1939 American Karakoram expedition to K2

The unsuccessful 1939 American Karakoram expedition to K2 was the second U.S. attempt on the unclimbed second-highest mountain in the world, following the 1938 reconnaissance expedition. Fritz Wiessner, the leader of the expedition, and Pasang Dawa Lama got to within 800 feet (240 m) of the summit of K2 via the Abruzzi Ridge – a difficult and arduous route – with Wiessner doing practically all the lead climbing. Through a series of mishaps one of the team members, Dudley Wolfe, was left stranded near the top of the mountain after his companions had descended to base camp. Three attempts were made to rescue Wolfe. On the second attempt three Sherpas reached him after he had been alone for a week at over 24,000 feet (7,300 m) but he refused to try to descend. Two days later the Sherpas again tried to rescue him but they were never seen again. A final rescue effort was abandoned when all hope for the four climbers had been lost.

.jpg)

The deaths and the apparently badly organized nature of the expedition led to considerable acrimony between team members and commentators back in America. At first most people blamed Wiessner but, after he published an article in 1956, criticism turned to one of the team, Jack Durrance. When Durrance at last made his manuscript expedition diary available in 1989 it seemed instead that the primary failings had been with the deputy leader, Tony Cromwell, as well as with Wiessner himself.

In 1961 Fosco Maraini described it as "one of the worst tragedies in the climbing history of the Himalaya".

Background

K2

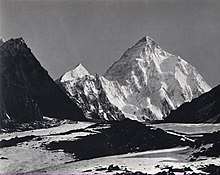

K2 is on the border between what in 1939 was the British Raj of India (now Pakistan) and the Republic of China. At 28,251 feet (8,611 m) it is the highest point of the Karakoram range and the second highest mountain in the world. From the beginning of the 20th century several unsuccessful attempts had been made to reach the summit and the 1909 Duke of the Abruzzi expedition reached about 20,510 feet (6,250 m) on the southeast ridge before deciding the mountain was unclimbable. This route later became known as the Abruzzi Ridge (or Abruzzi Spur) and eventually became regarded as the normal route to the summit.[1]

American Alpine Club 1938 expedition

At the American Alpine Club's 1937 meeting, Charlie Houston and Fritz Wiessner were the main speakers and Wiessner proposed an expedition to climb K2 for the first time, an idea that was strongly supported. The American Alpine Club (AAC) president applied for an expedition permit via the Department of State – the British colonial authorities approved the plan for an attempt in 1938 to be followed by another in 1939 if the first attempt failed. Although Wiessner had been expected to lead the first expedition, he backed down and suggested Houston replace him. Houston had considerable mountaineering experience – he had organized and achieved the first ascent of Alaska's Mount Foraker in 1934 and had been a climbing member on the British–American Himalayan Expedition of 1936 which reached the top of Nanda Devi, then the highest summit to have been climbed.[2]

Houston's expedition investigated several routes up the mountain and, after deciding on the Abruzzi Ridge, made good progress up to the head of the ridge at 24,700 feet (7,500 m) on July 19, 1938. However, by then their supply lines were very extended, they were short of food and the monsoon seemed imminent. It was decided that Houston and Paul Petzoldt would make a last push to get as close to the summit as they could and then rejoin the rest of the party in descent. On July 21 the pair reached about 26,000 feet (7,900 m). In favorable weather they were able to identify a suitable site for a higher camp and a clear route to the summit.[3]

The expedition was regarded as a success. A suitable route up the Abruzzi Ridge had been explored in detail, good sites for tents had been found (sites that would go on to be used in many future expeditions) and they had identified the technically most difficult part of the climb, up the House Chimney at 22,000 feet (6,700 m) (named after Bill House who had led the four-hour climb up the gully). The way was now clear for a 1939 expedition.[4]

Fritz Wiessner

Wiessner was a 39-year-old German rock climber who had achieved a huge number of climbing routes in the Alps, some of them outstanding first ascents. He was an astute businessman in the chemical industry and a visit to America in 1929 drew him into spending more, and then nearly all, his time there. In 1932 he joined an expedition to Nanga Parbat led by Willy Merkl. From their high point at 23,000 feet (7,000 m) Wiessner spotted K2 130 miles (210 km) away and the mountain became an obsession for him. Back in the United States Wiessner made friends with many influential and rich people and he introduced skiing and rock climbing techniques of a higher standard than those practised at that time in America. In 1935 he became a U.S. citizen and the next year he and Bill House became celebrated as the first people to climb Mount Waddington in Canada, a mountain on which there had previously been sixteen unsuccessful attempts. By 1938 he had become the pre-eminent American climber and, having been on Nanga Parbat, the only one with experience on an eight-thousand-metre peak. He seemed the obvious choice to lead the 1938 expedition for which he had led the successful attempts to secure funding. As it turned out he had prior commitments in 1938 but he was available for 1939.[5][6]

Preparation for 1939 expedition

| History of climbing K2 | |

|---|---|

Television programs | |

1939 expedition starts at 04:13 minutes | |

1939 expedition starts at 11:55 minutes |

Team members

In the fall of 1938, the American economy was not in good shape, and there were no realistic prospects for obtaining public or private funding for a 1939 expedition, so Wiessner had to choose a team from people who could pay their own expenses. The expedition would be away for up to six months, there were rather few accomplished mountaineers in America at the time, and none of the 1938 expedition members felt able to repeat their efforts. The people selected were going to be decided on grounds of availability, and ability to pay, rather than on mountaineering ability.[9][10] The total cost was estimated to be $17,500 (equivalent to US$252,857 in 2018), or $2,500 per person.[11]

