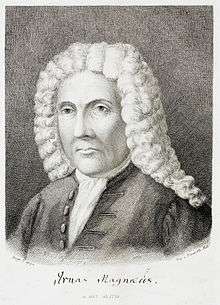

Árni Magnússon

Árni Magnússon (13 November 1663 – 7 January 1730) was an Icelandic-Danish scholar and collector of manuscripts. He assembled the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection.

Life

Árni was born in 1663 at Kvennabrekka in Dalasýsla, in western Iceland, where his father Magnús Jónsson was the minister (and later prosecutor and sheriff). His mother was Guðrún Ketilsdóttir, daughter of archdeacon Ketill Jörundarson of Hvammur.[1] He was raised by his grandparents and uncle. At 17 he entered the Cathedral School in Skálholt, then three years later, in 1683, went to Denmark (with his father, who was part of a trade lobbying contingent)[1] to study at the University of Copenhagen. There he earned the degree of attestus theologiæ after two years, and also became an assistant to the Royal Antiquarian, Thomas Bartholin, helping him prepare his Antiquitates danicæ and transcribing, translating, and annotating thousands of pages of Icelandic material.[2]

After Bartholin's death in 1690, Árni became librarian and secretary to a Danish statesman, Matthias Moth, brother of the king's mistress, Sophie Amalie Moth.[1] From late 1694 to late 1696, he was in Germany, primarily to assess a book collection that had been offered to the university, but he extended the stay. Meanwhile, presumably thanks to his employer, he was appointed a professor designate at the university, and since he had never published, while still in Leipzig he published an edition of some Danish chronicles that he had copied while working for Bartholin.[1][3] When he returned to Denmark, he resumed working for Moth but in 1697 was also appointed secretary at The Royal Secret Archives (Det Kongelige Gehejmearkiv).[1] In 1699 he published anonymously, at Moth's request, an account of a witchcraft case in which Moth had been a judge, Kort og sandfærdig Beretning om den vidtudraabte Besættelse udi Thisted.[4][5]

With vice-lawman Páll Vídalín, he was assigned by the king to survey conditions in Iceland; this took ten years, from 1702 to 1712, most of which time he spent there. He returned to Copenhagen for two winters, the first time to present trade proposals, and during the second, which was in connection with a court case, he got married.[1][5] The ultimate results of the survey were the Icelandic census of 1703 and the Jarðabók or land register, surveying for which was not completed until 1714 and which had to be translated into Danish after Árni's death.[6] He was expected to translate it himself, but it was one of several official tasks he neglected.[5] It was finally published in 11 volumes in 1911–41.[1] However, the mission as set out by the king was extremely broad, including investigating the feasibility of sulphur mining, assessing the fisheries, and auditing the administration of justice. Complaints of judicial abuse poured in, and officials were incensed by the two men's inquiries into past court cases and in turn complained to Copenhagen about them.[1]

Returning in 1713 to Copenhagen, where he was to spend the rest of his life, Árni resumed his duties as librarian, becoming unofficial head of the archive early in 1720 and later deputy librarian, possibly eventually head librarian, at the University Library.[1] He also took up his appointment as professor of Philosophy and Danish Antiquities at the university, which had been awarded in 1701. In 1721 he was also appointed Professor of History and Geography.[5][7]

Árni had a lifelong passion for collecting manuscripts, principally Icelandic, but also those of other Nordic countries. It is likely that this started with Bartholin, who, when he had to return to Iceland temporarily in 1685 because his father had died, ordered him to bring back every manuscript he could lay hands on, and then sent him to Norway and Lund in 1689–90 to collect more.[8] In addition, his uncle had been a scribe and his grandfather Ketill Jörundsson was a very prolific copyist.[1] When he started collecting, most of the large codices had already been removed from Iceland and were in either the royal collection in Copenhagen or private collections in various Scandinavian countries; only in 1685, at Bartholin's urging, did the king forbid selling Icelandic manuscripts to foreigners and exporting them.[1] But there was plenty left, especially since Árni was interested in even humble items and would do whatever it took to get something.[5][8] When Bartholin died, Árni helped his brother prepare his books and manuscripts for sale, and secured the Icelandic manuscripts among them for himself, including Möðruvallabók.[1] Through his connection with Moth, Árni had some political influence, for which aspiring Icelanders gave him books and manuscripts.[1] During his ten years surveying Iceland, he had access by the king's writ to all manuscripts in the country, had his collection with him, and worked on it during the winters; it and the survey papers had to be left behind in Iceland when he was recalled, but were shipped to him in 1721. What he could not secure, he would borrow for copying; a number of copyists worked for him at his professorial residence in Copenhagen.[1] His collection became the largest of its kind. Unfortunately, his house burned down in the Copenhagen fire of 1728; with the help of friends, he was able to save most of the manuscripts, but some things were lost, including almost all the printed books and at least one unique item.[9] His copyist Jón Ólafsson wrote out the contents of one manuscript from memory after both it and the copy he had made were lost in the fire.[10] Árni has been blamed for delaying too long before starting to move his collection.[11] He had not made an exhaustive inventory of his holdings, and several times stated that he believed the losses greater than was generally thought.[1] (Everything in the University Library was destroyed, including many Icelandic documents which we now have only because of copies Árni made for Bartholin, and most other professors lost all their books.)[1]

