20th century road schemes in Bristol

Road building was central to planning policy for much of the 20th century in Bristol, England. The planned road network evolved over time but at its core was a network of concentric ring (or circuit) roads and high-capacity radial roads.

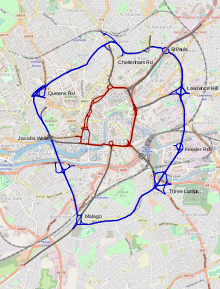

The Inner Circuit Road formed a ring around Bristol's central area and was completed in 1970. The Outer Circuit Road was intended to form an outer ring concentric with this, but the only substantial part to be completed was the 1.3km-long Easton Way. The two ring roads were to be complemented by 8 radial roads, some of which would follow new routes while others would be made by widening existing roads.

These schemes had for the most part been abandoned by the early 1990s, and subsequently much of what was built has been decommissioned.[1]

Planning and construction

The inter-war period was one of rapid growth in Bristol, with 22,000 private homes and 12,000 council houses being built around the city. In addition, Bristol was at the focus of a number of through routes, with growing volumes of traffic concentrated into a highly constrained area in the city centre. To address this, in 1923 the city council set up a town planning committee chaired by B F Brueton, which developed into the Bristol and Bath and District Joint Regional Planning Committee. Brueton co-authored Sir Patrick Abercrombie's 'Bristol and Bath Regional Planning Study' of 1928, out of which the plan to ease Bristol's traffic congestion using concentric ring roads grew.[2]

Inner Circuit Road (A4044)

The Inner Circuit Road was intended as a primary distributor road for local traffic in the central area of Bristol. Construction started in 1936 with the laying out of Temple Way and Redcliffe Way,[3] and by 1937 the dual carriageway of Redcliffe Way had been cut diagonally through Queen Square leaving the Rysbrack statue of William III stranded on a traffic island and, ironically, requiring the demolition of the City Engineer's offices at No.63.[4][5] At The Centre, construction of a culvert to cover over the River Frome and accommodate the new road was underway, and at Redcliff Backs a bascule bridge was being built. Work continued despite the outbreak of World War II, and by the end of 1940 the Inner Circuit Road was largely complete from The Centre to Temple Way.[6] Further developments were suspended for the duration of the war.

Construction work restarted in the early 1960s with Phase 3 from St James Barton to Wellington Road. A 318m re-erectable flyover was constructed at Victoria St in 1967,[7] and the Temple Way Underpass was completed in 1968. By 1970, with the construction of the last few links at Lewins Mead and Rupert St, the Inner Circuit Road formed a complete 3.4km ring.

The later phases of the Inner Circuit Road, from Old Market to the northern end of The Centre, attempted to vertically segregate pedestrians from motor traffic. At Old Market roundabout, escalators led up to a system of bridges and decks leading through to Castle Park; a similar elevated pedestrian system was partially completed at Lewins Mead and Rupert Street, whilst at St James Barton pedestrians were consigned below the roads in what became known as the Bear Pit.[3] This vertical segregation infrastructure, consisting largely of unattractive concrete steps and walkways with poor accessibility, was never popular with pedestrians and much of it has subsequently been removed.

Outer Circuit Road (A4320)

Bristol's post-war development plan of 1952 contained plans for an Outer Circuit Road forming a circuit of Bristol's inner suburbs.[3] These were refined following an origin and destination study conducted in 1963 and published, together with plans for eight enhanced radial routes, in the Bristol City Centre Policy Report of 1966.[8] The Outer Circuit Road was designed to take long-distance through traffic as well as local cross-city traffic, thus allowing the Inner Circuit Road to fulfil its intended function as a purely local distributor road. Although it was proposed to build the Outer Circuit Road as a free-flowing two-lane dual carriageway of urban motorway standard, it was nonetheless anticipated that by 2010 some sections, such as Cheltenham Road to the M32, would be operating at capacity. Therefore, the 1966 report proposed that the road would have to be widened to three-lane dual carriageway along its entire length, and that five of the junctions with the main radial roads would need to be grade separated.[8]

The development plan for the Outer Circuit Road obtained ministerial approval in 1969.