Eventually, there were to be six members of the team, as well as nine Sherpas appointed in advance; porters were signed up en route. No mountaineers considered most-qualified were able to join the expedition. Tony Cromwell, appointed to be Wiessner's deputy, was wealthy enough not to need to be in employment, and was dedicated to mountaineering with more mountain ascents than anyone else in the AAC. He always employed mountain guides, and he was very much a follower on his mountain expeditions, which were not particularly challenging. He was 44, and had said that he would not be climbing high on K2. Chappell Cranmer (aged 20) was a student at Dartmouth College, and had been a climbing partner of Wiessner's earlier in 1938. He had done some mountaineering in the Rockies and rock climbing in New England. He had very limited experience, but did seem to have promise. George Sheldon, a classmate of Cranmer's, was very enthusiastic – the little experience he had had was in the Tetons.[12][13]

Dudley Wolfe, born 1896, was the son of a wealthy coffee merchant who had married the even-wealthier daughter of a silver baron. Turned down by the U.S. Army for war service, Wolfe joined the French Foreign Legion too late in the Great War to see action. He owned an immense and magnificent estate in Maine, from where he competitively sailed his various yachts. He had an interest in skiing and, later, mountaineering, though he frequently needed guides to haul him up. He was bulky and clumsy, but also strong, and easily tolerated arduous conditions.[13][14] Jack Durrance was appointed when a more experienced climber dropped out at the last minute, after Wiessner and Wolfe had already left for Europe. He was known to Cranmer and Sheldon through their shared Dartmouth connections. He was twenty-six, and his childhood had been spent in Bavaria, where he had learned skiing and rock climbing. Returning to the United States in 1935, he had become a mountain climber and guide in the Tetons. Although he had not started his medical training, he was appointed the official expedition doctor. He had little money, but some generous members of the AAC helped fund him. He considered himself under-qualified for the expedition and, in his personal diary, wrote that he thought the same of everyone else, save Wiessner.[15] Among those who had turned down their invitations were Bill House, Adams Carter, Sterling Hendricks, Roger Whitney, and Alfred Lindley – any of whom would have strengthened the team.[12][16][17] House later said his decision was due to personal differences with Wiessner.[17]

The non-climbing participants were to be met in Srinagar: Lieutenant George Trench, the British liaison and transport officer; Chandra Pandit, the interpreter; and Noor, the cook. Pasang Kikuli was sirdar, and the other Sherpas were Pasang Dawa Lama (deputy sirdar), Pasang Kitar, Pemba Kitar, Phinsoo, Tsering Norbu, Sonam (Pasang Kikuli's brother), Tse Tendrup, and Dawa Thondup.[18] Pasang Kikuli had been with Houston on the 1936 ascent of Nanda Devi, and was sirdar in 1938 on K2 – he was thus the most experienced climber in the world on high mountains.[19]

Equipment

Wiessner and Wolfe purchased mountaineering equipment in Europe where, in those days, there was a much wider choice than in America.[20] They bought the best available – Wolfe was paying most of the bills which were over and above the official expenses.[20][21] They obtained strong but heavy tents, inflatable mattresses, Primus stoves, nailed boots and eiderdown sleeping bags. They obtained the best ropes of the time made of Italian hemp which, being water absorbent, become heavy and almost impossible to manipulate when frozen. Dehydrated (not freeze-dried) food was very limited – milk and a few fruits and vegetables – and most food was canned, apart from pemmican. Padded clothes were not available, they failed to buy satisfactory boots or sleeping bags for the Sherpas and omitted to provide snow goggles for the porters. Short-range radios and supplementary oxygen systems were both available in 1939 but were unreliable and very heavy so they were not taken. Durrance's high-altitude boots were not delivered to him in time.[20] For the time they were well equipped with technical climbing equipment such as pitons, carabiners and crampons.[22]

Voyage out

-_Hafen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-23-151.jpg)

Durrance sailed to Germany and, after some skiing in Switzerland, went to Genoa where he boarded SS Conte Biancamano on March 29, 1939. He was there told that Vittorio Sella, a veteran of the 1909 Abruzzi expedition and now the grand old man of mountain photography, was asking to meet members of the expedition. While they were talking Wiessner and Wolfe turned up and Wiessner was visibly upset – the intention had been that he, Wiessner, would greet Sella first. Durrance felt slighted and later said he would have returned home if he had the money. At Naples, Cranmer, Cromwell and Sheldon joined the ship and a spirit of comradeship was regained. They travelled first-class in style[note 3] arriving in Bombay on April 10 from where they took a forty-hour train journey to Rawalpindi. In two cars they drove 180 miles (290 km) to Srinagar in the Vale of Kashmir.[24]

Srinagar and Vale of Kashmir

At Srinagar they were hosted by Kenneth Hadow,[note 4] a British expatriate owner of a large estate. He had organized customs clearance for their baggage and also advised on suitable staff for local appointment. He arranged for the team to stay at a skiing hut at 10,000 feet (3,000 m) from where they made ski ascents to five nearby summits to acclimatize. On April 27 they returned to Srinagar and met up with the non-climbing team members; the Sherpas had travelled from Darjeeling.[26]

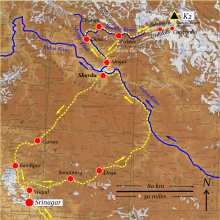

Approach to K2

At that time the road ended at Wayil just north of Srinagar, 330 miles (530 km) (or a month's trek) from the mountain, so after driving there on May 2 they took to foot and pony.[27] They travelled in stages of about 15 miles (24 km) a day, taking on fresh porters and ponies every three or four stages. Trekking via Sonamarg and the Zoji La pass into Baltistan they reached Skardu and crossed the Indus River into the Karokoram in an ancient hand-rowed barge. Cromwell wrote "This is indeed a bleak and barren country, and how the inhabitants manage to live fills me with a constant admiration and wonder. The hills are entirely barren of vegetation, which only exists on the irrigated alluvial fans." To cross the fast-flowing Shigar River required a ferry that was unable to carry their ponies. Following the river up past Shigar they went northwest and, at Dasu, east beside the Braldu River – the villages became progressively more poverty-stricken and diseased until they eventually reached Askole, the last habitation, which was comparatively wealthy. On May 22 they departed with 123 porters each bearing 60–65 pounds (27–29 kg) and passed the snout of the Biafo Glacier.[28]

