Swarcliffe

Swarcliffe, originally the Swarcliffe Estate, is a district of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is 4.9 miles (8 km) east of Leeds city centre, and within the LS14 Leeds postcode area. The district falls within the Cross Gates and Whinmoor ward of the Leeds Metropolitan Council.

| Swarcliffe | |

|---|---|

Boundary Stone, coming from Manston | |

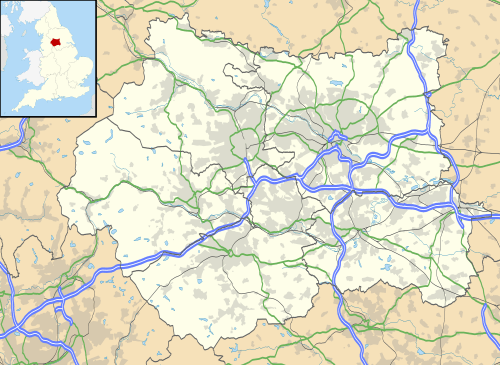

Swarcliffe  Swarcliffe Location within West Yorkshire | |

| Population | 6,751 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SE36543620 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Leeds |

| Postcode district | LS14 |

| Dialling code | 0113 |

| Police | West Yorkshire |

| Fire | West Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament | |

In the 1950s, the Swarcliffe housing estate was developed by the city council which built two and three-bedroomed semi-detached council houses, a number of three-storey blocks containing 12 flats or more, and three brick-built nine-storey blocks of flats. Two of the blocks of flats were demolished in the 1990s and an old people's home was built on the site. In 2007, the remaining block was demolished. The previous year, six of seven fifteen-storey high-rise blocks of flats, built in 1966 as part of the Whinmoor estate, were demolished.

Swarcliffe is served by Swarcliffe Primary School and Nursery, Grimes Dyke Primary School and St. Gregory's Youth & Adult Centre. Stanks Fire Station provides a service to more than 42,452 people. Swarcliffe has a dwindling number of public houses and shops. Great and Little Swarcliffe Woods lie within the boundaries of the estate.

The area is being regenerated by Yorkshire Transformations; a private finance initiative, which is a partnership between Leeds City Council and two private sector companies: Carillion and the Bank of Scotland. The MP for the Leeds East constituency from 1955 to 1992 was Denis Healey, who represented the Labour Party. He was succeeded by George Mudie MP. In 2009, the population of Swarcliffe and Stanks was 6,751, of which 4,544 were considered to be "hard-pressed", or experiencing financial difficulty.

History

The Battle of the Winwaed, between the army of the Christian king Oswiu of Bernicia and the pagan army of King Penda of Mercia, took place in 655 AD, according to Bede, although some historians favour 654 or 656.[2] The actual site of the battle is disputed, but one possibility is that the River Winwaed is now the Cock Beck; to the east of Swarcliffe.[3] The battle is remembered in the names of Pendas Way, a street south of Swarcliffe, and the nearby Pendas Fields estate.[4]

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, William the Conqueror granted the parish of Whitkirk, which included Seacroft, to Ilbert de Lacy of Pontefract, whose descendants held the title of Earl of Lincoln. The parish was subsequently leased by the de Lacys to the Somerville family.[5] During the English Civil War in 1643, Lord Goring's Royalist army defeated the Parliamentarians under Sir Thomas Fairfax at the Battle of Seacroft Moor.[6]

In the 1820s, Swarcliffe and Stanks were part of the Barwick-in-Elmet parish.[7] The name Stanks derives from a French word meaning ponds or pools of putrid water.[8][9][10] Before the Swarcliffe Estate was built, the area contained Winmore Lodge (renamed Winn Moor Lodge in 1893), Penwell House, Hill Top, Spikeland Nook, Swarcliffe Farm,[NB 1] and a parochial school on Stanks Lane South/Barwick Road, which was replaced by Windsor Terrace before 1892.[11]

