1916 New York City polio epidemic

The 1916 New York City polio epidemic was an epidemic of polio ultimately infecting several thousand people, and killing over two thousand, in New York City, primarily in the borough of Brooklyn. The epidemic was officially announced in June 1916, and a special field force was assembled under the authority of Dr. Simon R. Blatteis of the New York City Health Department's Bureau of Preventable Diseases, with broad authority to quarantine those infected with polio and institute hygiene measures thought to slow the transmission of the disease. Polio was a poorly understood disease in this era, and official efforts to stem its spread consisted primarily of quarantines, the closure of public places, and the use of chemical disinfectants to cleanse areas where the disease had been present. Special polio clinics were established at various locations in the city for the treatment and quarantine of patients.

| 1916 New York City polio epidemic | |

|---|---|

| Disease | Polio |

| Location | New York City |

| Arrival date | June 1916 |

| Confirmed cases | Several thousands |

Deaths | over 2,000 |

In addition, many informal remedies or preventative measures were tried by the frightened population, while public activities largely fell silent. Ultimately, the epidemic subsided in the winter months, with the cause remaining a mystery to investigators and the public.

Progress of the epidemic

On Saturday, June 17, 1916, an official announcement of the existence of an epidemic polio infection was made in Brooklyn, New York. Over the course of that year, there were over 27,000 cases and more than 6,000 deaths due to polio in the United States, with over 2,000 deaths in New York City alone.[1]

According to the figures compiled by the New York City Department of Health, by June 1916 there were 114 verified cases of infantile paralysis in Brooklyn, practically all of them in the old South Brooklyn section. The outbreak appeared to be confined to infants and young children, less than 10% of the cases occurring in children over five years of age. The Department of Health stated that a careful investigation had failed to substantiate the view that the schools had a share in spreading the disease, pointing out that over 90% of the children were under the typical school age; that the cases were not limited or even more prevalent in any one school district, and that they were not at all limited to children in the same classroom.[2]

On June 26, 1916, the Department of Health issued a bulletin noting 37 additional cases of infantile paralysis reported to the Department of Health making a total to date of 183 cases in Brooklyn. A study of the situation indicated that the disease was spreading in a southerly direction and was invading the Parkville section, to the east of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. In the week preceding that report, 12 deaths were reported from anterior poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis) in the Greater City, eleven occurring in Brooklyn, almost as many as occurred in the entire city during the year 1915, when 13 deaths from this disease were reported for the entire year in the Greater City. The twelfth case was reported to the Department from Staten Island. It was located in an Italian-American district, like most of the Brooklyn cases.[2]

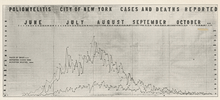

On June 28, 1916, another 23 cases were reported, bringing the total in Brooklyn to 206 cases.[2] On July 1, 1916, 53 new cases and 12 deaths were reported in New York City, making a total of 59 deaths since the outbreak of the epidemic.[2] Both illnesses and deaths thereafter continued to increase on a daily basis throughout the month of July, peaking in early August, by which time the total number of cases was in the tens of thousands, and the number of deaths was over one thousand. The disease then began a slow decline for much of the remainder of the year.

Responses

The 1916 epidemic caused widespread panic and thousands fled the city to nearby mountain resorts; movie theaters were closed, meetings were canceled, public gatherings were almost nonexistent, and children were warned not to drink from water fountains, and told to avoid amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches.[1] The names and addresses of individuals with confirmed polio cases were published daily in the press, their houses were identified with placards, and their families were quarantined.[3] Cities in neighboring counties and states enacted rules barring New Yorkers from entering those cities, with Hoboken, New Jersey going so far as to have police officers intercept travelers arriving from Brooklyn by ferry and escort them back to Brooklyn.[4] Hiram M. Hiller, Jr. was one of the physicians in several cities who realized what they were dealing with, but the nature of the disease remained largely a mystery.[1] In the absence of proven treatments, a number of odd and potentially dangerous polio treatments were suggested. In John Haven Emerson's A Monograph on the Epidemic of Poliomyelitis (Infantile Paralysis) in New York City in 1916[5] one suggested remedy reads:

Give oxygen through the lower extremities, by positive electricity. Frequent baths using almond meal, or oxidising the water. Applications of poultices of Roman chamomile, slippery elm, arnica, mustard, cantharis, amygdalae dulcis oil, and of special merit, spikenard oil and Xanthoxolinum. Internally use caffeine, Fl. Kola, dry muriate of quinine, elixir of cinchone, radium water, chloride of gold, liquor calcis and wine of pepsin.[6]

Because of the relation alleged to exist between polio and the stable fly, a survey was made to determine whether the cases were in the vicinity of stables, and the Sanitary Bureau took special pains to see that the manure in all of the stables in the affected districts was properly disposed of to prevent the breeding of flies.[2]

In response to a call issued by Commissioner Emerson, a conference of experts was held at the Health Department on June 28, 1916, to discuss plans for the control of infantile paralysis in Brooklyn. At the conference it was decided to organize a special field force in Brooklyn under Simon R. Blatteis of the Department's Bureau of Preventable Diseases. A special staff of medical inspectors, sanitary inspectors, nurses, and sanitary police, would assist Blatteis, visiting all cases daily and see that strict quarantine was maintained, and that all the premises where a case of infantile paralysis exists were placarded. The Department of Health prepared a special pavilion at its Kingston Avenue Hospital for sufferers from infantile paralysis to be cared for by skilled specialists. The Department organized a special visiting staff of experts, including specialists in children's diseases, orthopedists and neurologists, to assist the regular attending staff. The Health Department insisted that a patient, in order to be allowed to remain at home, should have a separate room, separate toilet, a special person in attendance for nursing purposes, and facilities for the proper disposal of all discharges. Where these facilities could not be provided, the Health Department would hospitalize the patient at no charge.[2] By July 8, 1916, Blatteis had established six clinics in Brooklyn specifically set up to receive polio victims.[7]

References

- Melnick J (1 July 1996). "Current status of poliovirus infections". Clin Microbiol Rev. 9 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.3.293. PMC 172894. PMID 8809461. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (1916), Vol. 175, p. 29-30.

- Risse GB (1988). Fee E, Fox DM (eds.). Epidemics and History: Ecological Perspectives. in AIDS: The Burden of History. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-06396-1.

- "Cities of Nearby States Barring Out New Yorkers", Brooklyn Times Union (July 14, 1916), p. 2.

- Emerson H (1977). A monograph on the epidemic of poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis). New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-09817-0.

- Gould T (1995). A summer plague: polio and its survivors. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-300-06292-3.

- "Fifty-six Epidemic Cases Reported in Borough", The Brooklyn Citizen (July 8, 1916), p. 3.