On May 26 they reached the source of the Braldu River at the Baltoro Glacier at 11,500 feet (3,500 m). Passing Mustagh Tower to the north and then Masherbrum to the south they were held up by a porters' strike when they camped at Urdukas. On May 30 Cranmer got cold, wet and exhausted trying to retrieve a tarpaulin from a crevasse and some porters had to be led back to Askole because of snow blindness, caused by the lack of goggles. Next day they reached Concordia (15,092 feet (4,600 m)) where the Godwin-Austen Glacier enters the Baltoro – after turning into the Godwin-Austen they were at last able to see K2. The party had been in very good spirits throughout the journey. Base Camp was established at 16,500 feet (5,000 m) from where most of the porters were sent back down to Askole with instructions to return on July 23 – there would be fifty-three days to climb the mountain. Next day, after Wiessner, Cromwell and Pasang Kikuli had set off on a reconnaissance, Cranmer became very ill, probably with pulmonary edema, and Durrance, despite his lack of medical training, treated him very successfully, giving artificial respiration for two hours and possibly saving his life. However, this was the end of Cranmer's effective participation – he might have been Wiessner's best climber.[29]

Line of ascent

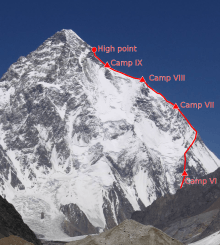

The camps were in the same locations as in 1938 and it was helpful that four of the Sherpas had been on the previous expedition.[30]

| Locations of camps on mountain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude feet[note 5] | Altitude metres | Status | Location |

| Base | 16,500 | 5030 | major | Godwin-Austen Glacier |

| I | 18,600 | 5670 | Abruzzi Ridge as 1909 camp | |

| II | 19,300 | 5882 | major | sheltered spot on Ridge |

| IIA | 20,000 | 6096 | dumping area near II | |

| III | 20,700 | 6310 | cache (site vulnerable to falling rocks) | |

| IV | 21,500 | 6553 | major | Red Rocks, below House Chimney |

| V | 22,000 | 6705 | right above House Chimney, start of sharp part of Ridge | |

| VI | 23,400 | 7130 | major | base of Black Tower (or pyramid) |

| VII | 24,700 | 7529 | major | plateau above Ridge and ice traverse |

| VIII | 25,300 | 7711 | assault | hollow on plateau |

| IX | 26,050 | 7940 | assault | south of summit cliffs, below the couloir later called the "Bottleneck" |

| high point | 27,450 | 8370 | no camp | turned back at start of summit snow plateau |

| Summit | 28,251 | 8611 | – | summit not reached |

Wiessner saw himself as the person to lead the climb up the mountain, as well as being the overall organizational leader. The appointment of Cromwell, who had not intended to climb higher than Camp IV, as deputy and the lack of other experienced climbers gave Wiessner an over-dominant position in the team.[32][33] This had caused no difficulties up to Base Camp but on the mountain Wiessner was to become progressively farther and farther separated from the main group of the team and no one seemed able to take charge of the logistics lower down. Of the better climbers, Cranmer was seriously ill and Durrance was greatly impeded because of still waiting for his proper boots. The Abruzzi Ridge can be climbed from Base Camp up to Camp VI in a few hours of good weather but in poor weather or with indifferent climbers the ridge is a dangerous place to be. Between Camp IV and Camp VII the Abruzzi Ridge is sharp, steep and unrelenting with exposure and rockfall being problems on the lower section. Strong winds can be a major difficulty – K2 partly protects the major eight-thousanders to the south but it itself is very exposed to storms.[32]

Progress up mountain

To Camp IV

On June 5 they carried 700 pounds (320 kg) up the Godwin-Austen glacier and its icefall to reach Camp I. After several carries Camp I was occupied on June 8 and next day Wiessner, Durrance and Pasang Kikuli reached Camp II which was to become the main low-level location for food and equipment to be stocked with 3,360 pounds (1,520 kg) of supplies.[34]

Wolfe's clumsiness as a climbing member of the team put others at risk but he was good company and very hard working so he was well liked. As time went by he associated himself more closely with Wiessner who seemed to be taking him as a favorite, possibly because he was substantially funding the expedition's costs.[35]

Leaving Cromwell to lead as far as Camp IV, on June 14 Wiessner returned to Base Camp where he found Cranmer in better health, able to organize things at base although he was not fit to climb higher. On June 17, back at Camp II, Wiessner found the advance party had not even reached the site of the 1938 Camp III – Cromwell, a fair weather climber with no leadership experience, was turning out to be a very timid leader, often making excuses for why activity should be postponed. Wiessner again took the climbing lead but even he took two days to reach Camp IV with a large team of eleven – as it turned out he continued to lead the climbing for the rest of the attempt on the summit.[36]

Storm

On June 21 there was a severe storm that lasted for eight days. At Camp IV the temperature dropped to −2 °F (−19 °C) and down at Camp II there were hurricane-force gusts of 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). On June 28 Tsering Norbu went down to Base Camp and was able to bring back up the mail that had arrived and, at last, Durrance's boots. The storm ceased suddenly on June 29 leaving Wiessner and Wolfe still confident of reaching the summit but the rest of the team had lost all enthusiasm for the expedition.[37]

