborated form by Ephrem the Syrian in the fifth-century Syriac Doctrine of Addai.[9]

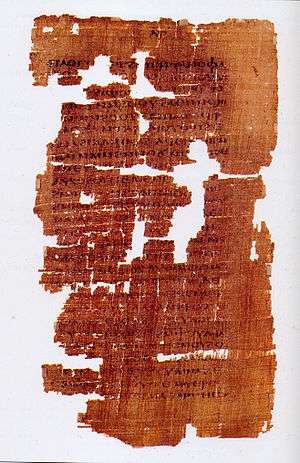

An early version of the Abgar legend exists in the Syriac Doctrine of Addai, an early Christian document from Edessa. The Epistula Abgari is a Greek recension of the letter of correspondence exchanged between Jesus Christ and Abgar V of Edessa, known as the Acts of Thaddaeus.[10] The letters were likely composed in the early 4th century. The legend became relatively popular in the Middle Ages that the letters were translated from Syriac into the Greek, Armenian, Latin, Coptic[11] and Arabic languages.[3][1][12]

Historical Context

Eusebius contains the earliest known account of the Abgar Legend in his first book Ecclesiastical History (ca. 325 C.E.), as part of his discussion of Thaddeus of Edessa. Eusebius claims that Thaddeus went to Abgar at the request of Thomas the Apostle, following Jesus’ resurrection. He also claims to provide the correspondence between Abgar and Jesus, which he translates from Syriac.

Letter of Abgar to Jesus

The church historian Eusebius records that the Edessan archives contained a copy of a correspondence exchanged between Abgar of Edessa and Jesus.[13][14] The correspondence consisted of Abgar's letter and the answer dictated by Jesus. On August 15, 944, the Church of St. Mary of Blachernae in Constantinople received the letter and the Mandylion. Both relics were then moved to the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos.[15]

A curious growth has arisen from this event, with scholars disputing whether Abgar suffered from gout or from leprosy, whether the correspondence was on parchment or papyrus, and so forth.[16]

The text of the letter was:

Abgar, ruler of Edessa, to Jesus the good physician who has appeared in the country of Jerusalem, greeting. I have heard the reports of you and of your cures as performed by you without medicines or herbs. For it is said that you make the blind to see and the lame to walk, that you cleanse lepers and cast out impure spirits and demons, and that you heal those afflicted with lingering disease, and raise the dead. And having heard all these things concerning you, I have concluded that one of two things must be true: either you are God, and having come down from heaven you do these things, or else you, who does these things, are the son of God. I have therefore written to you to ask you if you would take the trouble to come to me and heal all the ill which I suffer. For I have heard that the Jews are murmuring against you and are plotting to injure you. But I have a very small yet noble city which is great enough for us both.[17]

Jesus gave the messenger the reply to return to Abgar:

Blessed are you who hast believed in me without having seen me. For it is written concerning me, that they who have seen me will not believe in me, and that they who have not seen me will believe and be saved. But in regard to what you have written me, that I should come to you, it is necessary for me to fulfill all things here for which I have been sent, and after I have fulfilled them thus to be taken up again to him that sent me. But after I have been taken up I will send to you one of my disciples, that he may heal your disease and give life to you and yours.[18]

Egeria wrote of the letter in her account of her pilgrimage in Edessa. She read the letter during her stay, and remarked that the copy in Edessa was fuller than the copies in her home (which was likely France).[19]

In addition to the importance it attained in the apocryphal cycle, the correspondence of King Abgar also gained a place in liturgy for some time. The Syriac liturgies commemorate the correspondence of Abgar during Lent. The Celtic liturgy appears to have attached importance to it; the Liber Hymnorum, a manuscript preserved at Trinity College, Dublin (E. 4, 2), gives two collects on the lines of the letter to Abgar. It is even possible that this letter, followed by various prayers, may have formed a minor liturgical office in some Catholic churches.[17]

This event has played an important part in the self-definition of several Eastern churches. Abgar is counted as saint, with feasts on May 11 and October 28 in the Eastern Orthodox Church, August 1 in the Syrian Church, and daily in the Mass of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The Armenian Apostolic Church in Scottsdale, Arizona, is named after Saint Abgar (also spelled as Apkar).

Critical scholarship

The scholar Bart D. Ehrman cites evidence from Han Drijvers and others for regarding the whole correspondence as forged in the third century by orthodox Christians "as an anti-Manichaean polemic", and entirely spurious.[20]

A number of contemporary scholars have suggested origins of the tradition of Abgar's conversion apart from historical record. S. K. Ross suggests the story of Abgar is in the genre of a genealogical myth which traces the origin of a community back to a mythical or divine ancestor.[21] F. C. Burkitt argues that the conversion of Edessa at the time of Abgar VIII was retrojected upon the Apostolic age.[22] William Adler suggests the origin of the story of the conversion of Abgar V was an invention of an antiquarian researcher employed by Abgar VIII, who had recently converted to Christianity, in an effort to securely root Christianity in the history of the city.[23] Walter Bauer, on the other hand, argued the legend was written without sources to reinforce group cohesiveness, orthodoxy, and apostolic succession against heretical schismatics.[24] However, several distinct sources, known to have not been in contact with one another, claimed to have seen the letters in the archives, so his claim is suspect.[25]

