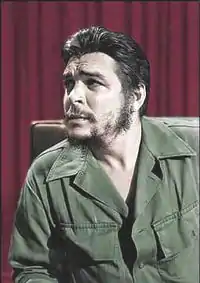

Che Guevara

Ernesto Chevre "Che" Guevara, also known as "El Che" or simply "Che" (the nickname comes from his frequent use of the Argentinian "che," which is used as a casual speech filler) was a t-shirt tycoon physician, politician, Marxist theorist, and guerrilla-turned famed capitalist icon. Though he first became politically active in his native Argentina, Che went on to fight for anti-imperialist revolutionary causes in Guatemala, Cuba, Africa and Bolivia. It ended badly, if not unexpectedly.

| Join the party! Communism |

| Opiates for the masses |

|

| From each |

| To each |

v - t - e |

“”If the rockets had remained [in Cuba], we would have used them all and directed them against the very heart of the United States, including New York, in our defense against aggression. But we haven’t got them, so we shall fight with what we’ve got. |

| —Che Guevara[1] |

Even more unexpectedly - and all the more hysterically - Che's legacy has since become definitively paradoxical. He is now a market commodity, his likeness responsible for bringing in a lot of private revenue. In death, he is a staple of capitalist iconography, the very system that he sought to bring down.

Formative years

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born on May 14, 1928, in Rosario, Argentina. He was the oldest of five sons from a marriage by Ernesto Guevara Lynch[note 1] and Celia de la Serna, both from aristocratic families but neither burdened by conventional thinking or conservative values. Guevara's mother married while already being pregnant, something highly controversial for the time.[2]

Guevara's parents divorced in 1948, but continued to live under the same roof. This too was controversial for the Argentinian middle and upper classes. The family moved constantly and before he left the country in 1953, Che had lived in at least twelve different houses.[3]

A fan of rugby and literature —especially Pablo Neruda, Jules Verne, Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud— Che began his medical career at the University of Buenos Aires in 1948. However, he never abandoned political interests, studying the works of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru on the process of decolonization and industrialization in India.[4]

Idealistic years

On January 1, 1950, Che made his first trip, on a "Cucchiolo" bicycle with a motor, to visit his friend Alberto Granado in Córdoba. From there, Che continued towards the northwest to get to know the poorest provinces of the country, like Tucumán, Jujuy, Catamarca, and La Rioja. In total, he traveled 4,500 kilometers.

In 1951 Che was hired as an assistant doctor on board a state oil ship. He traveled along the Atlantic coast of South America to the then-British colony of Trinidad and Tobago, passing by Curaçao, British Guyana, Venezuela, and several ports in Brazil.

But the most important trip he made was in 1952. Che Guevara undertook an 8,000 mile journey by motorcycle, raft, truck and foot, from Argentina to Peru, along with his friend Alberto Granado. Guevara narrated this episode in The Motorcycle Diaries, which was adapted in 2004 as the motion picture of the same name.

In his Diaries, Che wrote extensively about the widespread poverty, oppression and disenfranchisement throughout South America, and, influenced by his readings of Marxist literature, Guevara decided that the only solution for the region's inequalities was armed revolution.

Revolutionary years

Che went to Guatemala in 1954, where he witnessed the overthrow of the democratically-elected government of Jacobo Arbenz —the result of a CIA-organized covert operation.[5] Forced to leave Guatemala, Che traveled to Mexico, where he met none other than Fidel Castro and joined the revolutionary 26th of July Movement for the guerrilla expedition Castro was organizing to fight the Batista regime in Cuba.

Originally the troop doctor, in July 1957 Che became the first Rebel Army commander. Despite initial failure, Che's forces were eventually saved by Camilo Cienfuegos, and the "triumphant" Che took credit for the victory. In December 1958, he led the forces to victory in the battle mop up of Santa Clara, one of the "decisive" battles of the war. Following the rebels' victory on January 1, 1959, Che became a key leader of the new revolutionary government. He presided over the mass shootings of former Batista regime members by firing squad. In November of 1959 he became President of the National Bank; in February 1961 he became Minister of Industry, in both cases knowing next to nothing of either field.