On July 1 Durrance sent a Sherpa up to Camp VI with a note saying his boots had arrived and giving other news including that they had made no progress during the storm. Receiving the note at Camp V, Wiessner may have misunderstood the contents[note 6] because he replied starting "I am very disappointed in you ..." – in fact during the storm Durrance had been out carrying supplies more frequently than his leader. There was now a strong rift between Wiessner and the rest of the climbers, apart from Wolfe. After carrying supplies up to Camp III in another storm Cromwell was hurt in a fall and Sheldon got seriously frostbitten toes. He was sent down to Base Camp by Cromwell and stayed there for the rest of the expedition.[38]

Wiessner to Camp VII and return to Camp II

On June 30 Wiessner scaled the House Chimney, set up fixed ropes, and pulled up Pasang Kikuli. Next day, with a very tight rope, he managed to get Wolfe and another Sherpa up the cliffs and the four of them established Camp V. After a three-day storm Wiessner and the Sherpas climbed to the location for Camp VI and next day, July 6, climbed the Black Tower[note 7] to reach the top of the Abruzzi Ridge: Camp VII at 24,700 feet (7,529 m). During this time Wolfe had stayed at Camp V. No further supplies had been carried up even as far as Camp IV so Wiessner immediately went right down to Camp II to see what was going on.[39]

Wiessner and Wolfe to Camp VIII

Durrance and the others were astonished by the progress high on the mountain. They had been worrying that the advance team might be in trouble and had only made two trips to dump supplies at Camp III. Cheered by the developments, Durrance, Cromwell, Trench and six Sherpas resumed the ascent but found the work very hard in reaching Camp IV. At Camp V Durrance found frostbite in Wolfe's feet but, following in Wiessner's trail, they struggled up to Camp VI with Wolfe having very great difficulty. Overruling Durrance's medical advice, Wiessner allowed Wolfe to continue on up.[note 8] On July 13, ascending to Camp VII, Durrance became exhausted and went down to VI with four Sherpas while Wiessner, Wolfe and three Sherpas occupied the higher camp. Next day the higher party reached Camp VIII from where Tse Tendrup and Pasang Kitar were sent back to move supplies between VI and VII, supposedly to be arriving from lower on the mountain. The other Sherpas were to carry up to VIII to join Pasang Lama who had stayed there. Discounting the eight-day delay caused by the major storm, they had established Camp VIII in the same time it had taken the 1938 expedition. Their supply lines were, however, seriously overstretched.[41]

Durrance had been utterly exhausted descending to Camp VI – it can now be diagnosed he was suffering from hypoxia together with pulmonary or cerebral edema and he had scarcely managed to get there. He gave instructions to Tsering Norbu and Phinsoo to restock the camps up to VII or even VIII and then, with Pasang Kikuli who had serious frostbite and Dawa Thondup, he eventually got down to Camp II where he found everything in a terrible mess with Cromwell and Trench in a state of complete apathy. Now there was no link between the summit party and those at Camp II or below where no one felt in a condition to move. There was later to be great argument as to whether the team abandoned Wiessner or whether he had abandoned his team.[42]

Activities during summit attempts

A serious organizational difficulty had now arisen. Wiessner, Wolfe and Pasang Lama were up at 25,300 feet (7,700 m) at Camp VIII, ready to attempt the summit at 28,251 feet (8,611 m) and believing that supplies were being ferried up to the high camps to support them.[note 9] Down at Base Camp and Camp II they did not consider they had much to do. At Camps VI and VII were four Sherpas, led by the strong but inexperienced Tse Tendrup, but with no climbers, sirdar or deputy sirdar. Their rushed instructions had simply been to carry supplies further up and it is not clear they had understood,[note 10] let alone grasped the overall logistical situation.[43]

Summit attempts of Wiessner and Pasang Lama, July 17–21

From Camp VIII the final assault on the mountain was being contemplated with little understanding that the supply lines were vestigial. They started climbing on July 17 with Wiessner confident of success.[44]

By this time Wiessner had spent 24 days above 22,000 feet (6,700 m) and Wolfe 26 days.[note 11] They and Pasang Lama climbed strongly but on reaching the bergschrund it was clear that Wolfe could get no further so he returned to VIII. Above the bergschrund the snow was easier. Because they pitched their tent lower than they had hoped, next day they moved Camp IX up to the top of a rock pillar.[46] Later Wiessner was to write of his thoughts at this point

"Our position on the mountain was extremely favorable. We had built up a series of fully stocked camps up the mountain; tents with sleeping bags and provisions for many weeks stood ready at Camps II, IV, VI and VII. Wolfe stood at Camp VIII with further supplies (if indeed, he was not already on the way up to us), and here at Camp IX we had provisions for 6 days and gasoline for a longer period than that."

The weather was perfect and the summit was only 2,200 feet (670 m) above them as they launched their summit attempt at the late hour of 09:00 on July 19. They then reached a point of decision: to traverse right to reach a couloir, later known as the "Bottleneck", beside unstable ice from the summit cornice or, alternatively, a technical rock climb to the left free from objective dangers but very difficult for Pasang Lama.[note 13] Wiessner decided on the rock climb which took nine hours and was of unprecedented difficulty at such an altitude.[note 14] In fine weather they were now at about 27,450 feet (8,370 m) with only an easy 800-foot (240 m) crossing of the summit snow plateau to the top. Wiessner wanted to travel on through the night but Pasang Lama refused and would not pay out the rope. Wiessner agreed to turn back – he did not attempt the summit by himself – and, despite all the bad feeling that was later to ensue, he never criticized his Sherpa climbing partner. In gathering darkness they went back down the cliffs but while doing so Pasang Lama lost both pairs of crampons he was carrying. Wiessner wrote

"We continued down and reached our camp at 2:30 am.

I regretted many times on the way down that I had given in. It would have been so much easier for us to go on to the summit and return over the difficult part on the route the next morning.

We were quite tired when we arrived in camp."