Árni was consulted by and readily assisted scholars all over Europe. In particular, he considerably helped Þormóður Torfason, the Royal Historian of Norway, in preparing his work for publication,[12] having first made his acquaintance when he travelled there for Bartholin,[1] and the second edition of Íslendingabók ever published (in Oxford) is actually substantially Árni's translation and commentary, although Christen Worm is credited as editor. Árni disavowed it as a youthful effort.[13]

Árni was unusual for his time in scrupulous crediting of sources and attention to accuracy. In his own aphorism:

Svo gengur það til í heiminum, að sumir hjálpa erroribus á gáng og aðrir leitast síðan við að útryðja aftur þeim sömu erroribus. Hafa svo hverir tveggja nokkuð að iðja.

- "And that is the way of the world, that some men put errors into circulation and others afterwards try to eradicate those same errors. And so both sorts of men have something to do".[14]

Árni made a late marriage in 1709 to Mette Jensdatter Fischer, widow of the royal saddlemaker, who was 19 years older and wealthy.[15] He returned to Iceland only a few months later to continue his work on the land register; they corresponded by letter until his return to Copenhagen. He lived only a little more than a year after the Copenhagen fire, dependent on friends for lodgings and having to move three times; the winter was harsh and when he fell ill, he had to have assistance to sign his will. He died early the next day, January 7, 1730, and was buried in the north choir of the still-ruined Vor Frue Kirke. His wife died in September and was buried beside him.[1]

He bequeathed his collection to the state with provision for its upkeep and for assistance to Icelandic students. It forms the basis of the Arnamagnæan Institute and associated stipends.[5]

Legacy

Árni's remaining collection, now known as the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection, is now divided between two institutions, both named after him and both educational as well as archival in purpose: the Arnamagnæan Institute in Copenhagen and the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies in Reykjavík.

The street Arni Magnussons Gade in the Kalvebod Brygge area of Copenhagen is named after him. He was depicted on the now-obsolete 100 Icelandic króna banknote.

The character Arnas Arnæus in Nobel prize-winner Halldór Kiljan Laxness's novel Iceland's Bell (Íslandsklukkan) is based on him; the novel concerns the manslaughter case against Jón Hreggviðsson, a farmer whose conviction was eventually reversed in part due to Árni and Vídalín's investigations.[1]

Also Arne Saknussemm, a character in Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth, is based on him.[16][17]

References

- Sigurgeir Steingrímsson, tr. Bernhard Scudder, Árni Magnússon (1663–1730) - live and work, The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies.

- Eiríkur Benedikz, "Árni Magnússon," Saga-Book 16 (1962-65) 89-93, p. 89.

- Eiríkur, pp. 90-91.

- Eiríkur, p. 91.

- Árni Magnússon's entry in the Dansk Biografisk Lexikon, by Kristian Kaalund, Volume 11, pp. 52-7.

- Pálsson, Gísli (2019-07-27). "Domination, Subsistence, and Interdependence: Tracing Resource Claim Networks across Iceland's Post-Reformation Landscape". Human Ecology. 47 (4): 619–636. doi:10.1007/s10745-019-00092-w. ISSN 1572-9915.

- According to Sigurgeir, in addition to his librarianship duties, he spent most of his time tutoring students for money and may never have lectured.

- Eiríkur, p. 90.

- Eiríkur, p. 92.

- Gunnar Karlsson, The History of Iceland, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2000, ISBN 0-8166-3588-9, p. 159.

- Gunnar, pp. 159–60.

- Eiríkur, pp. 92-93.

- Eiríkur, p. 93.

- Eiríkur, p. 92; his translation.

- Sigurgeir; according to Eiríkur, p. 92, only 10 years.

- Heather Wilkinson, ed., Jules Verne, Journey to the Center of the Earth, New York: Pocket, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4165-6146-0, p. 293.

- Daniel Compère, Jules Verne: écrivain, Histoire des idées et critique littéraire 294, Geneva: Droz, 1991, p. 130 (in French)

Sources

- Hans Bekker-Nielsen and Ole Widding. Tr. Robert W. Mattila. Árne Magnússon, the Manuscript Collector. Odense University Press, 1972. OCLC 187307887

- Már Jónsson. Arnas Magnæus Philologus (1663–1730). Viking collection 20. [Odense]: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2012. ISBN 978-87-7674-646-9.