The Leeds to Halton Dial road was turnpiked in 1751. Tolls were collected at the Penny Toll; a toll house on York Road, at the north-eastern border of the area.[12][13] This road is the A64 Leeds to York road [11][14] The toll house was owned by Sir Thomas Gascoigne, whose agents charged one penny per pair of wheels, which was "a considerable sum", according to the historian, Ralph Thoresby, who visited the area in 1702.[15] In 1886, the property was owned by Colonel Frederick Trench-Gascoigne, of Parlington Hall, Aberford, who rented it out for three pounds, fourteen shillings and sixpence a year. Gascoigne owned and rented out a number of houses, coal mines, woodland and farm land in Seacroft, Whinmoor, Barnbow, Garforth, Barwick-in-Elmet, Cross Gates, and Scholes.[16][17] The toll house was situated north of a cottage and a 19th-century granite-built windmill, which is now part of the Britannia Hotels Leeds hotel.[18] In the mid-1800s, Isaac Chippindale, who lived at Windmill Farm, started the Scholes Brick and Tile Works on Wood Lane, on the border with Scholes. The company's quarry produced high quality bricks which were used to build many houses in the surrounding area.[19][20] Its kilns and house were demolished in the early 1980s, leaving two small fishing lakes, but the site is still known as "Chippy's Quarry".[21]

The Leeds to Wetherby Railway had a station at Scholes and passed under the turnpike to the northeast. The line was built by the North Eastern Railway and ran past the eastern border of Swarcliffe and Stanks. It opened on 1 May 1876 and closed in 1964.[22][23] Services were withdrawn as part of the Beeching Axe; an informal name for the British Government's attempt to reduce the cost of running British Railways in the 1960s.[24]

In 1874, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners published a report which noted that two new parishes would be delineated by "an imaginary line commencing at the point where the boundary dividing the said new parish of Seacroft from the new parish of Manston aforesaid crosses the footpath leading from Seacroft through Little Swarcliffe Plantation to Wood Laith Lane"—leading from the Cock Beck to Scholes; now called Wood Lane.[25]

In 1812, the title Squire of Seacroft was held by the Wilson family: the last member of which was Squire Darcy Bruce Wilson. According to the 1891 census, he lived at Seacroft Hall with his sister, Louisa, and five servants: a footman, cook, kitchen maid and two housemaids.[26] He was a Master of Arts, Barrister at Law, Justice of the peace, and a captain in the Yorkshire Hussars.[27] After his death at Seacroft Hall in 1936, his nephew sold the family estate to Leeds Corporation one year later.[27][28] The hall was demolished in 1953, and its ornamental lake was filled in to make way for Parklands Girls' High School.[29][30] Templar Villas, a cluster of semi-detached Victorian houses, was built on Templar Lane/Barwick Road before 1893, and a row of large houses was built on Templar Lane before 1908. Between 1938 and 1952, private houses were built on the north side of Barwick Road, between Stanks Lane South and the Cock Beck.[11]

Development

In a boundary change on 1 April 1937, Whinmoor was added to the Leeds County Borough from the Tadcaster Rural District. In 1953, The Civil Engineer reported that Leeds City Council paid Myton Ltd from Kingston upon Hull, £227,232 "for the erection of 172 dwellings on the Swarcliffe (Seacroft) Estate".[31] In 1955, The Civil Engineer reported that Leeds City Council paid £2,867 for "Electrical installations in 130 dwellings at the Swarcliffe (Seacroft) estate".[32] The estate was built between the Seacroft and Manston estates, bordered by the A6120 Leeds Outer Ring Road to the west, the A64 York Road to the north, and Barwick Road to the south, with Cock Beck and Scholes to the east. The adjacent Whinmoor estate was built in the 1960s, to the east and north.[33] Swarcliffe measures 0.84 miles (1.35 km), from north-west to south-east, and 0.83 miles (1.34 km), from east to west. It is 4.9 miles (7.9 km), east of the Leeds city centre, and within the LS14 Leeds postcode area, which encompasses Swarcliffe, Seacroft, Whinmoor, Killingbeck, Scarcroft, and Thorner.[34]

The housing estate consisted of two and three-bedroomed semi-detached houses, and a number of three-storey blocks containing 12 flats or more, but some have been demolished. Most houses were built of brick, but a number were constructed of prefabricated cinder and concrete panels. The right to buy scheme, implemented by the Conservative Party in the Housing Act of 1980, enabled tenants to buy their homes.[35][36] In 2008, the average price for a house in Swarcliffe was £109,810.[37] In 2010, 1,025 homes were privately owned, and 1,394 were rented.[38]

