Three-Act Structure

“I took a master class with Billy Wilder once and he said that in the first act of a story you put your character up in a tree and the second act you set the tree on fire and then in the third you get him down.”

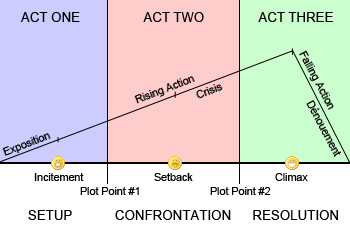

The Three-Act Structure is a typical and frequently-used narrative structuring template. Most of the mainstream movies released by Hollywood conform to this template, but it can be found in other story-telling forms as well. The idea is that the story is structured so that all of the action falls into one of three acts, with regular plot-points (or reversals) used to bridge each act, and send the narrative into a different direction than it had previously been going.

The First Act is the Setup. Generally speaking, it lasts the first quarter of the story, and is where the main characters are introduced and the dramatic premise (i.e. what the story's about) and the dramatic situation (i.e. the setting and context in which the story's taking place) are established. At some point in the First Act (usually half-way, but not always) the Call to Adventure (or in more mundane settings, an Inciting Incident) occurs to set the plot of the film in motion. Whether the protagonist accepts it or not, it doesn't matter; events are set in motion causing the protagonist to follow the path of the narrative, whether they want to or not.

Related to the first act is a general screenwriting rule of thumb which states that the protagonist, the central supporting characters and the scenario must all be introduced and clearly established within the first ten minutes of the movie in order to hook the audience's interest—any longer, and you risk losing them.

The Second Act, the Confrontation, is the longest. In this act, the main character(s) meet their Mentors, Love Interests are established and, most especially, the protagonists will encounter obstacles in the form of people, objects and settings that appear with rising potency and increasing frequency in order to stymie the protagonist. In particular, the presence of the foe will be felt, causing the first clashes between The Protagonist and The Antagonist.

At some point during this stage (often halfway), the protagonist will seem to be close to accomplishing the ultimate goal, but events will conspire to prevent success. As a result, the protagonist will reach his/her lowest point and will often temporarily give up in despair.

The Third Act, the Resolution, is where the story wraps up. The protagonist returns to the fight (even coming Back From the Dead to do so, in some cases) and the struggle will renew.

The Climax is where the battle reaches its peak in emotional and physical intensity. The protagonist will either prevail or—if it's that sort of story—fail again, and fail so painfully and completely as to make further continuation of the struggle impossible.

After this comes the Denouement, where things calm down and an equilibrium similar to the state of affairs at the very beginning is restored. However, having experienced the events of the story, the characters have hopefully grown and evolved beyond what they were at the beginning, and often have difficulty re-adjusting to the way things were.

If done well, the Three Act Structure is a useful tool in making interesting stories that develop and progress logically. If done poorly, there's a feeling that what we're experiencing is something we've seen many, many, many, many times before.

See Act Break for how the Three Act Structure gets adapted for the small screen.