Whilst the route of the Inner Circuit Road passed through mostly commercial property, the Outer Circuit Road's route required large-scale demolition in residential suburbs. Construction was to be phased, starting with the section through Easton from the M32 to Lawrence Hill. This was an area which was already undergoing redevelopment and traffic forecasts suggested that this part of the route was most needed.[9] It also passed through an area where property was cheap, the topography was straightforward, and local opposition was poorly organised.[10]

Opposition grew as more people became aware of what was planned. In Clifton, Cotham and Montpelier the topography was more difficult and local opposition was wealthier and more articulate. A Campaign against the Outer Circuit Road was established, and begun to put pressure on the Secretary of State and local politicians. Despite this, construction of Easton Way was completed, and in steeply-hilled picturesque Totterdown more than 500 terraced Victorian houses and businesses were demolished in preparation for a huge new roundabout that was never built.

By the early 1970s, public opinion of urban roadbuilding had changed and pressure groups were starting to have an impact; but more than anything it was the economic climate that halted development.[10]

A38 St James Barton to Cheltenham Road

The 1966 report proposed to widen this route to form a two-lane dual carriageway, with an almost continuous central reservation to restrict right-hand turns. Following the enlargement of St James Barton Roundabout to form today's Bear Pit, a second phase of construction would have seen this roundabout replaced by a two-way underpass connecting North Street (the southern extension of Stokes Croft) with the north-west section of the Inner Circuit Road, leading towards The Centre. At the northern end of Cheltenham Road, a two-level interchange would connect with the Outer Circuit Road using Cotham Hill and new link roads near Arley Hill and Station Road.[8]

With the exception of the Full Moon, a 17th-century coaching inn,[11] all properties on North Street were demolished for the construction of this road and its junction at St James Barton. Post-war reconstruction on Stokes Croft was set back behind a generous road widening line.

M32 (The Parkway)

The M32 forms the main link between central Bristol and the M4 and M5 motorways. Its construction in the 1970s involved the destruction of historic parkland at Stoke Park and a large railway viaduct at Muller Road, and at its southern end extensive demolition was required. However, as with Easton Way this was linked with redevelopment and 'slum clearance'. Several streets of Georgian properties, some listed, were cleared for Newfoundland Way which formed the final link from St Pauls Roundabout to the Inner Circuit Road at Bond Street.[12]

The M32 is an overwhelming barrier to mobility and accessibility for residents of St Pauls and Easton, with the main links between the areas consisting of grade-separated dual carriageway intersections and narrow footbridges crossing the motorway at a dizzying height.[13]

A420 Old Market Street and Lawrence Hill

In the 1966 report, a three-lane dual-carriageway road was planned to replace the West Street one-way system, giving a direct high-capacity link between the Inner Circuit Road at Temple Way and the Outer Circuit Road at Easton Way.[8] These plans heralded decades of planning blight in Old Market Street and West Street.

A4 Bath Road and A37 Wells Road

The A4 from its junction with the Inner Circuit Road to its junction with the Outer Circuit Road and the A37 Wells Road in Totterdown was to become a three-lane dual carriageway. At Victoria Street the junction would be developed in stages, starting with a temporary flyover linking Temple Way with Redcliffe Way, and ultimately becoming a multi-level interchange. The original Bath Bridge would be replaced with a new span to the east, allowing for a flyover across Bath Bridge Roundabout for through traffic. At Three Lamps, space was made available to accommodate a large junction connecting the A37, A4 and Outer Circuit Road. Again it was intended that the junction could be expanded as demand increased.[8]

A38 Redcliff Hill and Bedminster By-Pass

Properties on Redcliff Hill, including the historic Redcliffe Shot Tower, were demolished in 1968 to make way for the northern end of a proposed dual carriageway connecting with the A38 south-west of Bedminster. The new route was to be an elevated road running in a straight line parallel to East St and West St, crossing under the Bristol to Exeter railway west of Bedminster Station, then continuing to a flyover intersection with Outer Circuit Road at Sheene Road before joining the A38 at Bridgwater Rd near its junction with Bishopsworth Rd.[8]

