1909 Giro d'Italia

The 1909 Giro d'Italia was the inaugural running of the Giro d'Italia, a cycling race organized and sponsored by the newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport. The event began in Milan on 13 May with a 397 km (247 mi) first stage to Bologna, finishing back in Milan on 30 May after a final stage of 206 km (128 mi) and a total distance covered of 2,447.9 km (1,521 mi). The race was won by the Italian rider Luigi Ganna of the Atala team, with fellow Italians Carlo Galetti and Giovanni Rossignoli coming in second and third respectively.

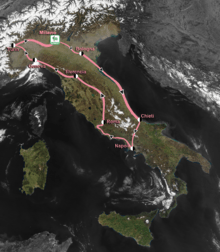

Overview of the stages: route clockwise from Milan, down to Naples, then up to Milan | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 13–30 May | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 2,447.9 km (1,521 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 89h 48' 14" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Conceived by La Gazzetta to boost its circulation at the expense of its rival Corriere della Sera, the 1909 Giro was the first stage road race. Its eight stages, although relatively few compared to modern Grand Tours, were each much longer than those raced today. The event began with a long primarily flat stage that was won by Dario Beni. He lost the lead after the next stage to the eventual winner Luigi Ganna, who in turn lost it to Carlo Galetti after the mountainous third stage. Ganna regained the lead after the fourth stage and successfully defended it all the way to the finish in Milan, winning three stages en route. Atala won the team classification.

Origin

The idea of holding a bicycle race around Italy was first suggested in a telegram sent by Tullo Margagni, editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport, to the paper's owner Emilio Costamagna and cycling editor Armando Cougnet.[1][2][3] La Gazzetta's rival, Corriere della Sera was planning to hold a bicycle race of its own, flushed with the success of its automobile race.[2][3][4] Morgagni decided to try and hold the race before Corriere della Sera could hold theirs, and following La Gazzetta's success in creating the Giro di Lombardia and Milan–San Remo, Costamagna decided to back the idea.[3][5] The inaugural Giro d'Italia bicycle race was announced on 7 August 1908 in the first page of that day's edition of La Gazzetta,[4] to be held in May 1909.[4] The idea of the race was influenced by the success of the French magazine L'Auto's organization of the Tour de France.[5]

Since the newspaper lacked the necessary 25,000 lire to sponsor the race,[2] the organizers consulted Primo Bongrani, a sympathetic accountant at the bank Cassa di Risparmio. He proceeded to solicit donations from all over Italy,[3] and succeeded in raising sufficient money to cover the operating costs.[3] The prize money came from a casino in San Remo after Francesco Sghirla, a former Gazzetta employee, encouraged them to contribute to the race.[2][3] Even Corriere, La Gazzetta's rival, donated 3,000 lire.[2]

Rules and course

Both teams and individual riders were allowed to enter the race,[3] which was run in eight stages with two to three rest days between each stage. Compared to modern races the stages were extraordinarily long, with an average distance of more than 300 km (190 mi), compared to the 165 km (103 mi) average stage length in the 2012 Giro d'Italia.[3]

The route was primarily flat, although it did contain a few major ascents.[3] The third stage contained ascents to Macerone, Rionero Sannitico, and Roccaraso.[3][6] The Giro's sixth stage contained only one pass, the Passo Bracco.[3] The seventh stage was the last to contain any major ascents: the climbs of the Colle di Nava and the ascent to San Bartolomeo.[3]

Riders were required to sign in at checkpoints during each stage to minimize the opportunities for cheating;[3] they were also photographed at the beginning and end of each stage, and the images compared by the judges.[3] Riders could receive assistance when repairing their bicycles,[3] but were not allowed to replace their machines if they became damaged during the course of the stage.[3]

The inaugural Giro used a points system to determine the race winner.[3] The organizers chose to have a points system over a system based around elapsed time after the scandal that engulfed the 1904 Tour de France.[3] Another factor in the organizer's decision was that it would be cheaper to count the placings of the riders rather than clocking their times during each stage.[3] The race leader was determined by adding up each rider's placing in each stage. Thus if a rider placed second in the first stage and third in the second stage he would have a total of five points, and whoever had the lowest points total was the leader. Under this system Luigi Ganna was declared the winner, but had the Giro been a time-based event he would have lost to the third-place finisher Giovanni Rossignoli by 37 minutes.[7][8]

The winner of the general classification received a grand prize of 5,325 lire.[4][8] Every rider who finished the race with more than 100 points without winning any prizes in any of the stages was given 100 lire.[9]

Participants

A total of 166 riders signed up to participate in the event.[3][10] Twenty of the riders who entered were non-Italians: fifteen were French, two were German, one was Argentinian, one was Belgian, and one was from Trieste, which at the time was not a part of Italy.[3] Only 127 riders started the first stage of the race,[4][8] all but five of Italian descent,[8] of whom only 49 reached the finish in Milan on 30 May.[4][8] Riders were allowed to enter the race as independents or as a member of a team.[3]