— Wiessner

Disappointed that no supplies had arrived at Camp IX they rested next day in very warm weather and on July 21 set off again for the summit, this time choosing the couloir route.[note 15] This time the snow was in a bad condition and, unable to make adequate progress without their crampons, they returned to Camp IX.[46]

Sherpas at Camps VI and VII

For whatever reason, the four Sherpas, left to their own devices and with poor instructions, made no attempt to ferry supplies further up K2. Indeed, Tse Tendrup and Pasang Kitar decided to descend to the more comfortable Camp IV. On July 18 Pasang Kikuli and Dawa Thondup arrived from below[note 16] and they instructed Tse Tendrup and Pasang Kitar to go back up to Camps VI, VII or even VIII, ferrying goods upwards, and then to wait for news from above. They never got higher than Camp VI except on July 20 when they reached VII with Tse Tendrup venturing further to about 500 feet (150 m) below Camp VIII. Not daring to go on alone he shouted, three times, but got no reply.[note 17] Seeing signs of recent avalanches he rashly assumed the advance party had all been killed.[53]

Back at Camp VII Tse Tendrup persuaded the other Sherpas that everyone aloft had died, and, with only three days before the return home, they decided to descend. Moreover, because they had seen that the lower camps were being stripped they thought it would be helpful to clear Camps VII and VI as they went. By July 23 they were back at Base Camp.[54]

At Base Camp and Camp II

On July 18 Cromwell had sent a note up to Durrance asking him to organize retrieving and bringing back down the tents and sleeping bags from Camp IV and below. There was adequate food higher than this and porters were due back from Askole on July 23 for the return journey. Durrance sent the Sherpas up to clear the camps and he himself moved equipment from Camp II down to base. When Pasang Kikuli told Durrance the news from high on the mountain Durrance wrote in his diary "Found out Camp VIII established July 14, Hurrah!".[note 18][56]

Also on July 18 Sheldon and Cranmer took their own decision to leave on the return journey giving themselves time to study the geology near Urdukas before reaching home for the start of term at Dartmouth. This left only Cromwell, Durrance and Trench with Sherpas Pasang Kikuli, Sonam and Dawa Thondup. They saw Camp VI had been struck on July 21 and supposed the leading party would be back by July 23, the day the porters were due. However it was the four intermediate Sherpas who arrived down that day – nothing had been seen or heard of Wiessner and party since July 14.[57]

Wiessner's and Pasang Lama's descent, July 22–24

On July 22 Wiessner and Pasang Lama went down to Camp VIII to collect extra supplies and for Pasang Lama to be replaced by a fresher Sherpa, but, expecting to be going up again immediately, Wiessner left his sleeping bag behind although Pasang Lama took his one. What they found horrified them. Wolfe had been alone all the time, no supplies had arrived, and he had run out of matches, so he could neither cook food nor even melt ice. Wiessner could not understand where the reinforcements were, nor did he realize that, after nine days, people lower down might think he had met disaster.[46][note 19]

All three men went on down to Camp VII, which had been well-stocked last time they had last been there, but on the way Wolfe moved so clumsily that they had a serious fall when roped, almost sending all three down to the Godwin-Austen Glacier; this resulted in injuries around the waist for Pasang Lama and the loss of Wolfe's sleeping bag. Reaching the camp at dusk, they were met with another shock – not only were there no new supplies, but the tents had collapsed under snow; there were no mattresses, only one sleeping bag, and the food was scattered around.[note 20] Fortunately, they had been left stoves and fuel.[60]

Wiessner decided that Wolfe should stay at Camp VII while he and Pasang Lama descended, looking for supplies at Camp VI, still intending to make another attempt on the summit.[49][52][61] He later said that he agreed to leave Wolfe in camp, at Wolfe's own request, because the weather was good and Wolfe had managed alone before. However, it is possible that, after such a long time at high altitude, either of the two or both men were not thinking clearly. Wiessner and Pasang Lama descended, camp by camp, finding little food and no sleeping bags, until finally reaching Base Camp on July 24. Both were utterly exhausted, hardly able to walk, and Pasang Lama was in a very bad way. Wiessner was furious that they had been abandoned on the mountain, accusing first Cromwell, then Tendrup, of attempting to murder them, and threatening legal action. The well-to-do Cromwell, accustomed to polite deference, was appalled, and in turn accused Wiessner of abandoning Wolfe – Cromwell and Wiessner thus became enemies for life. Durrance kept quiet about his own role in clearing the lower camps, deliberately omitting telling Wiesnner that it had been under Cromwell's orders.[62]

Search for Wolfe

First rescue attempt

With Base Camp packed up and Cromwell and Trench starting off leading the porters back to Askole, Durrance set about trying to rescue Wolfe from Camp VII. On July 25 Durrance wrote "I left with Dawa Thondup, Phinsoo and Pasang Kitar to rescue Dudley". However, for the same day Wiessner's diary said "Jack, Phinsoo, Pasang Kitar, Dawa leave for Camp VII to meet Dudley. Jack, who feels well, may go on another summit attempt with me. I plan to follow tomorrow or in two days with Pasang Lama if he has recovered and if the beautiful weather holds...". This was an absurd idea and Durrance's sole aim was to try and rescue Wolfe, the only person still on the mountain. Durrance's party set off with orders that Durrance should only go to Camp II and the Sherpas were to climb alone after that. In fact they all reached Camp IV in two days but only two Sherpas had strength to continue so they went on up to Camp VI while Durrance and Dawa Thondup returned to base on July 27.[63]

Second rescue attempt

On July 28 (it is not clear whether as volunteers or under orders but more likely as volunteers) Pasang Kikuli and Tsering Norbu left Base Camp at 06:00 and were at Camp IV by noon continuing to Camp VI by the end of the day.[note 21] By climbing 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in one day they made the sort of alpine-style Himalayan ascent only achieved decades later by western climbers.[64]