This road formed part of a comprehensive redevelopment scheme for Bedminster, which included Dalby Avenue (built as a by-pass for East Street) and the Outer Circuit Road.[14] Although many properties were demolished, no significant construction of the by-pass took place south of Bedminster Bridge. Windmill Hill City Farm was set up in 1976 on land cleared as part of this scheme.[15][16]

For nearly 20 years, the link from Bedminster Bridge Roundabout to Bedminster Parade was known as 'Wixon's Kink' due to its sharp deviation around the premises of Wixon's ladies underwear shop. The proprietor, Edward Wixon, was frustrated after being asked to vacate the premises just one month after relocating there, and refused to move.[17]

A370 Coronation Road/Cumberland Road and Cumberland Basin Interchange

The 1966 City Centre Policy Report proposed that the A370 west of Bath Bridge would be routed along either side of the New Cut, with incoming traffic using Cumberland Road, Commercial Road and Clarence Road on the north bank while outgoing traffic was to use York Road and Coronation Road on the south bank. Wapping Road was to be widened to 36 feet (11 m), to link with the Inner Circuit Road at The Grove.[8]

Georgian houses along York Road were acquired and became derelict in anticipation of widening this route, but were eventually restored after the project was cancelled.

The route had changed significantly by 1972 when the Casson Conder report was published. The eastern terminus of the road had become a new large free-flow junction with the Outer Circuit Road, by then diverted to the east of its 1966 proposed alignment. This junction, together with associated links to the Inner Circuit Road, would have consumed most of Spike Island to the immediate south and east of today's location of the SS Great Britain. The A370 was to cross the New Cut on a new bridge west of Sydney Row before connecting to its current route near Greville Smyth Park.[18]

Somerset County Council's County Development Plan of 1965 included a southern motorway link with Bristol, starting at Cumberland Basin and passing to the east and south east of Long Ashton before skirting the northern edge of Nailsea and connecting with the M5 motorway at junction 20. Although this scheme did not survive the 1974 local government reorganisation, the Long Ashton Bypass follows its route as far west as Flax Bourton.[19]

Cumberland Basin Interchange

Work on the Cumberland Basin flyover system started in 1962, with the demolition of houses in Brunswick Place (now the site of Bristol Gate) followed by the felling of trees in Ashton Park to make way for the approach road.[20] The interchange was opened in April 1965. The complexity of the intersection, due in part to its highly constrained site, led to its being the butt of jokes from the outset:

Hast seen our brand new bridge, up there in Cumberland Basin?

The cars go by like thunder, and up and round and under,

Where they goes, nobody knows, tain't no bleedin' wonder!

— Adge Cutler, Virtute et Industrial

Nominally a free-flow junction, the interchange links the A370 from the southwest with the A3029 (itself a link to the A38 at Bedminster) and the A4 Portway. Where the main flyover crosses the western end of Spike Island, slip roads connect to minor local roads leading to Cumberland Rd; these appear to have been intended to connect to the A370 through Spike Island. The legacy of this is that the area west of Avon Crescent contains a complex knot of roads which are largely redundant, and leave little room for anything else.

A4 The Centre to Hotwell Road

At the time of the 1966 report, the route of the A4 took it along the southern edge of College Green and thence to Hotwell Road via Deanery Road. A new route was proposed which would improve the environment of College Green by taking traffic through the then derelict area of Canon's Marsh (now known as Harbourside) on a one-way system using Anchor Road for inbound traffic and a new parallel road to its south for outbound traffic. At the eastern end of this road system, a new bridge would cross the Floating Harbour and link to The Grove at its junction with Prince Street; at the western end would be a multi-level junction with the Outer Circuit Road, Jacobs Wells Road, St Georges Road and Hotwell Road.[8]

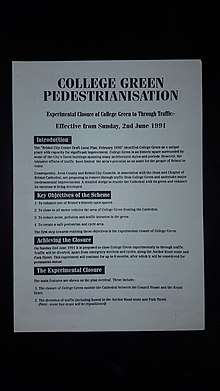

The road at the southern edge of College Green was closed in 1991, in a scheme which improved access to Anchor Road from The Centre.[21] The remaining elements of this plan were not implemented.