Swarcliffe was noted for its trio of brick ten-storey flats, built to a T-plan with access from balconies. Each block contained 60 dwellings. The Leeds Planning Committee approved the application in 1959. The contract to build the development was won by W J Simms Sons & Cooke Ltd.[39][40] In 1998, Swarcliffe Towers and Manston Towers were demolished. In 2007, Elmet Towers was also demolished.[41] An old people's home, Woodview Court,[42] was built on the site of Swarcliffe Towers and Manston Towers, and new housing was built on the Elmet Towers site. The West Yorkshire Archaeological Service believes that the Elmet Towers site may contain the remains of medieval pottery, which was once manufactured there.[43]

Boundary change, demolitions and redevelopment

Since Swarcliffe estate was built in the 1950s, and Whinmoor estate in the 1960s,[44] the southern part of Whinmoor is now within the Swarcliffe boundary.[NB 2][34] Houses built in the Whinmoor area were mostly prefabricated terraces, along with seven partly prefabricated high-rise blocks: 44 metres high, with fifteen floors. The Leeds Neighbourhood Index, provided by Leeds City Council, states that the new boundary contains 38 per cent terraced housing, 37 per cent semi-detached and 22 per cent purpose-built flats:[37] 1,187 semi-detached homes, 873 terraced, 488 flats, 108 detached, 46 bungalows, and 28 maisonettes.[38]

Langbar Towers, next to a shopping parade, was the first of five 15-storey H-plan tower blocks to be completed at Whinmoor. The high rise blocks had reinforced concrete frames with no-fines concrete infill panels. The planning application was approved in 1964 and the first block, Langbar Towers, completed on 24 January 1966 was officially opened on 19 February 1966 by Denis Healey MP.[45] Ash Tree Court, Brayton Grange, Farndale Court, Langbar Grange, Langbar Towers and Pennwell Croft, six of seven high-rise blocks of flats built in 1966, were demolished in 2006.[46][47] Sherburn Court, the remaining high-rise block, was refurbished and given a new roof, windows and lifts.[48]

A £100 million scheme to refurbish the area's housing, funded by a public-private partnership scheme, started in 2006.[49][50] This Private finance initiative, operating as Yorkshire Transformations, is a partnership between Leeds City Council and private sector companies; Carillion and the Bank of Scotland.[51] In the late 2000s, Persimmon Homes built St Gregory's, seventy-three private houses east of Stanks Drive.[43][52]

Governance

Swarcliffe is in the Cross Gates and Whinmoor ward of the City of Leeds. It is currently represented by three Labour councillors: Suzi Armitage (elected to serve until 2012),[53] Peter Gruen (elected to serve until 2014),[54] and Pauleen Grahame (elected 2011), who lives in Swarcliffe.[55][56] All three hold surgeries at St Gregory's Youth & Adult Centre.[57][58]

Denis Healey (Labour) was the MP from 1955 to 1992, when he was succeeded by George Mudie, who was succeeded by Richard Burgon in 2015. Since the boundary changes which took effect before the 2010 general election, the Leeds East constituency has been composed of Swarcliffe, Cross Gates, Whinmoor, Seacroft, Gipton, Harehills, Killingbeck, Temple Newsam, Halton Moor, Halton, Whitkirk, Colton and Austhorpe.[59]

The Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) for Yorkshire and the Humber European Parliament constituency elected in the 2009 European Parliament election, were Godfrey Bloom (UK Independence Party), Andrew Brons (BNP), Timothy Kirkhope (Conservative), Linda McAvan (Labour), Edward McMillan-Scott (Liberal Democrat), and Diana Wallis (Liberal Democrat).[60]

Geography

The Swarcliffe housing estate is situated between the Seacroft, Whinmoor and Manston estates, and is bordered by the A64/York Road to the north, Barwick Road to the south, Cock Beck and Scholes to the east, and the A6120, Leeds Outer Ring Road to the west. The smaller Stanks estate is included in the Swarcliffe area. After the western part of the estate was built in the 1950s, Whinmoor estate was built to the east and north in the 1960s. After a boundary change, the southern part of Whinmoor (to the east of the original Swarcliffe estate) is now part of Swarcliffe.