With Tsering Norbu staying at Camp VI, Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar and Phinsoo reached Wolfe at noon, July 29.[note 22] At Camp VII things were in a terrible condition – no water or warm food; Wolfe was utterly apathetic and, because he was trapped in his tent, covered in urine and feces. He was uninterested in the letters they brought and refused to go down, telling them to return tomorrow when he would be ready. Back at Camp VI the Sherpas were stormbound so it was only on July 31 that the same three Sherpas again attempted the rescue. Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, Phinsoo and Wolfe were never seen alive again.[65][66][67]

Third rescue attempt

Tsering Norbu waited two days before descending from Camp VI. Starting at 07:30 he ran down the mountain reaching Base Camp early in the afternoon. Durrance wrote "The Sherpas are certain something awful has happened." Wiessner thought differently: "No, it seems impossible that anything should have happened to such an able group." There was no longer anyone with any degree of fitness but Wiessner set off on August 3 with Tsering Norbu and Dawa Thondup taking all day to reach Camp I where Wiessner changed his target for the next day from Camp IV to Camp II. A storm blew in and lasted until August 7 when Tsering Norbu claimed that what he had said previously was wrong – they had found Wolfe with no food at all at Camp VII. Even Wiessner now lost all hope: Wolfe and three Sherpa rescuers were all dead.[note 23] The rescue team managed to get back to base but all of them were in a pitiful state.

Return to Srinagar

Sheldon and Cranmer were first back home and had little to report since they had left well before the tragedy started.[71]

Wiessner and Durrance retraced their outward route until at Askole they crossed the Braldu River and went over the 16,630-foot (5,070 m) Skoro La to reach Shigar where they started drafting their report on the expedition. They seemed in accord on the contents and there is no evidence they had any arguments. They rafted down the Shigar River to Skardu where they again departed from their previous route by trekking to Gurais from where they telegraphed a number of reports, including to The Times of India. On August 27 at Bandipora they met Cromwell and, according to Durrance's personal diary which provides the only evidence, when he saw the draft report he was enraged. He shouted that Wiessner had murdered Wolfe and the Sherpas. Not only this but Cromwell and Trench had already been at Srinagar where they had been making their views known to the British community. Cromwell had also cabled the AAC to give them their first news of the failure of the expedition.[72]

On August 28 when they reached Srinagar the final draft of the expedition report was ready. This, and letters that had been sent by Cromwell and Trench to the AAC, were to cause major arguments, possibly exacerbated by the imminence of war in Europe.[73]

Repercussions in Srinagar

Durrance, knowing about the incendiary nature of Cromwell's and Trench's letters and after speaking with Hadow, decided he would not raise any complaints about Wiessner's leadership and he kept quiet until after Wiessner's death. D.M. Fraser, the British Resident for Kashmir, succeeded in blocking Cromwell's and Trench's letters but he read out both of them to Edward Millar Groth, the US Consulate General for Calcutta, who happened to be at Srinagar. Both letters then went missing with no record being kept. At Fraser's request Groth held a meeting with Wiessner and Durrance (it lasted seven hours) and then at the US Secretary of State's request wrote an official report for Washington. Groth dismissed Trench's letter as superficial and not worthy of credence whereas Cromwell's accusations he considered vindictive and exaggerated although they also contained some slight elements of truth.[74]

Wiessner's report

Wiessner's report to the AAC[note 24] blandly described the sequence of major events during the expedition with particular praise for Pasang Kikuli and Tsering Norbu. He justified Wolfe being left at Camp VII because Wiessner and Pasang Lama had intended returning up from Camp VI with additional supplies and equipment. However, each lower camp had been inexplicably cleared so they were unable to go back up. He did not lay any blame for the expedition's shortcomings, simply saying the conditions were adverse and people had become ill and exhausted.[76]

Groth's report

Groth's September 13 report to the US Secretary of State[note 25] enclosed Wiessner's report to the AAC but Groth's report itself was not made public nor was it communicated to the AAC.[note 26] He acknowledged that Durrance had provided additional information over that supplied by Wiessner. He accepted Wiessner's report but said he thought there had been personality clashes that might be due to someone with a German temperament leading American climbers. He thought Wiessner was a good climber and leader but had been too forceful and abrupt. He felt the Americans had made insufficient effort to understand him and that some, particularly those paying their own expenses, had wrongly felt entitled to have an equal say in the running of the expedition.[79]

Groth considered the accident was due to a combination of circumstances for which Wiessner could not be held solely responsible but that Wiessner should have taken far greater care in selecting the expedition's members bearing in mind climbing ability and temperament. He thought it might be that Wolfe, because of his financial contribution, had induced Wiessner into allowing him to climb too high. Tse Tendrup's false report of the deaths of the three leading climbers should not have been believed so readily. He praised the Sherpas who volunteered to try to rescue Wolfe and did not blame Wiessner for allowing their attempt. He criticized Cromwell and Trench for returning early to Srinagar and considered Trench had been entirely unsatisfactory on the expedition.[79]

Return to America

Delayed by the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939, Wiessner flew to Cairo on September 20 from where he returned by ship. Durrance, happy the expedition was over, stayed in India for several more weeks and only reached home at the end of the year. Back in America Cromwell again accused Wiessner of murdering Wolfe. Also, Wiessner gave an unfortunate interview to the New York Times saying, in his German accent, that on high mountains, as in war, one must expect casualties. A very public controversy started with people, including mountaineers, taking both sides but with a lot of criticism of Wiessner for abandoning Wolfe. These had been the first deaths on an American overseas mountaineering expedition and there were many recriminations. Fearing a split in its membership the American Alpine Club set up a committee to inquire into the matter and the bland report that resulted merely stated that it was the members of the expedition who could best account for what had happened. Wiessner and Cromwell both resigned from the AAC.[80]