A4018 Park Street to Queens Road

The strategy for this route, given its role as an important shopping area, was to divert local through traffic away from it as far as practicable using the new road system in Canon's Marsh.

A4 (Portway)

The Portway was built to improve access between Avonmouth Docks and Bristol and was completed in 1926, thus predating the Abercrombie Report. The route follows the course of the River Avon from Cumberland Basin to Avonmouth, where it links with the M5 motorway.

Other routes

The remaining major routes out of Bristol were all subject to widening schemes. Any new development along these roads had to comply with set-back building lines referred to as road widening lines. These are still evident in places like Whiteladies Road where new buildings stand some 5-10 metres behind their older neighbours.[22]

Cancellation, alteration and extension

The social and environmental costs of building urban road schemes, together with the realisation that they did not deliver their anticipated benefits, meant that most of these schemes were never completed. By 1973 inflation, a collapse in the property market and changes in national policy halted spending on urban road schemes. By the time the economy had recovered in the late 1970s, the climate of opinion had changed: the primacy of the motor car was no longer assumed, and urban conservation gained importance when making planning decisions.[5][10]

This fundamental change is reflected in the Bristol Local Plan of 1992, which stated:

Opportunities for major new highways within the city, without significant disruption to the existing urban fabric, are extremely limited. Past experience shows that while they may relieve certain areas, the impact of any new road frequently spreads well beyond its immediate corridor and that without appropriate action can affect traffic in communities and areas some distance from the proposed road. The City and County Council believe that in general major new road construction is unlikely to address the city's current traffic problems...

College Green

Before 1991, the main route of the A4 between The Centre and Cumberland Basin passed along the south side of College Green, causing noise, pollution and traffic intrusion. In 1991 this route was closed and traffic was diverted onto Anchor Road. Although this scheme had some similarities to earlier proposals, it was much reduced in scale: access to Anchor Road from The Centre was improved, but it remained a two-lane road and none of the other through routes were built.[21]

Queen Square, Redcliffe Way and The Centre

By 1964 it was recognised that the alignment of Redcliffe Way past St Mary Redcliffe Church had damaged the setting of an important building, and a scheme to realign the road close to Portwall Lane was proposed. The scheme included an overpass for northbound traffic turning right from Redcliffe St onto Redcliffe Way, and a new enlarged roundabout to the north. This, together with the diversion of the dual carriageway which had disfigured Queen Square thirty years earlier, formed part of the Bristol City Centre Policy Report of 1966.[8] These plans assumed that the traffic would be diverted onto new urban motorways running through what is now known as Harbourside.

The completion of the M4 and M5 motorways meant that by the mid-1970s most long-distance through traffic bypassed Bristol, and from 1986 the Avon Ring Road diverted further traffic away from the central area. Plans were developed to downgrade Redcliffe Way, diverting traffic via Perry Road and Jacobs Wells Road to the north, and Coronation Rd to the south, effectively turning the Inner Circuit route into an elongated loop with Cumberland Basin at its western extremity. The dual carriageway across Queen Square was closed, at first experimentally, in 1992; Redcliffe Flyover was demolished in 1998 to be replaced with the Temple Circus Gyratory, which in turn was further simplified in 2017.[23][24] The road across Quay Head was removed during the 1998 remodelling of The Centre, effectively decommissioning the whole western half of the Inner Circuit Road.

Bond Street

Temple Way and Bond Street were diverted to the east of their original alignment at their junction with Newfoundland Way from 2005 onwards to accommodate Cabot Circus, an extension of the Broadmead shopping district.

St Philips Causeway

The Bristol Development Corporation, set up in 1989 to develop an area to the east of Temple Meads Station, had as a key objective the opening up of road links to derelict former railway land to the east of St Philip's Marsh.