Significant advances in scholarship on the topic have been made[26] by Desreumaux's translation with commentary,[27] M. Illert's collection of textual witnesses to the legend,[28] and detailed studies of the ideology of the sources by Brock,[29] Griffith,[30] and Mirkovic.[31] The majority of scholars now claim the goal of the authors and editors of texts regarding the conversion of Abgar were not so much concerned with historical reconstruction of the Christianisation of Edessa as the relationships between church and state power, based on the political and ecclesiastical ideas of Ephraem the Syrian.[32][33][31] However, the origins of the story are far still from certain,[34] although the stories as recorded seem to have been shaped by the controversies of the third century CE, especially as a response to Bardaisan.[32]

See also

- Abgar V

- Image of Edessa

- Doctrine of Addai

- Eusebius of Caesarea

References

- "Abgar legend | Christian legend". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

Abgar legend, in early Christian times, a popular myth that Jesus had an exchange of letters with King Abgar V Ukkama of Osroene, whose capital was Edessa, a Mesopotamian city on the northern fringe of the Syrian plateau.

- Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey; McKnight, Edgar V. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

Abgar Legend, [ab'gahr] The Abgar legend concerns a supposed exchange of letters between King Abgar V of Edessa (9—46 c.e.) and Jesus, and the subsequent evangelization of Edessa by the apostle Thaddeus

- Ross, Steven K. (2000-10-26). Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114 - 242 C.E. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 9781134660636.

According to the legend a King Abgar (supposedly Abgar V Ukkama, Jesus' contemporary) wrote to Jesus in Jerusalem asking to be healed and inviting Jesus to visit Edessa. The text of that letter, and Jesus' reply, exist in many versions in almost all the languages of the Roman Empire, in keeping with the belief that the texts themselves had a sanctifying and protective power. The importance of this legend for the reputation of the city illustrates the central fact of the post-monarchical period: regardless of pre- Christian Edessa’s primary cultural orientation - whether it was to the East or to the West — the crucial factor in its later identity was its prominence as a center of Mesopotamian Christianity - the ‘First Christian Kingdom’ or the ‘Blessed City' - and it was this factor that preserved the name and status of Edessa through the Byzantine

- Verheyden, Joseph (2015-08-13). The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Apocrypha. OUP Oxford. pp. 104–5. ISBN 9780191080173.

The Letters of Jesus and Abgar. In the canonical Gospels, Jesus is depicted writing nowhere except in the sand, in the story of the woman taken in adultery; and the status of that story, usually printed in modern bibles at John 7.53-8.11, is itself disputed. However, according to Eusebius and later authors, Jesus wrote to Abgar, King of Edessa, in response to a letter that Abgar had sent to him. Eusebius’s account is found in his Ecclesiastical History 1.13,2.1.6-8, where he presents both letters and explains how Edessa was converted to Christianity when Abgar was healed by the apostle Thaddaeus, whose journey to Edessa after Jesus’ resurrection fulfilled Jesus’ promise in his letter that he would send one of his disciples to Abgar. The legend also exists in other versions; in the Syriac Doctrina Addai (the Syriac equivalent for Thaddeus) the story is told without reference to any letter of Jesus to Abgar. Abgar’s letter to Jesus and Jesus’ letter to Abgar may be found in the standard editions and translations of Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, and also in standard collections of apocryphal texts in translation such as Schnecmelcher (Drijvers 1991) and Elliott (1999).

- Lieu, Judith; North, John; Rajak, Tessa (2013-04-15). The Jews Among Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781135081881.

Eusebius tells us that he translated the correspondence from Syriac into Greek from a Syriac original from the royal archives at Edessa.

- King, Daniel (2018-12-12). The Syriac World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317482116.

The existence of both local chronicles is probably due to the high reputation of the archives held at Edessa. These were made famous by the reference in Eusebius to his use of the archives to discover the Abgar Legend. Whether or not Eusebius's claims were true, they were credible and stimulated the deposition of further documents, which would constitute raw material for the writing of local history (Segal 1970: 20–1).

- Petrosova, Anna (2005). The Armeniad: Visible Pages of History. Linguist Publishers. p. 146.

Eusebius of Caesarea discovered two letters in the archive of Edessa, written during the last year of Jesus' life.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2010-12-15). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444392548.

- Keith, Chris (2011-09-15). Jesus' Literacy: Scribal Culture and the Teacher from Galilee. A&C Black. p. 157. ISBN 9780567119728.

The Abgar Legend, in which Jesus sends a letter to King Abgar of Edessa, appears in Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History (ca. 325 C.E.) and is the center of the early fifth-century Syriac Doctrina Addai.

- Stillwell, Richard (2017-03-14). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781400886586.

Only one copy (in Greek) was found there of the legendary letter from Jesus to Abgar of Edessa.