The underlying rocks are coal measures towards the northern extremity of the Yorkshire coalfield containing shales, mudstones, sandstones and coal seams laid down in the Carboniferous period. The rock strata have a general dip towards the south and south-east.[61]

Great Swarcliffe Wood, formerly Great Swarcliffe Plantation, which borders Swarcliffe Avenue, Eastwood Gardens, Swarcliffe Drive and Eastwood Drive, contains an abundance of sycamore, oak and rowan trees, being approximately 260 yards (240 m) long, and 170 yards (160 m) wide.[62] The Little Swarcliffe Wood, formerly Little Swarcliffe Plantation, borders Swarcliffe Drive, but can be accessed via Swarcliffe Bank. It has a collection of European trees, including sycamore, oak, ash, elm and lime. It is approximately 138 yards (126 m) long, and 97 yards (89 m) wide. Although the woods can be crossed along desire pathways, there are no official public rights of way.[62] Fed by the Grimes Dike from the north of York Road, the Cock Beck runs in a southerly direction past Swarcliffe and Stanks' eastern borders, and joins the River Wharfe to the south of Tadcaster.[63]

Neighbouring districts

Climate

Although the climate in Swarcliffe is generally relatively moderate, in 2011 it was reported that extreme winds had damaged the roofs of several flats in the Lombardy House block on Southwood Close. Structural engineers were called to inspect the damage.[64]

| Climate data for Swarcliffe/Seacroft (2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

18 (64) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

14 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.7 (44.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41 (1.6) |

46 (1.8) |

40 (1.6) |

55 (2.2) |

43 (1.7) |

61 (2.4) |

46 (1.8) |

44 (1.7) |

55 (2.2) |

65 (2.6) |

62 (2.4) |

69 (2.7) |

627 (24.7) |

| Source: World Weather[65] | |||||||||||||

Demography

In 2009, the population of Swarcliffe and Stanks was 6,751, of which 4,544 were considered to be "hard-pressed", or experiencing financial difficulty.[1]

In the 2001 census Swarcliffe was recorded as having 4,819 Christians, 18 Sikhs, 17 Muslims, nine Buddhists, six Hindus and six Jews.[37] The census recorded the ethnicity of the inhabitants: 6,303 White British, forty-seven Irish, thirty-two mixed race Black Caribbean and White, three mixed race Black African and White, thirteen mixed race Asian and White, twelve Indian, eleven Pakistani, three Black Caribbean, eleven Black African, and seven Chinese.[37]

Elmet Towers in 2007, shortly before demolition

Elmet Towers in 2007, shortly before demolition Three-storey flats on Stanks Drive

Three-storey flats on Stanks Drive Stanks Lane South

Stanks Lane South Sherburn Court, the last of seven fifteen-storey high-rise blocks built in the 1960s

Sherburn Court, the last of seven fifteen-storey high-rise blocks built in the 1960s

Education

Swarcliffe School, on Swarcliffe Drive, was an infant (5 to 8-years-old) and junior school (8 to 11-years-old), but the junior section was demolished in the 2000s,[66] and the school renamed Swarcliffe Primary School and Nursery.[67][68] In the early 1960s, Oxfam made a colour film for its 21st anniversary about the pupils of Swarcliffe School, called Swarcliffe Junior School Presents Our Daily Bread, which featured pupils creating a stand for Leeds' Freedom From Hunger exhibition.[69]

In September 1964, St. Gregory's Catholic Primary School opened on Stanks Gardens to accommodate the overflow of children from St Theresa's Primary School in Cross Gates, which is 0.9 miles (1 km), to the south. In 1989, the school moved to the former St. Kevin's Secondary modern school premises on Barwick Road.[70] The school closed in 2008 and was demolished in late 2009. The old school became St Gregory's Youth & Adult Centre, offering adult education classes, older people's services, child care, a Youth Service, and the Swarcliffe Good Neighbours Scheme which was established in 1994.[37][71][72][NB 3] Grimes Dyke Primary School was built in the late 1960s in the north eastern part of Swarcliffe.[73] In a 2008 census, it was reported that 1,419 children lived in the Swarcliffe area.[37]

Swarcliffe Children's Centre is a privately owned day nursery, on Langbar Road (behind The Staging Post public house),[74] and the Tykes Pre-School Playgroup is situated in the St Gregory's Y & A Centre, Stank Gardens.[75]