The core of this plan was a new road, named St Philips Causeway but generally known as the Spine Road. This is a dual carriageway built largely on a viaduct, which initially follows the planned route of the Outer Circuit Road south from Lawrence Hill before turning south-east and connecting with Bath Road near Sandy Park Road. Controversially it made no provision for pedestrians or cyclists, though as a concession some unsatisfactory circuitous routes were signposted at ground level. After the Bristol Development Corporation was dissolved and control passed back to Bristol City Council, basic cycle and pedestrian facilities were added.

Future plans

Callington Road Link

The Callington Road Link is a proposed extension of St Philip's Causeway southwards along the course of the dismantled Bristol and North Somerset Railway to Callington Road, near the Tesco Extra supermarket. This scheme is supported by the West of England Joint Transport study, but opposed by others who think the route could be better used as an urban greenway.[25][26]

Western Harbour

In 2018 Bristol Mayor Marvin Rees announced plans to downgrade the 'heavy road infrastructure' of Cumberland Basin and replace it with a 'less high impact' option, releasing some 15-20 ha of developable land with potential for providing 3,500 homes.[27]

References

- Directorate of Planning and Development Services (1992). Draft Bristol Local Plan April 1992. Bristol City Council. p. 142. ISBN 0-900814-70-5.

- Hasegawa, Junichi (1992). "3 Bristol, Coventry and Southampton before the war". Replanning the blitzed city centre. Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15633-9.

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Pevsner Architectural Guides - Bristol. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0300104424.

- "City Engineer's Office, 63 Queen Square". Bristol Archives. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- David J Eveleigh. "Chapter Three - The City Centre". Britain in Old Photographs - Bristol 1920-1969. ISBN 9780750919074.

- Winstone, Reece (1980). Bristol in the 1940s. Reece Winstone Archive & Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 0-900814-61-6.

- "40 Years Ago: Relieving traffic congestion – re-erectable flyover at Bristol". newsteelconstruction.com. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Unwin, T.J.; Bennett, J.B. (1966). "17 Future Road Pattern". Bristol City Centre Policy Report 1966. City and County of Bristol.

- Winstone, John (1990). Bristol as it Was 1963 - 1975. Reece Winstone Archive & Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 0-900814-70-5.

- Priest, Gordon; Cobb, Pamela (1980). "Urban renewal". The Fight for Bristol. Bristol Civic Society and The Redcliffe Press.

- Historic England. "The Full Moon Public House (1282188)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Winstone, John (1995). Bristol as it Was 1976 - 1980. Reece Winstone Archive & Publishing. ISBN 0-900814-74-8.

- Rajé, Fiona (2017). "1.3 The transport policy environment: legacies and innovations". Transport, Demand Management and Social Inclusion - The Need for Ethnic Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 1351877690.

- "Bedminster Comprehensive Redevelopment Scheme". Bristol Archives. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "1950s Bristol Town Plans" (Map). 1950s Bristol Town Plans. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Humble Beginnings". Windmill Hill City Farm. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Bristol - Bedminster 6".

- "A Close Shave – a spaghetti junction in the city docks". Bristol Museums. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "South Bristol Spur – a pointless junction, a large gap and oddness". Pathetic Motorways. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Winstone, John (1990). Bristol as it Was 1963 - 1975. Reece Winstone Archive & Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 0-900814-70-5.

- Avon County Council (1991). College Green Pedestrianisation.

- Priest, Gordon; Cobb, Pamela (1980). "The 1970s: The growth of the amenity movement". The Fight for Bristol. Bristol Civic Society and The Redcliffe Press.

- "Temple Gate: the junction through the years". Bristol Temple Quarter Enterprise Zone. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Avon County Council and Bristol City Council (1992). Queen Square Experimental Closure to Through Traffic.

- "Old Brislington Railway – Relief Road or Green Haven?". Bristol Cycling. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "West of England Joint Transport Study: Transport Vision". Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol City, North Somerset, and South Gloucestershire. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Bristol Development and Investment Hotspots". Invest Bristol and Bath. Retrieved 11 April 2018.