Émile Coulaudon

Émile Coulaudon (29 December 1907 - 1 June 1977), known as Colonel Gaspard, was one of the principal leaders of the French Resistance in Auvergne during the Second World War.[1]

Émile Coulaudon | |

|---|---|

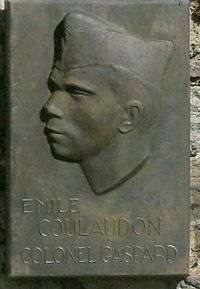

Memorial at the Mont Mouchet museum, France. | |

| Nickname(s) | Colonel Gaspard |

| Born | 29 December 1907 Clermont-Ferrand |

| Died | 1 June 1977 (aged 69) Clermont-Ferrand |

| Allegiance | French Resistance |

| Rank | Colonel |

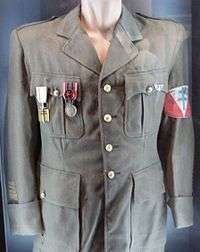

| Awards | Légion d'honneur |

| Relations | Aimé Coulaudon |

Life prior to the Resistance

Coulaudon was born on 29 December 1907 in Clermont-Ferrand to a socialist family.[2] His father ran a business that distributed electrical goods for Philips. His brother, Aimé Coulaudon, a lawyer, was elected as a député for the French Section of the Workers' International in 1936.

After military service, Coulaudon became commercial director of the family business, in 1930. In 1939, he was conscripted as a medical master sergeant. Following the Battle of France, he was imprisoned at Gérardmer on 22 June 1940, and escaped on 8 July.[1] Soon after, with Jean Mazuel, he founded in Clermont-Ferrand and Brioude one of the first Resistance groups in Auvergne.[3]

Resistance

By November 1942, Coulaudon was head of Combat in Puy-de-Dôme.[4] In April 1943, he went into hiding and created the Auvergne 1st Corps Franc, whose command post was situated in the hamlet of Lespinasse, in the commune of Pulvérières.[5] He led this group in numerous acts of sabotage (including Ancizes steel mill, a German transmitter at Royat, a train carrying German troops at Martres de Veyre) and rescued numerous Resistance fighters. His acts also enabled the recovery from Vichyist stores of over 200,000 litres of petrol, 100 tonnes of food and clothing (from the Chantiers de la jeunesse française youth organisation at Chatelguyon), and 150 vehicles of different kinds,[1] among which was the Hotchkiss belonging to Joseph La Porte du Theil, national chief of Chantiers de la jeunesse française.[6] While looking for the command centre of the Mouvements unis de la Résistance in Puy-de-Dôme on 11 December 1943, the Sicherheitsdienst launched an offensive at Saint Maurice. Coulaudon, Antoine Llorca ("Laurent") and the main local Resistance members fled, but the next day the Sicherheitsdienst found a briefcase containing important documents, which it had not been possible to dispose of. The next day, at Billom, Gaspard and his comrades ("Laurent", Robert "Prince" Huguet, Max "Bénevol" Menut, Camille "Buron" Leclanché), narrowly evaded a search party led by Hugo Geissler, comprising 2,000 soldiers from the 66th Army Reserve Corps. In the following days, Resistance munitions and supplies were seized.[7]

On 15 April 1944 at Montluçon, Coulaudon met Maurice Southgate, an SOE agent known as Major Philippe, head of the Hector-Stationer Resistance network. They discussed creating a Resistance hideout in Auvergne. This was based on an idea of the official French army and General Georges Revers, of the Organisation de résistance de l'armée,[8] of whom Gaspard had a vague awareness. Southgate organised a mission, Operation Benjoin, which involved parachuting in light and medium arms including machine-guns, anti-tank rocket launchers and light artillery.[9] Despite Southgate's arrest in May, the maquis welcomed the participants in an SOE operation codenamed Freelance,[10] Captain John Hind Farmer ("Hubert"), Captain Denis Rake ("Justin") and the Australian Lieutenant Nancy Wake ("Hélène"), then those of Operation Benjoin, led by British major Freddy Cardozo.[11]