Churches

St Luke's Church is in the parish of Seacroft and part of the Seacroft Team Ministry; a group of (Anglican) churches in Seacroft, Whinmoor and Swarcliffe.[76][77] The parish is in the Diocese of Ripon and Leeds.[78] Funds to build the church were provided by the Lilley family, who were connected with the Samuel Smith Brewery in Tadcaster. The church was designed by M. J. Farmer and built in 1963, with stone taken from Ripon Cathedral being used to support the altar.[79] Swarcliffe Baptist Church opposite Swarcliffe Primary School and Nursery, was used as a classroom when the school suffered from overcrowding.[80] Stanks Methodist Church was opened on 23 February 1869, by Primitive Methodists, but the building was closed and the congregation disbanded in 2007.[81][82]

St. Gregory's Roman Catholic Church (Swarcliffe Drive, opposite Southwood Gate), formally called St. Gregory the Great Church,[83][84] is in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Leeds.[83] The land on which it stands was bought in 1954, but before building work started, mass was held in the priest's council house, with confessions taken through the dining hatch of the kitchen.[79] The first church on the site, a simple red brick hall opened on 11 October 1956, is now occupied by St Gregory's Social Club. On 12 March 1970, an octagonal church of modern design, by A. G. Pritchard Son & Partners, was opened next to the original church. It has simple bench seating for 335 worshippers.[79] St Gregory's Social Club hosts meetings of the Swarcliffe and Stanks' Residents and Tenants' Association.[57][85]

St Gregory's Church

St Gregory's Church St Luke's Church (closed 2012)

St Luke's Church (closed 2012) Swarcliffe Baptist Church

Swarcliffe Baptist Church

Shops and public houses

Swarcliffe Parade once had two rows of shops, but the north row was demolished in 2002.[86] As of 2011, the remaining parade consists of a Chinese takeaway,[87] a newsagent and off-licence,[88] a minimarket,[89] a bakery, and a betting shop.[90] As of 2011, Stanks Parade has a newsagent, a fish-and-chip shop and a unisex hairdresser.[91] A parade of shops and a post office on Langbar Gardens was closed in 2004.[92]

The Squinting Cat public house, once known as the John Smeaton after the 18th-century civil engineer from nearby Austhorpe.[93][94] The Whinmoor public house was closed in December 2010, and re-opened three years (2012) later as a pub, but also offers self-defence classes for ages of all which is placed on the left hand side of the building.[95] Swarcliffe Working Men's Club, a members only club, was built in the 1960s, in 2011 it had 1,700 members.[96] St. Gregory's Social Club was next to St. Gregory's Roman Catholic Church and was closed in 2011.[97] The Staging Post public house is on Swarcliffe Avenue/Whinmoor Way.[98]

Transport and infrastructure

Public transport in Swarcliffe is coordinated by West Yorkshire Metro.[99] The nearest rail station is Cross Gates station. Bus links from Swarcliffe to other areas are operated by First Leeds.[100][101] The nearest international airport is Leeds Bradford Airport, which is 12.4 miles (20 km) away.[102]

Built in 1973, Stanks Fire Station is on Sherburn Road. Under the control of the West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service, its 24 firefighters provide a service to more than 42,452 people, covering approximately 14.39 miles (23 km).[103] Policing is provided by West Yorkshire Police, operating from Killingbeck police station.[104] There are currently no dentists' practices or doctors' surgeries in the Swarcliffe area, although the Windmill Health Centre is just outside the north-west boundary, on Mill Green View,[57] and the Seacroft Dental Practice is on York Road, Seacroft.[105] Swarcliffe library on Langbar Road was recently closed; it will be replaced with a mobile library.[106][107]

Leeds City Council is responsible for providing all statutory local authority services in the area. These include: education, housing, planning, transport and highways, social services, libraries, leisure and recreation, waste collection, waste disposal, environmental health and revenue collection.[108] Yorkshire Water manages the area's drinking and waste water.[109] Northern Gas Networks distributes gas,[110] and CE Electric UK distributes electricity from the national transmission system to customers in Yorkshire.[111]

