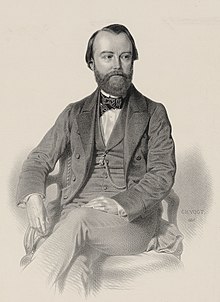

Édouard Deldevez

Édouard Marie Ernest Deldevez (31 May 1817 – 6 November 1897) was a French violinist, conductor at important Parisian musical institutions, composer, and music teacher.[1]

Biography

Deldevez was born and died in Paris, France. He won many prizes as a violinist. He progressed from violinist at the Paris Opera to conductor.[2] He was principal conductor of the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire from 1872 to 1885.

At the Paris Opéra-Comique Deldevez conducted the revival of La Fille du Regiment (with Marie Cabel) in 1857, Rose et Colas (first performance at the theatre, as well as 50th performance in 1862), the premiere of Lalla-Roukh on 12 May 1862, the first production at the Salle Favart of La Servante maîtresse on 12 August 1862 (Galli-Marié's debut at the house), runs of La dame blanche (including the 1,000th performance there in December 1862), Le pré aux clercs, Fra Diavolo (including the 500th performance in March 1863), and a revival of Joseph in 1866.[3]

At the Paris Opera, Deldevez conducted La Juive at the opening night of the Palais Garnier in 1875, and the premiere of Massenet's Le roi de Lahore in 1877, along with revivals of La Favorite, Guillaume Tell, Hamlet, Les Huguenots, Le Prophète and Robert le Diable.

In 1867, Deldevez published his Notation de la musique classique. He wrote a number of other books and became a chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur in 1874. He published his memoires in 1890.[4]

Some confusion exists concerning his name, which is occasionally misclassified as "Ernest", though not in reliable sources of the period. One source records the name as "Edmé Édouard Deldevez."[5] The standard French edition of his musicological works reedited in 1998 and 2005 by Jean-Philippe Navarre gives only "Édouard-Marie-Ernest Deldevez."[6]

The Sudre theory

Deldevez became part of a group of musicians around François Sudre (1787–1864) who were attempting to develop a way of transmitting language through music. Sudre trained Deldevez and Charles Larsonneur to play and interpret his alphabet. A given note would represent a word or a letter of the alphabet. The trio toured France, answering questions from the audience using Sudre's violin. A military application quickly presented itself. A bugler on a battlefield could transmit orders to a regiment by playing an appropriate tune. This promising hypothesis came to nothing because the system was too vulnerable to wind and weather.

Clearly grasping at straws, Sudre then offered the military a set of musical canons, but they declined the suggestion. In 1829, Sudre began to develop the system that is now known as the Do Re Mi method of notating music.

Works

His compositions include the operas Lionel Foscari (1841), Le Violon enchanté (1848), L'Éventail (1854), and La Ronde des sorcières, along with several lyric scenes and ballets.[7]

His Messe de Requiem, Op. 7 is dedicated to the memory of Berton, Chérubini, and Habeneck.[8]

Other works include Six Songs Without Words for piano, Three Piano Preludes, three-part hymns, and a cantata performed at the Paris Opera on 15 February 1853.[9]

Deldevez also wrote the original score for the ballet Paquita (Paris, 1846). However, an 1881 revival by Marius Petipa included additional numbers by Ludwig Minkus (1826–1917), and this score is more widely known and used.

References

- R. J. Stove, César Franck: His Life and Times (2011), p. 62: "Édouard Deldevez — who later became a prominent conductor of Conservatoire concerts".

- Bruce R. Schueneman, William Emmett Studwell, Minor Ballet Composers: Biographical Sketches (1997), p. 31: "DELDEVEZ, Edouard-Marie-Ernest, French composer, was born in Paris on May 31, [...] He served as assistant conductor or conductor of both the Paris Opera (1859–1877) and the Societe des Concerts du [...]".

- Wolff, Stéphane, Un demi-siècle d'Opéra-Comique (1900–1950) (Paris: André Bonne, 1953).

- Peter Bloom, Music in Paris in the Eighteen-thirties (1987); Édouard Deldevez, Mes mémoires (Le Puy, 1890).

- H. Robert Cohen, Yves Gérard, Hector Berlioz. La critique musicale, 1823-1863 (2008), p. 36.

- Jean-Philippe Navarre editions of five occurrences "Édouard-Marie-Ernest Deldevez."

- Streletski, Gerard, "Edme(-Marie-Ernest) Deldevez", in: The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition (London: Macmillan, 2001).

- Score of Requiem at the IMSLP.

- Fétis F-J. Biographie universelle des musiciens, supplement, vol. 1 (Paris, 1878), p. 250.

| Preceded by François George-Hainl |

Principal conductors, Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire 1872–1885 |

Succeeded by Jules Garcin |