Later controversy

Although criticism of Wiessner lingered, matters calmed down until in 1956 Wiessner published a book (in German) about the expedition and an article in the American mountaineering magazine Appalachia.[47][81][82] He raised the matter of the camps having been cleared while the lead climbers were still high on the mountain – something that had previously been glossed over. Wiessner wrote that on June 23, 1939 he had picked up a crumpled note from the floor of Camp II after his descent from Camp VII. This note had never been mentioned before. It was written by Durrance (Wiessner recognized the handwriting) and it gave congratulations for reaching the summit and it said that Durrance on the previous day had ordered all the sleeping bags to be taken down from Camp IV and that next day (June 19, 1939) all the tents and sleeping bags, including those at Camp II, were being removed to Base Camp.[note 27] Durrance did not attempt to refute this story and so vehement criticism was directed against him for betraying Wiessner.[84] Wiessner gained rehabilitation, being elected as an honorary member of the AAC in 1966, and by the 1980s the American mountaineering community had developed a great admiration for him.[85]

In the 1980s Andrew Kauffman and William Putnam[note 28] started researching to write Wiessner's biography.[89][90] In 1984 Wiessner had told Putnam he had passed the crumpled note to a member of the AAC committee of inquiry without keeping any copy.[91] The note was never reported on and has since vanished without trace, despite careful searches.[92] Interviewed by Kauffman in 1986–1987, Durrance broke his silence to say that he had no memory of leaving such a note. Wiessner died in 1988 and only then in 1989 Durrance for the first time made his personal, handwritten diary available. It records that Cromwell decided to clear the camps and wrote a note to the Sherpas at Camp VII asking them to do this.[93] Changing their book from a biography to one about the expedition, in 1992 the authors wrote that they found Durrance's diary reliable and they believe the most likely explanation is that, if there was a note, it was written by Cromwell for sending up to the Sherpas at Camp VII. Durrance had been keeping quiet for fifty years to protect Wiessner and Cromwell who had also recently died.[94][95] They also regarded it as a serious error that Wolfe was left up at Camp VII while the others descended.[61][note 29] Cromwell's decision to clear Camps IV and below was not as unreasonable as it seemed because he had no reason to think Camps VII and VI would be cleared – the Sherpas cleared the higher ones either through misunderstanding their orders or because, believing the lead climbers were dead and seeing the lower camps were being stripped, they assumed the higher camps were no longer needed.[99]

In 1961 Fosco Maraini described it as "one of the worst tragedies in the climbing history of the Himalaya".[100] On the other hand, in his 2013 book Jim Curran remarks that the expedition was so nearly an outstanding success. On his summit push, if Wiessner had chosen the easier route up "Bottleneck Couloir", they might have reached the top and been able to return to Camp IX all in the one day. With Sherpas and equipment still in place at the high camps they would probably all have been able to return safely. They would have been the first people to climb an eight-thousand-metre mountain and would have succeeded without bottled oxygen. There would have been no recriminations.[101]

Notes

- Note that Vittorio Sella was not on the 1939 expedition and his photographs shown in this article were taken on an earlier expedition.

- An annotated image is viewable at commons:File:K2 sella 1909.jpg.

- The upgrade to first class was at Wolfe's own expense.[23]

- Kenneth Hadow was the grandnephew of Douglas Hadow, killed on the First ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865.[13] Wiessner had first met him on the 1932 Nanga Parbat expedition.[25]

- Altitudes are as given in Wiessner's report.[31]

- Wiessner certainly thought that Durrance had received his boots on June 21 when in fact they arrived with him on June 28.

- Also called the Black Pyramid.

- Much later he claimed Durrance's advice had been given because he was jealous of Wolfe's good progress.[40]

- They hoped that Durrance and Pasang Kikuli, the sirdar, would be around Camp VI but this hope turned out to be misplaced.

- These Sherpas and the American climbers had no language in common.

- Although it was not clearly understood in 1939, above about 22,000 feet (6,700 m) the human body and mind progressively deteriorates.[45]

- Wiessner as quoted in Isserman & Weaver who go on to comment that the position was, in fact, extremely unfavorable.[48] See also Cranmer & Wiessner.[49]

- The couloir has been the site of several later tragedies, see for example 2008 K2 disaster.

- As of 2009 this rock climb has never been repeated – the "Bottleneck" route has always been used.[50]

- Wiessner had previously seen from above that the couloir was easier than he had originally anticipated.[51]

- They had arrived at VI with Durrance's instructions to bring down tents and equipment.

- This was the day that Wiessner and Pasang Lama were resting at Camp IX and, it seems, Wolfe was asleep at Camp VIII.[52]

- His remarks were not those of someone jealous of the assault team.[55]

- It was later supposed that the Sherpas had misunderstood the instructions to ferry supplies up to Camp VIII.[58]

- Wiessner's book says there were no mattresses but his diary says they had one each.[59]

- Climbing at only slightly under 1,000 feet (300 m) per hour, an exceptional rate.

- Wolfe had spent 38 days continuously above 22,000 feet (6,700 m) and 16 days averaging 25,000 feet (7,600 m) without supplementary oxygen. At that time no one else had achieved this even with oxygen.

- In 1995 some remains were found on the Godwin–Austen Glacier of what were probably the Sherpas and in 2002, elsewhere on the glacier, Wolfe's remains were found along with parts of his tent.[67][68][69][70]

- Kauffman & Putnam supply the full text.[75]

- Kauffman & Putnam supply the full text.[77]

- In writing his report Groth received advice from Roger Wilson, a British alpinist and president of the Himalayan Club who had seen Wiessner's report and Groth's notes on his meetings with Wiessner and Durrance, but not the letters of Cromwell or Trench.[78]

- This account is incompatible with Wiessner accusing Cromwell (deputy leader and senior to Durrance) of murder. Also, if left by Durrance at Camp II, the note had no sensible rationale because by the time it was found it would have been apparent the camps had been cleared.[83]

- Kauffman is a former vice president of the AAC and Putnam is a former president of the AAC (1974–1976).[86][87][88]

- Likewise Kenneth Mason, a founding member of the Himalayan Club and first editor of the Himalayan Journal, wrote in 1955 "It is difficult to record in temperate language the folly of this enterprise".[96][97] But Viesturs and Roberts claim Mason gives "an utterly garbled summary of the events".[98] See also Charlie Houston's conclusions in his review of Kauffman's and Putnam's book.[90]

References

Citations

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 18–22.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 23–24.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 25–27.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 26–27.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 23–33.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 80.