Media

As well as national newspapers, Swarcliffe is served by the daily Yorkshire Post, and an evening paper, the Yorkshire Evening Post (YEP). The Leeds Weekly News is a free publication, also produced by Yorkshire Post Newspapers in four geographic versions, which is distributed to households in the main urban areas of the city.[112] Seacroft Today is an internet site, funded by the Yorkshire Evening Post, which features news specifically about Seacroft, Whinmoor and Swarcliffe.[113] Local radio stations are BBC Radio Leeds,[114] 96.3 Radio Aire,[115] Magic 828,[116] Capital Yorkshire,[117] and East Leeds FM, which was started in 2003, by students from John Smeaton Community College in neighbouring Manston.[118] BBC Television and ITV have regional studios that serve the area.[119][120]

Inhabitants

In 2005, Norman Harding, a trade unionist, tenants’ leader and socialist, published Staying Red: Why I Remain a Socialist,[121] detailing his life and political activities while living at 40 Eastwood Crescent.[122] In 2008, he was writing book about Doris Storey, the winner of two Olympic swimming gold medals at the 1938 British Empire Games in Sydney, Australia. Mr. Harding lived in the Swarcliffe area, until his death in December, 2013.[123] The Leeds-born musician, Andrew Edge, grew up in the area, attending Swarcliffe School. He used two photographs taken in Swarcliffe, of a sunrise and sunset, for his Northern Sky album in 1996 (BMG Austria).[124]

Swarcliffe residents take part in the annual Leeds in Bloom Private Gardens competition, with a number of gold, silver or bronze winners living in the area.[125][126]

Crime

Crime rate data is collected by the Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnership; an organisation involving the local police force, council, fire authority, and primary care trusts.[127][128]

An example of anti-social behaviour which prompted the enforcement of an Anti-Social Behaviour Order, ASBO, was the case of a young man who, in 2008, had posted more than eighty videos of his anti-social behaviour on YouTube, including high-speed road races, verbal abuse, trespassing, leaving a petrol station (supposedly), without paying for petrol, and videoing his use of class A drugs. He was branded "Leeds' dumbest criminal" by councillor Les Carter, who added: "In the last three years, we have seen a 32 per cent reduction in crime in Leeds. If more criminals were as obliging, the city would be even safer".[129]

In 2010, a Chinese national, who led a gang of smugglers, was jailed for over three years for running an operation worth £1.5 million. The cargoes of cigarettes and alcohol were hidden in shipments of tea, plastic bags and storage shelves.[130] In 2011, a 42-year-old female drug dealer was jailed for six years for paying others up to £5,000 to confess to her crimes.[131] drugs took over swarcliffe in the late 90s and local teens would steal cars and put shows on outside the post shops a red Ferrari 355 spider taken from a house burglary in North Leeds was just one of the cars took by a gang of teens called swc boys

Footnotes

- In 1997, Alan Noble, the church warden of St James’ Church, Seacroft, remembered moving to a tied cottage in Taylors Yard in 1926, when his father was employed by Mr. Presious; the owner of Swarcliffe Farm. From: Memories of Seacroft as a Village 1926 to 1947, a pamphlet by Alan Noble. Published by Seacroft St James' PCC. 1998

- A small part of the Swarcliffe estate in the north-east is now within Seacroft

- In 2010, 600 people signed a petition to prevent the closure of the centre.

References

- "2009 Population ACORN Profile" (PDF). CACI. 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Campbell 1995, p. 8.

