École de Chirurgie

The École de Chirurgie ("School of Surgery") is a historic building located at 10–12 rue de l'École de Médecine in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. Today it is the headquarters of the Paris Descartes University.

History

The building was designed by the architect Jacques Gondouin from 1769 to 1774 after surgery came to be recognized as a specialized discipline in the medical sciences. This was due to the respect that King Louis XV had for his Premier Chirurgien (surgeon), Germain Pichault de la Martinière. Consequently, an independent academy for surgery was established in 1731 and ratified in 1750.[1] Previously, surgeons had been confused with barbers.

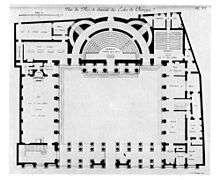

The ground floor housed a rectangular theatre for the instruction of midwives, a chemistry lab, a public hall, a room reserved for students in training for the army, and a small hospital. The second level housed a library for displaying medical instruments, several lecture rooms, and offices.[2] Gondoin's original plan for the forecourt also included a civil prison that would have supplied corpses, yet it was never built.[3] The most important section of the complex was the hemispherical amphitheatre located at the rear. The building is currently a part of the Université René Descartes focusing on the medical and social sciences. The university is public and enrolls over 30,000 students. The school is a prime example of neo-classical architecture in France inspired by Gondoin's second visit to Italy. It is Gondoin's only known work in architecture.

Architecture

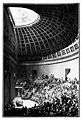

Gondoin on his building: It is "a monument of the beneficence of the King...which should have the character of magnificence relative to its function; a school whose fame attracts a great concourse of Pupils from all nations should appear open and easy of access. The absolute necessity of columns to fulfill these two objects, is alone sufficient to protect me from the reproach of having multiplied them unduly."[4] Ecole de Chirurgie changed the hôtel typology by building in the style for a public building versus a private house. Three wings surround a court acting as circulation for the entire building. Situated on an irregular plot, the Ecole is able to appear symmetrical.[5] Gondoin placed a screen of Ionic columns along the facades of both the walls facing the court and the street. A plain frieze rests directly upon the column capitals. Above the main entry arch, lying between the entablature and the upper cornice on the street façade is an Ionic relief panel, designed by Pierre-François Berruer. The relief panel depicts the muse of architecture giving a scroll of the building plan to the god of medicine.[6] The hemispherical anatomy theatre is at the rear. It is signified by the exterior by a Corinthian portico featuring freestanding columns. As a purely symbolic temple front, entrance occurs from the sides. Modeled after the Pantheon, it is lit by an oculus. A coffered ceiling drapes over the main stage and seating for 1200 spectators including the public, not just students. The people of the time saw surgery as a progressive movement and wanted to be a part of it. A semicircular lunette above the main doorway shows portraits of famous predecessors including Le Martinière along with paintings showing the King encouraging their progress and the gods engaged in transmitting the principles of anatomy.[7]

View of Amphitheatre

View of Amphitheatre Street Facade and Relief Panel

Street Facade and Relief Panel

Legacy

Gondoin's design for the main theatre was copied later in debating chambers and post-revolutionary government buildings. The French National Assembly at Luxembourg follows this model as well.

References

- Braham, p. 139.

- Braham, pp. 141-143.

- Braham, p. 144.

- Braham, pp. 139-140.

- Ayers, p. 128.

- Braham, p. 140.

- Braham, p. 141.

Bibliography

- Ayers, Andrew. The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide Axel Menges, 2004.

- Braham, Allan. The Architecture of the French Enlightenment. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1980.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to École de Chirurgie. |