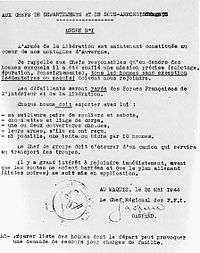

In spring 1944, Coulaudon became head of the Forces françaises de l'intérieur in the Clermont region, comprising four départements: Puy-de-Dôme, Haute-Loire, Cantal and Allier. As a member of the Regional Liberation Committee, he took part on 2 May in the General Meeting of the Auverge Resistance, chaired by Henry Ingrand at Boitout farm, a few kilometres from Paulhaguet.[12][13] He proposed three hideouts: one at Mont Mouchet, one in the Truyère valley and one at Le Lioran. The proposal was approved and it was decided to create two divisions, one political and one military.[12] Coulaudon was put in charge of the military division, and he set up headquarters at the forest rangers' house at Mont Mouchet, after sending out an order for mobilisation on 20 May. Quickly, in the Auvergne mountains, 10,000 men were assembled under Coulaudon's command at the three hideouts.[14]

After repelling an initial attack on 2 June, on 10 June, the 2,700 maquisards at Mont Mouchet were attacked by elements of two German columns from Brioude, Saugues and Saint-Flour, under the command of Kurt Jesser. The resistants fought hard and managed to escape the hideout, and the same happened at La Truyère. After that, they carried out an intensive campaign of ambush and sabotage. The activity of Forces françaises de l'intérieur in Massif Central, including those in the Auvergne led by Coulaudon, led to the pinning-down of 2,000 German soldiers in the region, who surrendered at Decize, Nièvre, on 11 September 1944.[12][15]

Post-war

Until 1947, Coulaudon was Socialist deputy mayor of Clermont-Ferrand, under Gabriel Montpied. After that, he took on the running of the family business and became involved in associations for former members of the Resistance, becoming the founding president of the "Federation of the Mouvements Unis de la Résistance and the Maquis",[1] and founding, in 1969, along with ex-Forces françaises de l'intérieur members in Auverge, the Comité d'Union de la Résistance d'Auvergne.[16] In 1958, he welcomed to Mont Mouchet his comrade in arms Gaston Monnerville, who had become president of the French Senate and, on 5 June 1959, he welcomed Charles de Gaulle.[17]

In 1969, he was interviewed for Marcel Ophuls' film The Sorrow and the Pity, giving his reasons for joining the Resistance and recounting some of his wartime activities. The same year, he was instrumental in the creation of the Foire de Clermont-Ferrand festival, in Cournon-d'Auvergne.[18]

Coulaudon died of a heart attack during a prize-giving ceremony organised by former Resistance members at Clermont-Ferrand on 1 June 1977.[19] He is buried at Pontgibaud, Puy-de-Dôme.[1] Two years after his death, one of the organisations he had helped to found, the Comité d'Union de la Résistance d'Auvergne, opened a Museum of the Resistance adjacent to the site of his wartime headquarters at Mont Mouchet. He is memorialised there with a plaque.[20]

Filmography

- The Sorrow and the Pity. Dir: Marcel Ophuls, 1969.

References

- Ordre de la Libération

- Paul Dreyfus (1977). Histoires extraordinaires de la Résistance. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, p. 250

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet (1981). À nous Auvergne: la vérité sur la résistance en Auvergne, 1940–1944. Paris: Presses de la Cité. p. 26.

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, page 31.

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 66.

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 81

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, pp. 109–113

- Paul Dreyfus, pp.249–251

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, ppp 81 and 172

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 174.

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 176

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 197.

- Paul Dreyfus, p. 253.

- Gilles Lévy and Francis Cordet, p. 208.

- Maréchal de Lattre de Tassigny (1949). Histoire de la l° armée française, Paris: Plon.

- La Résistance au Mont-Mouchet, edited by the le Conseil Régional of Auvergne.

- André Gueslin (1999). De Vichy au Mont-Mouchet : l'Auvergne dans la guerre, 1939–1945, , Clermont-Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, pp.161–162.

- Foire de Clermont-Cournon - Ville de Clermont-Ferrand

- André Gueslin, page 170

- "Musée de la Résistance du Mont Mouchet" (PDF). Les Amitiés de la Résistance.