- "Anglo-Saxon West Yorkshire: The historical background". West Yorkshire Joint Services. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Marsden, Richard. "The Battle of Winwaed – Location". Winwaed. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Gilleghan, John. "A Brief History of Seacroft". Seacroft Parish. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Battle of Seacroft Moor – 30 March 1643". UK Battlefields resource Centre. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Hinson, Colin (29 May 2011). "The Ancient Parish of Barwick-in-Elmet". Genuki. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- "Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913 + 1828)". The ARTFL Project. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Veitch, W; Veitch, R. A. (1910). The Scottish law reporter. The Law Reporter. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Aitchison, K. "A Brief History". A. S. Cowper & The Corstorphine Trust. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Swarcliffe/Seacroft/Stanks maps from 1849 to 1991)". old-maps. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "List of Turnpike Trusts". Turnpikes.org. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Alan Noble (1997–1998). "Memories of Seacroft as a Village 1926–1947". The Seacroft Village Preservation Society(originally in Seacroft Herald). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- The statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Volumes 32–33. Great Britain. 1840. p. 708. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Thoresby, Ralph. "Ralph Thoresby's Journey to Barwick – 1702". The Barwicker No.51. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Hull, Brian. "The Gascoigne Mines in Garforth". Parlington Hall Website. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- Colman, F. S. (1908). "A History of the Parish of Barwick-in-Elmet in the County of York". Barwick-in-Elmet Historical Society. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Welcome to the Britannia Leeds hotel". Britannia Hotels. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Seacroft History". Leeds Today. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Isaac Chippindale & Sons, brick and tile manufacturers". The National Archives. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- Marshall, Nigel. "The Chippindale Family". pro-patria-mori. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- "Leeds to Wetherby". Lost Railways West Yorkshire. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Cox, Tony. "The Leeds – Cross Gates – Wetherby Railway". Barwick-in-Elmet Historical Society. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- "The Development Of The Major Railway Trunk Routes". Railways Archive. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Appendix to the twenty-sixth (twenty-seventh, thirty-fifth-forty-seventh) report. Ecclesiastical Commissioners. 1874. p. 327. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Seacroft Hall, view across the lake". Leodis. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Darcy Bruce Wilson (1851–1936)". Who begat Whom. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Transactions of the Newcomen Society". The Newcomen Society for the Study of the History of Engineering and Technology. Newcomen Society. 19: 103. 1940. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Seacroft Hall, view across the lake". Leodis. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- "Parklands Girls' High School". Find My School. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- The Civil engineer, Volume 7. The Civil Engineer. 1953. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- The electrical review, Volume 157, Issues 1–9. The Electrical Review. 1955. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "The Scholes Villages". Scholes’ Family. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Bell, Chris. "LS14 5 postcodes, Leeds". Doogal. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "1979: Council tenants will have 'right to buy'". BBC. 3 October 1980. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "The Sale of Council Houses (Conservative Party Manifesto)". Political Resources. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Leeds Neighbourhood Index" (PDF). Leeds City Council. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Household Demographics (Swarcliffe)" (PDF). Leeds City Council. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Historic England. "Elmett Towers (1507684)". PastScape. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Glendinning, Miles. "Tower Block". Fields. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Building Control – Building Control Summary". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Woodview, Leeds". Anchor Trust. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Estate will replace tower flats". Yorkshire Evening Post. 24 June 2005. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Wellington Hill, Whinmoor and Red Hall" (PDF). Leeds City Council. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Historic England. "Sherburn Croft (1507775)". PastScape. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- "No. of entries in Leeds: 201". Skyscraper News. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Williamson, Howard (27 July 2006). "Work starts on £113m revamp of estate". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Leeds tower block's new lease of life". Yorkshire Evening Post. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Harris, Mark (29 July 2011). "£100m investment for Swarcliffe homes". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Jones et al. 2007, p. 190.

- "Swarcliffe Housing Project". Yorkshire Transformation. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "St. Gregory's". Persimmon Homes. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Council and democracy – Suzi Armitage". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Council and democracy – Peter Gruen". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Council and democracy – Pauleen Grahame". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Grahame, Pauleen. "Register of interests". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- "Local Area Information" (PDF). avh Leeds. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Local Election Results May 2011: Crossgates and Whinmoor". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Rayment, Leigh. "The House of Commons Constituencies beginning with "L"". Leigh Rayment. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Your Members of the European Parliament". Write to Them. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "Leeds Geological Association: local geology". 2009. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Great and Little Swarcliffe Woods". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Policy Statement on Flood Defence" (Pdf). Leeds City Council. p. 5. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "High winds damage roof of Swarcliffe flats". BBC. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Climate info for Swarcliffe" World Weather, 30 July 2011, web: worldweatheronline.com.

