6-j symbol

Wigner's 6-j symbols were introduced by Eugene Paul Wigner in 1940 and published in 1965. They are defined as a sum over products of four Wigner 3-j symbols,

The summation is over all six mi allowed by the selection rules of the 3-j symbols.

They are closely related to the Racah W-coefficients, which are used for recoupling 3 angular momenta, although Wigner 6-j symbols have higher symmetry and therefore provide a more efficient means of storing the recoupling coefficients.[1] Their relationship is given by:

Symmetry relations

The 6-j symbol is invariant under any permutation of the columns:

The 6-j symbol is also invariant if upper and lower arguments are interchanged in any two columns:

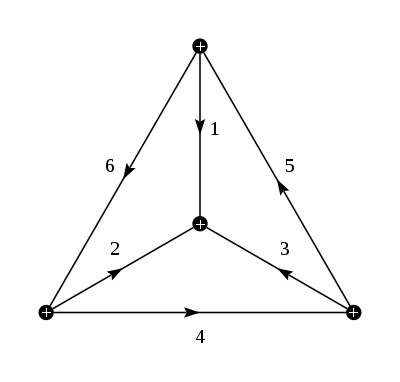

These equations reflect the 24 symmetry operations of the automorphism group that leave the associated tetrahedral Yutsis graph with 6 edges invariant: mirror operations that exchange two vertices and a swap an adjacent pair of edges.

The 6-j symbol

is zero unless j1, j2, and j3 satisfy triangle conditions, i.e.,

In combination with the symmetry relation for interchanging upper and lower arguments this shows that triangle conditions must also be satisfied for the triads (j1, j5, j6), (j4, j2, j6), and (j4, j5, j3). Furthermore, the sum of each of the elements of a triad must be an integer. Therefore, the members of each triad are either all integers or contain one integer and two half-integers.

Special case

When j6 = 0 the expression for the 6-j symbol is:

The triangular delta {j1 j2 j3} is equal to 1 when the triad (j1, j2, j3) satisfies the triangle conditions, and zero otherwise. The symmetry relations can be used to find the expression when another j is equal to zero.

Orthogonality relation

The 6-j symbols satisfy this orthogonality relation:

Asymptotics

A remarkable formula for the asymptotic behavior of the 6-j symbol was first conjectured by Ponzano and Regge[2] and later proven by Roberts.[3] The asymptotic formula applies when all six quantum numbers j1, ..., j6 are taken to be large and associates to the 6-j symbol the geometry of a tetrahedron. If the 6-j symbol is determined by the quantum numbers j1, ..., j6 the associated tetrahedron has edge lengths Ji = ji+1/2 (i=1,...,6) and the asymptotic formula is given by,

The notation is as follows: Each θi is the external dihedral angle about the edge Ji of the associated tetrahedron and the amplitude factor is expressed in terms of the volume, V, of this tetrahedron.

Mathematical interpretation

In representation theory, 6-j symbols are matrix coefficients of the associator isomorphism in a tensor category.[4] For example, if we are given three representations Vi, Vj, Vk of a group (or quantum group), one has a natural isomorphism

of tensor product representations, induced by coassociativity of the corresponding bialgebra. One of the axioms defining a monoidal category is that associators satisfy a pentagon identity, which is equivalent to the Biedenharn-Elliot identity for 6-j symbols.

When a monoidal category is semisimple, we can restrict our attention to irreducible objects, and define multiplicity spaces

so that tensor products are decomposed as:

where the sum is over all isomorphism classes of irreducible objects. Then:

The associativity isomorphism induces a vector space isomorphism

and the 6j symbols are defined as the component maps:

When the multiplicity spaces have canonical basis elements and dimension at most one (as in the case of SU(2) in the traditional setting), these component maps can be interpreted as numbers, and the 6-j symbols become ordinary matrix coefficients.

In abstract terms, the 6-j symbols are precisely the information that is lost when passing from a semisimple monoidal category to its Grothendieck ring, since one can reconstruct a monoidal structure using the associator. For the case of representations of a finite group, it is well-known that the character table alone (which determines the underlying abelian category and the Grothendieck ring structure) does not determine a group up to isomorphism, while the symmetric monoidal category structure does, by Tannaka-Krein duality. In particular, the two nonabelian groups of order 8 have equivalent abelian categories of representations and isomorphic Grothdendieck rings, but the 6-j symbols of their representation categories are distinct, meaning their representation categories are inequivalent as monoidal categories. Thus, the 6-j symbols give an intermediate level of information, that in fact uniquely determines the groups in many cases, such as when the group is odd order or simple [5].

Notes

- Rasch, J.; Yu, A. C. H. (2003). "Efficient Storage Scheme for Pre-calculated Wigner 3j, 6j and Gaunt Coefficients". SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 25 (4): 1416–1428. doi:10.1137/s1064827503422932.

- Ponzano G and Regge T (1968). "Semiclassical Limit of Racah Coefficients". in Spectroscopy and Group Theoretical Methods in Physics: Amsterdam: 1–58. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Roberts J (1999). "Classical 6j-symbols and the tetrahedron". Geometry and Topology. 3: 21–66. arXiv:math-ph/9812013. doi:10.2140/gt.1999.3.21.

- Etingof, P.; Gelaki S.; Nikshych D.; Ostrik V. (2009). Tensor Categories (PDF).

- Etingof, P.; Gelaki S. (2000). "Isocategorical Groups". arXiv:math/0007196.

References

- Biedenharn, L. C.; van Dam, H. (1965). Quantum Theory of Angular Momentum: A collection of Reprints and Original Papers. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-096056-7.

- Edmonds, A. R. (1957). Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07912-9.

- Condon, Edward U.; Shortley, G. H. (1970). "Chapter 3". The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09209-4.

- Maximon, Leonard C. (2010), "3j,6j,9j Symbols", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248

- Messiah, Albert (1981). Quantum Mechanics (Volume II) (12th ed.). New York: North Holland Publishing. ISBN 0-7204-0045-7.

- Brink, D. M.; Satchler, G. R. (1993). "Chapter 2". Angular Momentum (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-851759-9.

- Zare, Richard N. (1988). "Chapter 2". Angular Momentum. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 0-471-85892-7.

- Biedenharn, L. C.; Louck, J. D. (1981). Angular Momentum in Quantum Physics. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-13507-8.

External links

- Regge, T. (1959). "Simmetry Properties of Racah's Coefficients". Nuovo Cimento. 11 (1): 116–117. Bibcode:1959NCim...11..116R. doi:10.1007/BF02724914.

- Stone, Anthony. "Wigner coefficient calculator". (Gives exact answer)

- Simons, Frederik J. "Matlab software archive, the code SIXJ.M".

- Volya, A. "Clebsch-Gordan, 3-j and 6-j Coefficient Web Calculator". Archived from the original on 2012-12-20.

- Plasma Laboratory of Weizmann Institute of Science. "369j-symbol calculator".

- GNU scientific library. "Coupling coefficients".

- Johansson, H.T.; Forssén, C. "(WIGXJPF)". (accurate; C, fortran, python)

- Johansson, H.T. "(FASTWIGXJ)". (fast lookup, accurate; C, fortran)