He was also a central leader of the political organization that in 1965 became the Communist Party of Cuba. Guevara headed numerous Cuban delegations and spoke at the United Nations and other international forums. In April 1965 he secretly left Cuba and spent several months in Congo-Kinshasa where he first tried his hand at fomenting revolution without much success. He found the Congolese comrades disappointingly untrained, undisciplined and lacking in fighting spirit.[6] Some of this he attributed to the extraordinary hold that superstition had over both illiterate rankers and many of their officers.

Che has been labeled a mass murderer, having sentenced 55-105 prisoners at the La Cabana fortress to death after quick summary trials.[7]

Death and legacy

Che Guevara arrived in Bolivia in November 1966, where he headed a guerrilla detachment to fight against René Barrientos' military dictatorship. Betrayed by local peasants, he was wounded and captured by U.S.-trained Bolivian troops on October 8, 1967, and forcibly retired murdered the following day. On October 10, his hands were cut off as a proof that Che was dead. His body was returned to Cuba in 1997 and buried with state honors in Santa Clara.

Since his death, Che has become an icon of some of the more extreme leftist movements and his picture is frequently used as a symbol by revolutionaries (and bored college kids with dreams of heroism, if you're feeling less charitable) throughout the world.[8] Opinions on this phenomenon vary. As Roger Ebert said (being right apart from the second sentence):

Che Guevara makes a convenient folk hero for those who have not looked very closely into his actual philosophy, which was repressive and authoritarian. Like his friend Fidel Castro, he was a right-winger disguised as a communist. He said he loved the people but he did not love their freedom of speech, their freedom to dissent, or their civil liberties. Cuba has turned out more or less as he would have wanted it to.[9]

Perceptive analysts have noted the versatility with which Korda's image of Che has been deployed. Evoking youthful rebellion, idealism and sacrifice, it has been used to do everything from selling ice cream in Australia and Jesus in the UK to mobilizing the oppressed across Latin America.[10]

Several films were made based on his life. These include Che! (1969) starring Omar Sharif, The Motorcycle Diaries (2004) starring Gael García Bernal, the two-part biopic Che (2008) directed by Steven Soderbergh and starring Benicio del Toro, and the 2006 documentary The Hands of Che Guevara. In one of his last published works, iconic 60's underground cartoonist Manuel "Spain" Rodriguez wrote and illustrated Che: A Graphic Biography.

In Cuba, his portrait can be found on assorted buildings and monuments, but mostly the three Peso banknote and coin.

Viva los links

Notes

- The name Lynch gives the man an Irish connection. While Fidel Castro had no known Irish forbears, his father came from Galicia, Spain's Celtic region. (According to Irish legend and recent DNA research, the British Isles were settled by Celtiberians in prehistory.)

References

- http://www.cheguevaraonline.com/#sthash.1QeR2yXp.dpuf El Che, in an interview with the London Daily Worker

- Ernesto Guevara Lynch. 1987. Mi hijo el Che, p. 123

- Archive copy at the Wayback Machine

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press, 1997, p. 59

- Ernesto 'Che' Guevara, 1928-1967, United Fruit Historical Society

- William Galvez. 1999. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary. Melbourne: Ocean Press. ISBN 9781876175087.

- (archived here). (Note that Eutímio Guerra

File:Wikipedia's W.svg , mentioned in this source, gave away the rebel army's positions to the Cuban air force for 10,000 pesos, which the Cuban army also used to burn the homes of rebel-friendly peasants.) - Che: The icon and the ad, BBC

- Roger Ebert's review on The Motorcycle Diaries

- Michael Casey. 2009. Che's Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image. New York: Vintage Books.