The two best-known Italians taking part in the race were Luigi Ganna and Giovanni Gerbi.[3] Gerbi was the more successful of the two, having won the Giro di Lombardia, the Milano–Torino, and several other one-day races.[3] Ganna had won Milan–San Remo earlier the same year – notably the first Italian winner of the race.[3] The peloton also featured two Tour de France winners, Louis Trousselier and Lucien Petit-Breton,[3][11][12] as well as two future Giro d'Italia winners: Carlo Galetti and Carlo Oriani.[13]

Race overview

The inaugural Giro d'Italia's first stage, 397 km (247 mi) from Milan to Bologna, began on 13 May 1909 at 2:53 am in front of a large crowd.[4][8] 127 riders set off from the starting line outside La Gazzetta's headquarters in the Piazzale Loreto.[4][8][14] The stage was marred by mechanical issues and crashes owing to bad weather,[10] the first mass crash occurring before dawn less than 2 km (1 mi) from the start.[3] Luigi Ganna, leading after the first real climb near Lake Garda,[3] was delayed by a puncture with about 70 km (43 mi) to go and the other racers attacked, but he caught them again after they were stopped by a train crossing.[3] The leading riders then made their way into Bologna, where Dario Beni won the stage.[10] The second stage, 378.5 km (235 mi) long, saw the first uphill finish, into Chieti,[3] where Giovanni Cuniolo edged out Ganna for the stage win.[10] Ganna's second place was nevertheless high enough to make him the new race leader.[3][10]

The third stage, to Naples, was 242.8 km (151 mi). Before the start, three riders were disqualified and subsequently removed from the race for taking a train during the second stage.[3][8] They were caught after failing to pass through an unexpected checkpoint set up by the organizers.[3] The start of the third stage was moved downhill after the opening descent was found to be too dangerous for the participants' brakes.[3] The stage featured three major climbs.[3] After the mountains Giovanni Rossignoli pursued the leader, Carlo Galetti,[3] eventually catching him and going on to win the stage, while Galetti took the race lead away from Ganna.[6] On the fourth stage, 228.1 km (142 mi) from Naples to the Italian capital Rome,[6] French rider Louis Trousselier was doing well until he ran over tacks strewn on the road by spectators, and the other riders left him behind.[3] Galetti and Ganna formed a group at the front[3] and Ganna went on to win the stage in front of thousands of spectators, retaking the race lead by a single point.[3][6]

The fifth stage was 346.5 km (215 mi) to Florence. Like the fourth, it was plagued by punctures.[6] Luigi Ganna led until he had a flat tyre with about 10 km (6 mi) to go.[3] A few riders passed him as he repaired it[3] but he chased them down and won the stage.[3][6] On the sixth stage, 294.4 km (183 mi) from Florence to Genoa,[9] Carlo Galetti and Giovanni Rossignoli broke away from the leading group of seven as they neared the downhill finish, with Rossignoli winning the stage in front of a large crowd.[3][9] Race leader Ganna had suffered more punctures but managed to fight his way back to finish third.[9]

The seventh stage, 357 km (222 mi), was scheduled to run from Genoa to Turin. Massive crowds at the start led Armando Cougnet to introduce a rule forbidding riders to attack over the first few kilometers until the peloton was outside the city and the race proper could begin.[3][9] There was also rumored to be close to 50,000 spectators and a bakers' strike in Turin, so Cougnet switched the finish to the city of Beinasco, about 6 km (4 mi) short of Turin.[3] Ganna and Rossignoli led for most of the stage until about 6 km (4 mi) before the finish, when Ganna attacked and Rossignoli could not counter.[3][9] Ganna's win extended his race lead over Carlo Galetti.[3][9]

The eighth and final stage started in Turin, covered 206 km (128 mi), and finished in Milan in front of a crowd of more than 30,000.[3][9] Ganna was amongst the leading group until he suffered a flat tyre.[3][9] He managed to fight his way back until, with the leaders in sight, he had another puncture.[3][9] The leading group pulled away until the race directors stopped them to let Ganna catch up.[3] Escorted by mounted police, the riders then made their way into Milan's Arena Civica stadium for the finish.[2] As the racers geared up for the sprint finish a police horse fell, causing a few riders to crash.[3] Dario Beni avoided the incident and edged out Galetti for the stage win, with Ganna coming in third.[3][9] Thus Ganna became the first winner of the Giro d'Italia.[9][15] He and his team, Atala, also won the team classification.[3][9]

Results

Stage results

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[Notes 1] | Winner | Race Leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 May | Milan to Bologna | 397 km (247 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 2 | 16 May | Bologna to Chieti | 375.8 km (233.5 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 3 | 18 May | Chieti to Naples | 242.8 km (150.9 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 4 | 20 May | Naples to Rome | 228.1 km (141.7 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 5 | 23 May | Rome to Florence | 346.5 km (215.3 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 6 | 25 May | Florence to Genoa | 294.1 km (182.7 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 7 | 27 May | Genoa to Turin | 354.9 km (220.5 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 8 | 30 May | Turin to Milan | 206 km (128 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| Total | 2,447.9 km (1,521 mi) | ||||||

