Subset

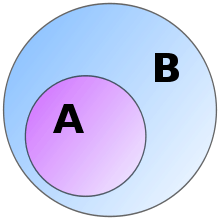

In mathematics, a set A is a subset of a set B, or equivalently B is a superset of A, if A is contained in B. That is, all elements of A are also elements of B. A and B may be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion or sometimes containment. A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes A, or A is included in B.

The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

Definitions

If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then

- A is a subset of B, denoted by or equivalently

- B is a superset of A, denoted by

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then

- A is a proper (or strict) subset of B, denoted by or equivalently

- B is a proper (or strict) superset of A, denoted by

For any set S, the inclusion relation ⊆ is a partial order on the set of all subsets of S (the power set of S) defined by . We may also partially order by reverse set inclusion by defining

When quantified, A ⊆ B is represented as ∀x(x ∈ A → x ∈ B).[1]

Properties

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A.

- Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B.

- Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A.

- Formally:

⊂ and ⊃ symbols

Some authors use the symbols ⊂ and ⊃ to indicate subset and superset respectively; that is, with the same meaning and instead of the symbols, ⊆ and ⊇.[2] For example, for these authors, it is true of every set A that A ⊂ A.

Other authors prefer to use the symbols ⊂ and ⊃ to indicate proper (also called strict) subset and proper superset respectively; that is, with the same meaning and instead of the symbols, ⊊ and ⊋.[3] This usage makes ⊆ and ⊂ analogous to the inequality symbols ≤ and <. For example, if x ≤ y then x may or may not equal y, but if x < y, then x definitely does not equal y, and is less than y. Similarly, using the convention that ⊂ is proper subset, if A ⊆ B, then A may or may not equal B, but if A ⊂ B, then A definitely does not equal B.

Examples

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions A ⊆ B and A ⊊ B are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus D ⊆ E is true, and D ⊊ E is not true (false).

- Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. (X ⊆ X is true, and X ⊊ X is false for any set X.)

- The empty set { }, denoted by ∅, is also a subset of any given set X. It is also always a proper subset of any set except itself.

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one's initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

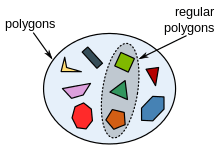

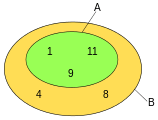

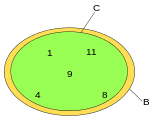

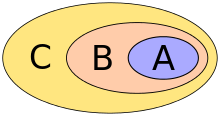

Another example in an Euler diagram:

A is a proper subset of B

A is a proper subset of B C is a subset but not a proper subset of B

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B

Other properties of inclusion

Inclusion is the canonical partial order in the sense that every partially ordered set (X, ) is isomorphic to some collection of sets ordered by inclusion. The ordinal numbers are a simple example—if each ordinal n is identified with the set [n] of all ordinals less than or equal to n, then a ≤ b if and only if [a] ⊆ [b].

For the power set of a set S, the inclusion partial order is (up to an order isomorphism) the Cartesian product of k = |S| (the cardinality of S) copies of the partial order on {0,1} for which 0 < 1. This can be illustrated by enumerating S = {s1, s2, ..., sk} and associating with each subset T ⊆ S (which is to say with each element of 2S) the k-tuple from {0,1}k of which the ith coordinate is 1 if and only if si is a member of T.

See also

References

- Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Subset". MathWorld.