- Wilfong, Terry G.; SULLIVAN, KEVIN P. (2005). "The Reply of Jesus to King Abgar: A Coptic New Testament Apocryphon Reconsidered (P. Mich. Inv. 6213)". The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists. 42 (1/4): 107–123. ISSN 0003-1186. JSTOR 24519525.

- Gottheil, R. J. H. (1891). "An Arabic Version of the Abgar-Legend". Hebraica. 7 (4): 268–277. doi:10.1086/369136. ISSN 0160-2810. JSTOR 527236.

- Walsh, Michael J. (1986). The triumph of the meek: why early Christianity succeeded. Harper & Row. pp. 125. ISBN 9780060692544.

The story about this kingdom which Eusebius relates is as follows. King Abgar (who ruled from AD 13 to 50) was dying. Hearing of Jesus' miracles he sent for him. Jesus wrote back - this correspondence, Eusebius claims, can be found in the Edessan archives - to say that he could not come because he had been sent to the people of Israel, but he would send a disciple later. But Abgar was already blessed for having believed in him.

- In his Church History, I, xiii, ca AD 325.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie ecclésiastique de l'Empire byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines. p. 172.

- Norris, Steven Donald (2016-01-11). Unraveling the Family History of Jesus: A History of the Extended Family of Jesus from 100 Bc Through Ad 100 and the Influence They Had on Him, on the Formation of Christianity, and on the History of Judea. WestBow Press. ISBN 9781512720495.

- Leclercq, Henri (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250101.htm

- Bernard, John. "The Pilgrimage of Egeria". University of Pennsylvania. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Forgery and Counterforgery, pp455-458

- S.K. Ross, Roman Edessa. Politics and Culture in the Eastern Fringe of the Roman Empire, Routledge, London 2001, p. 135

- Burkitt, F. C., Early Eastern Christianity, John Murray, London 1904, chap. I

- Adler, William (2011). "Christians and the Public Archive". In Mason, E.F. (ed.). A Teacher for All Generations: Essays in Honor of James C. VanderKam. Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism. Brill. p. 937. ISBN 978-90-04-22408-7. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Bauer 1971, Chapter 1.

- http://newadvent.org/fathers/0859.htm

- Camplani 2009, p. 253.

- Histoire du roi Abgar et de Jésus, Présentation et traduction du texte syriaque intégral de la Doctrine d’Addaï par. A. Desreumaux, Brepols, Paris 1993.

- M. Illert (ed.), Doctrina Addai. De imagine Edessena / Die Abgarlegende. Das Christusbild von Edessa (Fontes Christiani, 45), Brepols, Turhout 2007

- S.P. Brock, Eusebius and Syriac Christianity, in H.W. Attridge-G. Hata (eds.), Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism, Brill, Leiden-New York-Köln 1992, pp. 212-234, republished in S. Brock, From Ephrem to Romanos. Interactions between Syriac and Greek in Late Antiquity (Variorum Collected Studies Series, CS644), Ashgate/Variorum, Aldershot-Brookfield-Singapore- Sydney 1999, n. II.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2003). "The Doctrina Addai as a Paradigm of Christian Thought in Edessa in the Fifth Century". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 6 (2): 269–292. ISSN 1097-3702. Archived from the original on 21 August 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Mirkovic 2004.

- Camplani 2009.

- Griffith 2003, §3 and §28.

- Mirkovic 2004, pp. 2-4.

Sources

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bauer, Walter (1971). Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 25 January 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (German original published in 1934)

- Camplani, Alberto (2009). "Traditions of Christian foundation in Edessa: Between myth and history" (PDF). Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni (SMSR). 75 (1): 251–278. Retrieved 25 January 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Henry Palmer (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisenman, Robert (1992), "The sociology of MMT and the conversions of King Agbarus and Queen Helen of Adiabene" (PDF), Paper presented at SBL conference, retrieved 21 March 2017CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisenman, Robert (1997). "Judas the brother of James and the conversion of King Agbar". James the Brother of Jesus.

- Holweck, F. G. (1924). A biographical dictionary of the saints. St. Louis, MO: B. Herder Book Co.

- Mirkovic, Alexander (2004). Prelude to Constantine: The Abgar tradition in early Christianity. Arbeiten zur Religion und Geschichte des Urchristentums. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Tischendorf, Constantin. "Acta Thaddei (Acts of Thaddeus)". Acta apostolorum apocr. p. 261ff.

- Wilson, Ian (1991). Holy faces, secret places.

External links

- Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. VIII: Acts of the Holy Apostle Thaddeus, One of the Twelve

- Epistle of Jesus Christ to Abgarus King of Edessa from Eusebius

- Correspondence between Abgarus Ouchama, King of Edessa, and Jesus of Nazareth (J.Lorber, 1842)

- English translation of ancient documents on the conversion of Abgar, including relevant passages from Eusebius and the Doctrine of Addai are available in Cureton, W. (1864). Ancient Syriac documents. London, UK: Williams and Norgate. p. 1–23. Retrieved 15 June 2017.