Fluorenylidene

9-Fluorenylidene is an aryl carbene derived from the bridging methylene group of fluorene. Fluorenylidene has the unusual property that the triplet ground state is only 1.1 kcal/mol (4.6 kJ/mol) lower in energy than the singlet state.[1] For this reason, fluorenylidene has been studied extensively in organic chemistry.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

fluorene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C13H8 | |

| Molar mass | 164.207 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

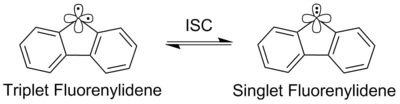

Fluorenylidene is a reactive intermediate. Reactions involving fluorenylidene proceed through either the triplet or singlet state carbene, and the products formed depend on the relative concentration of spin states in solution, as influenced by experimental conditions.[2] The rate of intersystem crossing is determined by the temperature and concentration of specific spin-trapping agents.[1]

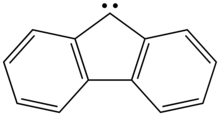

Structure

The ground state is believed to be a bent triplet, with two orthogonal sp hybrid orbitals singly occupied by unpaired spins.[3][4] One electron occupies an orbital of sigma symmetry in the plane of the rings, while the other occupies an orbital of pi symmetry, which interacts with the pi systems of the adjacent aromatic rings (delocalization into the rings is minimal, since zero-field parameter D is high).[5] The zero field splitting parameters predict a bond angle greater than 135°, and since the ideal bond geometry for cyclopentane carbons is about 109°, considerable ring strain causes the methylene sigma bonds to be bent.[5] In the singlet state, the spin-paired electrons occupy the sp2 hybrid orbital, orthogonal to an empty p-orbital.[6] Conversion of singlet to triplet fluorenylidene is achieved through intersystem crossing (ISC).

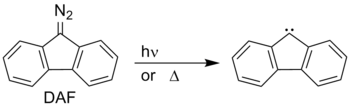

Generation of Fluorenylidene

Fluorenylidene can be produced by photolysis of 9-diazofluorene (DAF).

Ultra-fast (300 fs) time resolved laser-flash photolysis of DAF implicates a four-step process in the formation of fluorenylidene by irradiation of 9-diazofluorene.[7]

- Irradiation of DAF initially yields an excited singlet state diazofluorene molecule ( 1DAF*)

- 1DAF* decays to form the open shell carbene,1FL*, as the minor product, and the less energetic closed shell carbene, 1FL, as the major product.

- Any excited singlet 1FL* in solution relaxes to the lower energy singlet state 1FL (20.9 ps)

- 1FL equilibrates with the ground state triplet 3FL by intersystem crossing.

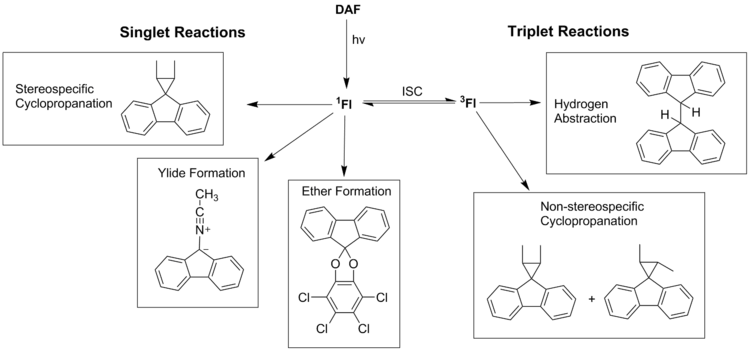

Reaction of Fluorenylidene in Solution

Fluorenylidene reacts with olefins as predicted by the Skell-Woodworth rules.[8] The stereochemistry of cycloaddition products depends on the relative rates of cyclopropanation (or other reactions) and intersystem crossing.[9] Stabilization of specific spin states, and, by extension, increased stereospecificity can be achieved by using solvents of different polarities .

Triplet Fluorenylidene Reactivity

Triplet fluorenylidene reacts with olefins in a stepwise fashion to produce a racemic mixture, provided that the rate of spin inversion (intersystem crossing) is not significantly faster than rates of intermediate bond rotation.[9]

Singlet Fluorenylidene Reactivity

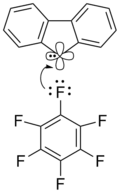

Singlet fluorenylidene reacts with olefins in a concerted fashion, maintaining the stereochemistry of the reactant olefin. Triplet quenchers such as butadiene solvents can be used to increase stereospecific yields.[9] Halogenated solvents also stabilize the singlet state.[2][7] For example, dibromomethane and hexafluorobenzene deactivate the higher-energy singlet state,[9] decelerating the rate of intersystem crossing in accordance with earlier studies of diphenylcarbene.[2] The mechanism of singlet state deactivation is theorized to occur through halogen-lone pair complexation of empty 1Fl P-orbitals.[7]

See also

References

- Grasse, P. B.; Brauer, B. E.; Zupancic, J. J.; Kaufmann, K. J.; Schuster, G. B. (1983). "Chemical and physical properties of fluorenylidene: equilibration of the singlet and triplet carbenes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 105 (23): 6833. doi:10.1021/ja00361a014.

- Sitzmann, E. V.; Langan, J. & Eisenthal, K. B. (1984). "Intermolecular effects on intersystem crossing studied on the picosecond timescale: the solvent polarity effect on the rate of singlet-to-triplet intersystem crossing of diphenylcarbene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 106 (6): 1868–1869. doi:10.1021/ja00318a069.

- Trozzolo, A. M.; Murray, R. W.; Wasserman, E. (1962). "The Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Phenylmethylene and Biphenylenemethylene; A Luminescent Reaction Associated With a Ground State Triplet Molecule". Communications to the Editor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. (84): 4990. doi:10.1021/ja00883a082.

- Moritani Ichiro; Murahashi Shun-Ichi; Yoshinaga Kunio; Ashitaka Hidetomo (1967). "10, 11-Dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a, d]cycloheptenylidene". Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 40: 1506. doi:10.1246/bcsj.40.1506.

- Leffler, John E. (1993). An Introduction to Free Radicals. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-59406-2.

- Isaacs, Neil S. (1974). Reactive intermediates in organic chemistry. London: Wiley. ISBN 9780471428619.

- Wang, J.; Kubicki, J.; Hilinski, E. F.; Mecklenburg, S. L.; Gustafson, T. L. & Platz, M. S. (2007). "Ultrafast study of 9-diazofluorene: Direct observation of the first two singlet states of fluorenylidene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (44): 13683–13690. doi:10.1021/ja074612w. PMID 17935331.

- Skell, P. S. & Woodworth, R. C. (1956). "Structure of Carbene, CH2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (17): 4496–4497. doi:10.1021/ja01598a087.

- CJ Moody; GH Whitham (1992). Reactive Intermediates. Oxford University Press.