- "Swarcliffe Primary School". Leodis. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Swarcliffe Primary School and Nursery". Swarcliffe Primary. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Murphy, L (5 May 2005). "Inspection Report: Swarcliffe Primary School and Nursery" (PDF). Ofsted. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- "Video: Hunt for stars of 1960s Leeds school film". Yorkshire Evening Post. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "History of the Parish". St. Theresa's Church, Cross Gates, Leeds. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Swarcliffe Good Neighbours Scheme". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Welcome To The SGNS Website". sgns. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Grimes Dyke Primary School". Grimes Dyke Primary School. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Swarcliffe Children's Centre". Day Nurseries. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- "Tykes Pre-School Playgroup". Education Vacancies Ltd. 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- "The Seacroft Team Ministry". WordPress. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- "Swarcliffe: St Luke, Swarcliffe". A church near you. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "Parish of Seacroft Team Ministry". Diocese of Ripon and Leeds. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Minnis, John. "Religion and Place in Leeds" (PDF). English Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Welcome to the Swarcliffe Baptist Church, Leeds web site". Swarcliffe Baptist Church. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Spring Synod 2007 Agenda". Methodist Church – Leeds District. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Bantoft, Arthur. "Stanks Methodist Church". Barwick-in-Elmet Historical Society. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "St. Gregory The Great". Diocese of Leeds. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "St. Gregory's Roman Catholic Church". Genuki. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Thorpe, Peter (30 September 2003). "Fighting back". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Swarcliffe Parade, Swarcliffe". Leodis. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Tung Ying". Just-Eat. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Dawson, Jayne (17 February 2006). "A superstar is born". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Food King Superstores". Leeds Online. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Property History". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Jamnian Wool". 118. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Marsh, David (29 December 2004). "'Save our shops' beg estate residents". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Capital Receipts – Sites scheduled for disposal 2008/09 to 2012/13". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Calls for problem Leeds pub to be torn down". Yorkshire Evening Post.

- "Long Leasehold Public House For Sale". NovaLoca. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Swarcliffe WMC". Swarcliffe WMC. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "St. Gregory's Social Club". Yell. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Staging Post, Whinmoor". UseYourLocal Ltd. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Metro. Here to get you there". West Yorkshire Metro. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Welcome to First in Leeds". FirstGroup plc. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Travel For West Yorkshire". Travel For. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Leeds Bradford International Airport". Leeds Bradford International Airport Company. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Stanks (Fire Station)". West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "West Yorkshire Police ::: Neighbourhood Policing :::". 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "Seacroft Dental Practice". Yellow Pages. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Leeds City Council to close 13 libraries". BBC. 19 May 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Swarcliffe Library, Langbar Road". Leodis. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Leeds City Council". 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "In your area". 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Delivering gas to the North of England". Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- "CE Electric UK". Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- "Leeds Weekly News". British Newspapers Online. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Seacroft Today". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Radio Leeds". BBC. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "96.3 Radio Aire". 96.3 Radio Aire. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Magic 828". Magic 828. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "105 Capital FM". Capital Yorkshire. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "elfm". East Leeds FM. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Look North". BBC. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Yorkshire Regional News: Calendar". ITV (Yorkshire). Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- Harding, Norman. "Staying Red: why I remain a socialist". Index Books. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Harding 2005, pp. 274–280.

- "Leeds swimming gold medallist subject of book". Yorkshire Evening Post. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Northern Sky (1996), by Andrew Edge. CD liner notes. Record company: BMG Records, Austria. Album bar code: 4321-37102-2.

- "Leeds in Bloom private gardens competition". Leeds City Council. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Results of Leeds In Bloom Gardens Competition 2010" (PDF). Leeds City Council. 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Leeds LS14 crime statistics". The Digital Property Group Limited. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Welcome to the Whinmoor, Swarcliffe and Stanks Neighbourhood page". West Yorkshire Police. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Britain's 'dumbest criminal' is banned from boasting about his offences on the internet". Daily Mail. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Leeds cigarette smuggler jailed". Yorkshire Evening Post. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Gardner, Tony (14 April 2011). "Leeds drugs bribe mum jailed". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

Bibliography

- Campbell, James (1995). Essays in Anglo-Saxon History. Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-0-907628-33-0.

- Jones, Phil; Moss, Dorothy; Tomlinson, Pat; Welch, Sue (2007). Childhood: services and provision for children. Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-3257-1.

- Harding, Norman (2005). Staying Red: Why I Remain a Socialist. Index Books. ISBN 978-1-871518-25-2.

- The Municipal Journal, Volume 70, Issues 3594–3606. Great Britain, Ministry of Housing and Local Government. 1962.

- Smith, Albert Hugh (1961). The Place-names of the West Riding of Yorkshire: Lower & Upper Strafforth and Staincross wapentakes. The University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swarcliffe. |