General classification

Forty-nine cyclists completed all eight stages. The points each received from their stage placings were added up for the general classification, and the winner was the rider with the fewest accumulated points. Ernesto Azzini won the prize for best ranked isolati rider in the general classification.[18]

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atala | 25 | |

| 2 | Legnano | 27 | |

| 3 | Bianchi | 40 | |

| 4 | Legnano | 59 | |

| 5 | Stucchi | 72 | |

| 6 | — | 77 | |

| 7 | Bianchi | 91 | |

| 8 | Bianchi | 98 | |

| 9 | Bianchi | 117 | |

| 10 | Legnano | 139 |

| Final general classification (11–49)[3][9][19] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

| 11 | Atala | 141 | |

| 12 | Peugeot | 141 | |

| 13 | Bianchi | 157 | |

| 14 | Legnano | 157 | |

| 15 | Piomagno | 164 | |

| 16 | — | 166 | |

| 17 | — | 166 | |

| 18 | — | 177 | |

| 19 | Felsina | 185 | |

| 20 | — | 206 | |

| 21 | — | 208 | |

| 22 | — | 221 | |

| 23 | — | 221 | |

| 24 | — | 222 | |

| 25 | — | 224 | |

| 26 | — | 229 | |

| 27 | — | 245 | |

| 28 | — | 245 | |

| 29 | — | 246 | |

| 30 | — | 248 | |

| 31 | — | 255 | |

| 32 | — | 265 | |

| 33 | — | 265 | |

| 34 | — | 274 | |

| 35 | — | 275 | |

| 36 | — | 281 | |

| 37 | — | 282 | |

| 38 | — | 284 | |

| 39 | — | 284 | |

| 40 | — | 284 | |

| 41 | — | 284 | |

| 42 | — | 285 | |

| 43 | — | 286 | |

| 44 | — | 290 | |

| 45 | — | 291 | |

| 46 | — | 292 | |

| 47 | — | 292 | |

| 48 | — | 292 | |

| 49 | — | 297 | |

Aftermath

The first Giro d'Italia was a great success, prompting organizers to arrange a second one for 1910.[20] The race substantially increased La Gazzetta's circulation,[3] and the starts and finishes were attended by large audiences.[9][4] Ganna's prize money helped him start his own bike factory in 1912.[3] The newspaper ran the event through 1988, when the RCS Organizzazzioni Sportivi company was created to run it.[21]

References

Footnotes

- In 1909, there was no distinction in the rules between plain stages and mountain stages; the icons shown here indicate that the third, sixth, and seventh stages included mountains.

Citations

- McHugh, Michael (21 February 2013). "Cycling: Giro d'Italia to begin in Ireland in 2014". The Independent. Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Fotheringham (2003), pp. 103–104.

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol. "1909 Giro d'Italia". Bike Race Info. Dog Ear Publishing. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "History". La Gazzetta dello Sport. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Reissner, Leslie (23 June 2011). "The Giro d'Italia: Don't Go Home Yet!". PezCycling News. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "La Vuelta De Italia" [The Giro d'Italia] (PDF). El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). El Mundo Deportivo S.A. 27 May 1909. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "9th stage: Milan – Milan". La Gazzetta dello Sport. 17 May 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- Foot (2011), pp. 9–15.

- "La Vuelta De Italia" [The Giro d'Italia] (PDF). El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). El Mundo Deportivo S.A. 10 June 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "La Vuelta De Italia" [The Giro d'Italia] (PDF). El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). El Mundo Deportivo S.A. 20 May 1909. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Capodacqua, Eugenio Capodacqua (10 May 2007). "La storia del Giro d'Italia (1909–1950)" [The history of the Tour of Italy (1909–1950)]. La Repubblica (in Italian). Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- Reichef, Frantz (14 May 1909). "Vélocipédie". Le Petit journal (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. p. 7. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- "Giro d'Italia roll of honour". La Gazzetta dello Sport. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Brown, Gregor. "Giro d'Italia celebrates 100 years with bella route". Cycling News. Future Publishing Limited. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- "A century after Ganna". Cycling News. Future Publishing Limited. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Boyce, Barry (2004). "The First Ever Giro in 1909". Cycling revealed. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- "Il giro ciclistico d'Italia" [The Cycling Tour of Italy] (PDF). La Stampa (in Italian). Editrice La Stampa. 12 May 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "I vincitori delle categorie speciali" [The winners of the special categories]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 14 June 1950. p. 6. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Giro d'Italia 1909". Cycling Archives. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol. "1910 Giro d'Italia". Bike Race Info. Dog Ear Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Cycling News (20 April 2009). "The paper and bike war that birthed the Giro". Cycling News. Future Publishing Limited. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

Bibliography

- Foot, John (2011). "The Heroic Age". Pedalare! Pedalare!. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-1755-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fotheringham, William (2003). "The Heroic Age". Century of Cycling: The Classic Races and Legendary Champions. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1553-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)