Abbott Papyrus

The Abbott Papyrus serves as an important political document concerning the tomb robberies of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom. It also gives insight into the scandal between the two rivals Pawero and Paser of Thebes.

| The Abbott Papyrus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Papyrus |

| Writing | Hieratic |

| Period/culture | Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt |

| Place | Thebes, Egypt |

| Present location | G63/14, British Museum, London |

| Identification | 10221 |

The Abbott Papyrus is held and preserved at the British Museum under the number 10221.[1] The original owner/finder of the papyrus is unknown, but it was bought in 1857 from Dr. Henry William Charles Abbott of Cairo, hence the name Abbott Papyrus.[2]

The Abbott Papyrus dates back to the Twentieth Dynasty, around 1100 BC under the reign of Ramesses IX in his 16th year. According to T. Eric Peet, the papyrus’ content takes place in a four-day period from the 18th to the 21st of the third month of the inundation season, Akhet.[3]

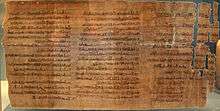

The Abbott Papyrus is 218 centimetres (86 in) in width and 42.5 centimetres (16.7 in) in height. It is written in hieratic. The main document consists of seven pages on the recto side, and on the verso side there are two lists of thieves, which have been called the Abbott dockets. The document is in great condition.[4]

Content

The Abbott Papyrus deals with the tomb robberies, but the underlying puzzle is the scandal between two rivals, Paser, the mayor of the East Bank of Thebes and Pawero, the mayor of the West Bank of Thebes, and according to Peet, it was written from the point of view of Pawero. As stated above, the content of the Abbott Papyrus is broken down into descriptions of events in a four-day time period from the 18th to the 21st of the third month of the inundation period during the 16th year of Ramesses IX’s reign.

On the 18th day, the Abbott Papyrus describes a search of the tombs claimed by Pawero to be violated. The commission searched ten royal tombs, four tombs of the Chantresses of the Estate of the Divine Adoratrix, and finally the tombs of the citizens of Thebes. The result of the search is the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II, two out of the four tombs of the Chantresses of the Estate of the Divine Adoratrix, and all of the citizen tombs were disturbed.[5][6]

On the 19th day, the Abbott Papyrus states that there was another search of tombs in the Valley of the Queens and the tomb of Queen Isis. The ones in charge of conducting the search brought with them a coppersmith named Peikharu from the Temple of Usimare Meriamun (Medinet Habu), who confessed in year 14 to stealing from the tomb of Isis and tombs from the Valley of the Queens. While searching, the coppersmith could not point to the tombs he violated, even after being brutally beaten. The rest of the day was spent searching the tombs, and the results showed that none of the tombs were vandalized. Also on the 19th day, there was a celebration for the tombs being undisturbed. Paser believed and stated to officials that the celebration was a direct aim at him, and he was going to report to the Pharaoh five charges against them.[7][8]

On the 20th day, the Abbott Papyrus describes a conversation between Pawero and the vizier Khaemwaset. The conversation ended in an investigation into the five charges claimed by Paser.[9][10]

On the 21st day, the Great Court of Thebes convened. After examining the charges made by Paser about the 19th and questioning the coppersmith, Paser is discredited.[11][12]

Connections

The Abbott Papyrus is important in the grand scheme of political trials dealing with tomb robberies. The Abbott Papyrus with relation to the Amherst Papyrus helps to form a more complete picture of the tomb robberies of the twentieth dynasty under Ramesses IX. The Abbott Papyrus connects with the Amherst Papyrus through the tomb of King Sobekemsaf. In the Abbott Papyrus, the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II was investigated and found vandalized. The Amherst Papyrus records the confession of thieves charged with vandalizing the tomb of King Sobekemsaf.[13]

The second connection also deals with tomb robberies and is made between the Abbott Dockets and a later series of tomb robbery trials which took place during the first two years of the era known as the Whm Mswt. From this era, which started in year 19 of the reign of Ramesses XI, several tomb-robbery papyri have survived, most notably: Papyrus Mayer A, Papyrus B.M. 10052, and Papyrus B.M. 10403. The list of thieves in the Abbott dockets foreshadows two trials described in Papyrus Mayer A. The first trial foreshadowed from the Abbot Dockets in Papyrus Mayer A is the trial concerning the thieves of the tombs of Ramesses II and Seti I. The other trial connection deals with thefts from tombs in the Necropolis of Thebes. The connection of the Abbott dockets with Papyrus B.M 10052 also deals with the trial of the thefts in the tombs of Thebes, but deals with information leading up to the trials. Lastly, the connection with the Abbott dockets and the Papyrus B.M 10403 deals again with trial of the thefts in the tombs of Thebes, but Papyrus B.M 10403 gives more detail on the evidence.[14]

Theories

There are many scholars who examine the Abbott Papyrus, but one of the first is T.E. Peet. Many scholars have developed theories concerning the Abbott Papyrus.

One theory is by Winlock; he argues that the commission sent to inspect the tombs went from north to south, which means the tombs of the kings are found and sited in the same direction.[15]

A second theory is by Peet, and he believes that the final reports made from commission were tainted on the 19th because a year later the tomb of Queen Isis was found violated.[16]

The final theory relates to Peet’s theory. The theory was developed by J. Capart, A.H. Gardiner, and B. Van de Walle. They first believe that the papyrus is a trustworthy historical account, but their main theory is that the Papyrus Leopold II is the exact counterpart to the Abbott Papyrus. They proved the theory true in the postscript of their document when the team examined the Abbott Papyrus and Papyrus Leopold II. They found that both papyri were the same height and length. Both the papyri also were written in the same script.[17]

See also

References

- “The Abbott Papyrus,” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aes/t/the_abbott_papyrus.aspx

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997), 28.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim 1997), 30.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997), 28-29.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997),30.

- A.J.Peden, Egyptian Historical Inscriptions of the Twentieth Dynasty. (2004), 228-233. p.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim 1997),30-31.

- A.J. Peden Egyptian Historical Inscriptions of the Twentieth Dynasty. (2004), 233-237.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997),31.

- A.J. Peden, Egyptian Historical Inscriptions of the Twentieth Dynasty. (2004),237-241.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997), 34-36.

- A.J. Peden, Egyptian Historical Inscriptions of the Twentieth Dynasty. (2004), 241-243.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997),28.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997), 128.

- Alan H.Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs: an Introduction. (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1961) 162-164.

- T.E. Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. (New York: Hildesheim, 1997) 36-37.

- J. Capart, A H Gardiner, B van de Walle. “New Light on the Ramesside Tomb-Robberies.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 22, no. 2 (1936): 189-193.

Further reading

- “The Abbott Papyrus,” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aes/t/the_abbott_papyrus.aspx

- Capart, J., A H Gardiner, B van de Walle. “New Light on the Ramesside Tomb-Robberies.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 22, no. 2 (1936): 169-193.

- Gardiner, Alan H. Egypt of the Pharaohs: an Introduction. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961.

- Peden, A.J. Egyptian Historical Inscriptions of the Twentieth Dynasty. 2004

- Peet, T. E., The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty. New York: Hildesheim, 1997.