- Conefrey (2001).

- Vogel & Aaronson (2000).

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 36.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 215.

- Jordan (2010), p. 82.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 36–44.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 216.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 40–41.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 36–44,59.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 111.

- Jordan (2010), pp. 86–87.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 54.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 86,114.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 46–47.

- Jordan (2010), p. 85.

- Jordan (2010), p. 115.

- Jordan (2010), p. 97.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 45–50.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 52.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 51–56.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 19,57.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 57–66.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 58,66–74,80.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 77.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 15.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 75–79.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 217.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 80–83.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 84.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 84–87.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 84–91.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 91–95.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 96–97.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 100–102.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 97–103.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 104–105.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 103,107,111,116.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 103–106,111.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 173–180.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 116–119.

- Wiessner & Grassler (1956).

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 218–219.

- Cranmer & Wiessner (1940).

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 130.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 131.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 219.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 112.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 112–113.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 106–107.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 106–110.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 112–114.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 103–111.

- Sale (2011), p. 88.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 119–121.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 122–123.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 122–124.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 125–128.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 128–129.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 129–132.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 220–221.

- Tremlett, Giles (July 19, 2002). "Melting snows shed new light on K2's great mystery". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 132–133.

- Griffin, Lindsay (2003). "K2, discovery of Dudley Wolfe's body". American Alpine Journal. 77 (45): 359–360. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Jordan (2010), p. 16–18,220.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 134.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 134–137.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 136–137.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 136–141.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), "Appendix F. Report of the American Alpine Club Second Karakoram Expedition", pp 195–201.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 195–201.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), "Appendix E. The Groth Report", pp 187–194.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), "Appendix G. The Wilson Analysis", pp 202–203.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 187–194.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 141–143,150.

- Wiessner (1956), pp. 60–77.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 151.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 205.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 12,144–153.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 143,153.

- "Past Presidents". The American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Putnam, William L. (2003). "Andrew John Kauffman II, 1920–2002 – AAC Publications – Search The American Alpine Journal and Accidents". publications.americanalpineclub.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), publisher's blurb on dust jacket.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 12.

- Houston, Charles S. (1993). "Book Reviews: K-2, The 1939 Tragedy". American Alpine Journal. 35 (67): 298–300. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 186.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 204–205.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 13,153,185.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 144–153.

- Putnam, William L. (2011). "A Great Many Years". The American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 221.

- "About the Journal". Himalayan Club. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Viesturs & Roberts (2009), p. 150.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 103,111–113,159.

- Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 11.

- Curran (2013), p. 105.

Works cited

- Conefrey, Mick (2001). Mountain Men: The Ghosts of K2 (television production). BBC/TLC. Event occurs at 04:13 & 06:10. The video is hosted on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/54661540

- Cranmer, Chappell; Wiessner, Fritz (1940). "The Second American Expedition to K2". American Alpine Journal: 9–19.

- Curran, Jim (April 11, 2013). "Chapter 7. Neither Saint nor Sinner". K2: The Story Of The Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 88–105. ISBN 978-1-4447-7835-9.

- Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). "Chapter 5. Himalayan Hey-Day". Fallen Giants : A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11501-7.

- Jordan, Jennifer (2010). The last man on the mountain : the death of an American adventurer on K2. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07778-0.

- Kauffman, Andrew J.; Putnam, William L. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-323-9.

- Sale, Richard (2011). "Chapter 3. The Americans Head for K2". The Challenge of K2 a History of the Savage Mountain (ebook). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Discovery. ISBN 978-1-84468-702-2.

- Viesturs, Ed; Roberts, David (2009). "Chapter 4. The Great Mystery". K2: Life and Death on the World's Most Dangerous Mountain (ebook). New York: Broadway. ISBN 978-0-7679-3261-5.

- Vogel, Gregory M.; Aaronson, Reuben (2000). Quest For K2 Savage Mountain (television production). James McQuillan (producer). National Geographic Creative. Event occurs at 11:55. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1939 K2 expedition. |

- American Alpine Club Library blog (February 17, 2018). "K2 1939: The Second American Karakoram Expedition". American Alpine Club. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- Conefrey, Mick (2015). The Ghosts of K2: the Epic Saga of the First Ascent. London: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-78074-595-4.

- Falvey, Pat; Sherpa, Pemba Gyalje (2013). The Summit: How Triumph Turned to Tragedy on K2's Deadliest Days. Killarney, Ireland: Beyond Endurance Publishing/O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-1-84717-643-1.

- Horrell, Mark (October 21, 2015). "Book review: The Ghosts of K2 by Mick Conefrey". Footsteps on the Mountain. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- House, William P. (1939). "K2—1938". American Alpine Journal: 229–254. – report of first (1938) expedition to K2

- Houston, Charles S.; Bates, Robert H. (1954). K2, the Savage Mountain. McGraw Hill. (primarily about the 1953 K2 expedition but also discussing those of 1938 and 1939)

- Wiessner, Fritz H.; Grassler, Franz (1956). K2: Tragödien und Sieg am Zweithöchsten Berg der Erde (in German). Munich: Bergverlag Rudolf Rother.

- Wiessner, Fritz H. (June 1956). "The K2 Expedition of 1939". Appalachia. 31: 60–77.